I’ve been sick with Covid this past week after eluding it for three years. I felt like I was a fugitive in hiding, living in the shadows (with a mask on), but then Covid caught me, as if I was just an anonymous character in a horror movie.

This was a serious matter because I have a condition that puts me in a higher-risk group, but once I realized the throes of Covid weren’t going to kill me, I sunk into it.

The fact is I secretly covet being sick. This is strange, I know, but illness is the rare life event that can cause life to stop, which is a gift. Illness brings me closer to myself in mysterious ways. It declutters my mind. It melts my arrogance. It waters my humility. Suddenly, I can focus all of my attention on the essentials: trying to be well.

Even a vacation doesn’t stop life in such a way because the me that makes me, me tends to march on. It’s hard to make the rhythm of my marching stop.

But sickness has a beautiful way of wreaking havoc with my body while returning me to my soul. It’s a type of drug (which makes it especially appealing to me as one who no longer imbibes). It’s a creative elixir. When I’m ill, I often feel as if I’m a seer. I gain access to a whole new terra incognita of the mind.

It’s interesting to me that illness is often portrayed as being unnatural—that we have to bounce back to “be ourselves again.” The irony is that as I recovered, part of me wanted to stay sick because I felt more myself in that solitary hovel of illness, and I was afraid the real world would take that away. Being out of sorts was preferable to being in sorts (because being “in sorts” in my normal “health” sometimes feels so out of sorts).

So I’ve decided to celebrate sickness in this week’s newsletter, to explore all that sickness can give our art and our being.

I thought about how in the 19th century, tuberculosis was considered a disease of passion, of “inward burning,” of the “consumption” of life force. Sufferers were thought to have superior sensibility. The illness purified them of the dross of everyday life.

I feel such purification when I’m sick. In the wrenching possession of a fever, the violence of a virus, I’m transformed into a supplicant, more humble, more grateful, more connected to others. Somehow the universe opens even as it closes.

In Virginia Woolf’s amazing essay “On Being Ill,” she puts it perfectly:

“Considering how common illness is, how tremendous the spiritual change it brings, how astonishing, when the lights of health go down, the undiscovered countries that are then disclosed, what wastes and deserts of the soul a slight attack of influenza brings to view, what precipices and lawns sprinkled with bright flowers a little rise of temperature reveals, what ancient and obdurate oaks are uprooted in us by the act of sickness … it is strange indeed that illness has not taken its place with love and battle and jealousy among the prime themes of literature.”

In health, Woolf argues, we live in an illusion of being cradled in the arms of a caring world. Illness jostles us out of such an illusion, but it also awakens us to the world about us, and previously unnoticed details suddenly throb with life.

We need illness to twist our minds out of their ruts.

I’m interested in this because in realizing the coldness of nature, I strangely feel a deeper belonging —a belonging of self that is rediscovered and is much stronger and truer than the flimsy, scattered, and perhaps reckless sense of belonging I generally live with.

Woolf gets at this sense of belonging when she says illness renders us “able, perhaps for the first time for years, to look round, to look up—to look, for example, at the sky.”

The first impression of that extraordinary spectacle is strangely overcoming. Ordinarily to look at the sky for any length of time is impossible. Pedestrians would be impeded and disconcerted by a public sky-gazer. What snatches we get of it are mutilated by chimneys and churches, serve as a background for man, signify wet weather or fine, daub windows gold, and, filling in the branches, complete the pathos of dishevelled autumnal plane trees in autumnal squares. Now, lying recumbent, staring straight up, the sky is discovered to be something so different from this that really it is a little shocking. This then has been going on all the time without our knowing it! — this incessant making up of shapes and casting them down, this buffeting of clouds together, and drawing vast trains of ships and waggons from North to South, this incessant ringing up and down of curtains of light and shade, this interminable experiment with gold shafts and blue shadows, with veiling the sun and unveiling it, with making rock ramparts and wafting them away…

In celebrating, relishing, and even indulging in sickness, a whole new way of being emerges.

I’ve never liked most of our common metaphors for healing. Illness is often presented as something to fight. A patient must soldier on. An illness is an endurance test, a marathon. Doctors “search for silver bullets” and “use all weapons at our disposal.”

But what if instead of fighting, we accept illness? What if we lay down with illness as if laying down with a lover? I have always liked succumbing to an illness, to let it have its way with me, to sink into its tender touches. And even its not so tender touches.

I read that patients who view their disease as an enemy tend to have higher levels of depression and anxiety than those who give it a more positive meaning.

We need illness to coax our minds out of their ruts. We need to revere it for all of the mysterious things it has to give. Somehow, one of those things is life. Or the recognition of life.

Because a quote

“Illness is the night-side of life, a more onerous citizenship. Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick.”

