“When you're a bed wetter there's only one group of people you can feel better than, bed shitters, and unfortunately they're hard to come by.”

— Sarah Silverman

Dear Readers,

I recently read a review of Sarah Silverman’s new musical comedy, The Bedwetter, which is based on her memoir of the same name. It made me think two things: 1) we’ve come a long way since Hemingway criticized F. Scott Fitzgerald for whining in public in his series of confessional essays about his mental breakdown (later collected in The Crack-Up); and 2) the best art explores (and risks) shame.

It also made me think of my own early life as a bedwetter.

Wetting the bed was my first mark of shame. My early childhood was strewn with pee-soaked sheets stuffed into closets, pajamas hastily taken off and hidden, the feeling of waking up in a sop. Being a bedwetter was the first thing that made me realize my self didn’t exactly fit in the world—that I had a self that did messy, wrong things just by being alive.

I remember one morning, after waking up in a puddle, walking down the hallway to tell my father that I’d wet the bed again (yet again), and he erupted in anger, exasperated, as if I’d done it intentionally.

That must have been the last time I told anyone I’d wet the bed. It was as if I crossed over from one phase of childhood—the one where you trust in others to take care of you—to another—the one where you hide your transgressions. Why aren’t there names for these phases?

The mark of shame makes you adept at hiding. You are alone. My brother and sister didn’t wet the bed. None of my friends wet the bed. Being a bed wetter was my own private club. It was my blemish, and it was a blemish I knew I had to cover up.

But bed wetting is a particularly challenging thing to hide. A simple sleepover wasn’t a night of rollicking fun for me as it was for others; it was always a night of terror, a gamble with all of the dark forces of the night. No matter how much I fought sleep, I’d eventually drift off, and once I fell asleep, the bed-wetting monster entered the room and punished me … just for being human.

As Silverman put it, “The word ‘sleepover’ to a six-year-old bedwetter has roughly the same impact of, say, ‘liver cancer’ to a 40-year-old alcoholic. The moment the word is spoken, gruesome images of your near future flood your mind. At least with liver cancer, people gather at your bedside instead of run from it.”

My bed wetting got bad enough, and I got old enough, that eventually, my mom took me to see the doctor. He didn’t have any answers, of course. He told her to make sure I didn’t drink liquids before bed. He told her that if things continued, there was a new machine I could possibly use. It would somehow detect when I was going to pee, and then it would wake me up.

I didn’t really want such a machine, though. Even then, I knew that my bed wetting might be a sign of a strange strength. I simply slept more deeply. I let the world of dreams take me away. I was unconsciously less observant of the boundaries between dream and reality. I didn’t like boundaries in general.

As much as I carried shame and worry with me in those years, I now realize that I learned something from it all: I became adept at knowing that shame wouldn’t kill me. I realized the skills required to live a secret life. And as I got older, I realized I wasn’t alone: the world was full of bedwetters of all sorts. We are all creatures of shame.

I also realized that my immersion in my dream life had little place in reality. In fact, my dreaminess was likely to create a mess in the real world. There’s truth in this, even now.

Art is fundamentally an act of exposure. An artist opens closets, dares to go into dark basements, and rummages through the attics of their souls. That’s our duty, our gift.

So Hemingway was wrong. What he called whining was actually a brave confession. Fitzgerald’s dark night of the soul was all that we want from writing. Because none of us want to feel so lonely in our private club.

Because a quote

“I talk with the authority of failure.”

― F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Crack-Up

Because a haiku

stars bite through the darkness— summer's first day

Because a meditation

Every once in a while, I like to pause and look at the details of Hieronymus Bosch's The Garden of Earthly Delights. I remember how completely overwhelmed I was the first time I encountered it as a teenager. I thought Bosch captured humanity’s desires and deepest fears better than anyone I’d ever known. It’s still so arresting after all of these years. Somewhere in it, there’s a bedwetter, I’m sure.

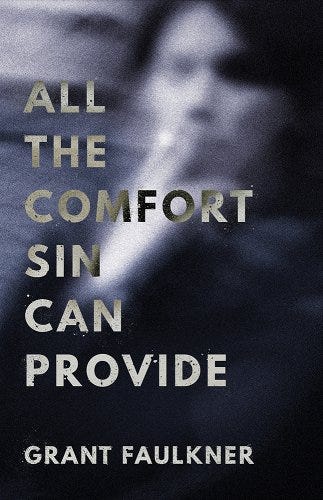

All the Comfort Sin Can Provide

If you like this newsletter, please consider checking out my recently released collection of short stories, All the Comfort Sin Can Provide.

Lidia Yuknavitch said:

“Somewhere between sinister and gleeful the characters in Grant Faulkner’s story collection All the Comfort Sin Can Provide blow open pleasure—