—Susan Sontag

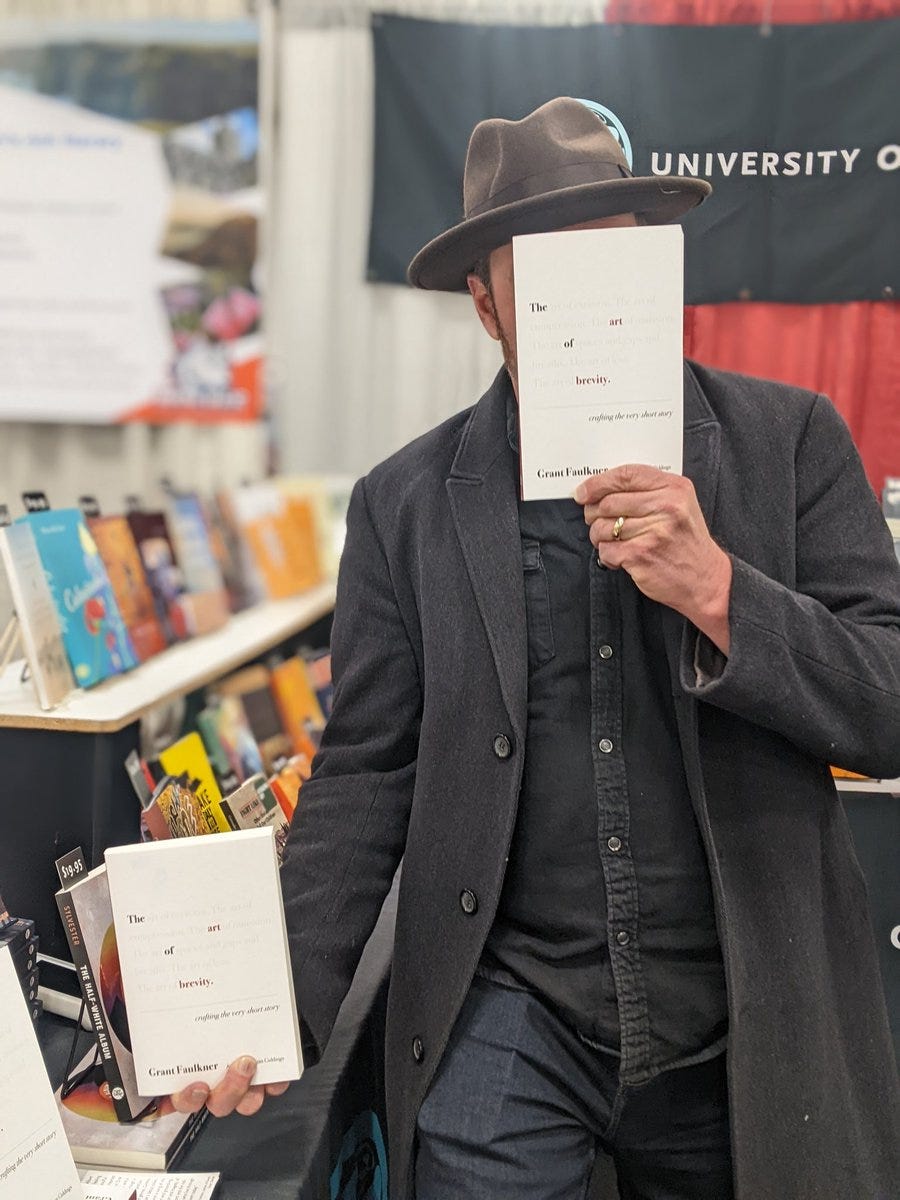

Because I like talking at book festivals

The Bay Area Book Festival is coming up next week, May 6-7, and it’s one of my favorite book festivals because I can literally walk to it. There are also all sorts of wonderful writers involved.

I’m taking part in two events:

The Art of Brevity: A Flash Fiction Writing Workshop

Saturday, May 6 | 11:00 AM - 11:45 AM

NaNoWriMo executive director Grant Faulkner (author of The Art of Brevity) and author and educator Kim Culbertson (author of the forthcoming Small, Bright Things: 100-Word Stories in the ELA Classroom) will combine their expertise with your inspiration in a fast-paced, low-pressure generative flash fiction workshop perfect for teens and adults.

Saturday, May 6 | 2:30 PM - 3:30 PM

We’re fortunate that several contributors to the new anthology Flash Fiction America: 73 Very Short Stories hail from right here in the Bay Area—and we’ve brought them together for a big celebration of small stories. Patricia Quintana Bidar, K-Ming Chang, Grant Faulkner, Molly Giles, Nicole Simonsen, and Kara Vernor will read their stories reading and talk about what it takes to write fantastic flash fiction.

Because The Art of Brevity

Please consider buying my new book, The Art of Brevity. Writers tell me they like it. You might say it’s my way of being a poet in this world. My little stories are my little prayers. I like to drop them into the world.

Because more about me

I am the executive director of National Novel Writing Month, the co-founder of 100 Word Story, and an Executive Producer of the upcoming TV show America’s Next Great Author. I am the author of a bunch of books and the co-host of the podcast Write-minded.

My essays on creative writing have appeared in The New York Times, Poets & Writers, Lit Hub, Writer’s Digest, and The Writer.

For more, go to grantfaulkner.com, or follow me on Twitter or Instagram.

I can’t stress enough what a strange experience the timing of this particular newsletter is, as I got to reading it while going into my second night of being hospitalized for an infection in a chronic wound I’ve been dealing with. As always, you seem to have just the right words Grant. I hope you’re feeling better, but am so glad that in your illness you were able to offer such words of inspiration and find for yourself such an important time of introspection. I’m definitely going to do some of my own journaling on thoughts this stirred up before getting some rest.

This makes me want to take to my bed with faintness and palpitations. I haven’t been sick since well before Covid, and you’ve made me wonder if my persistent good health (injuries aside, like an equally persistent tendinitis) is at least partly to blame for my sense of ennui, which I’ve blamed on the state of the world. Though I do know that feeling of relief when, say, a sore throat keeps me at home and disrupts plans I both want and don’t want to keep. Thank you for the glorious words of Woolf and for your honesty and self-awareness. I’d say I’m sorry you’re sick, but instead I’ll wish you the most you can get from ol’ Covid.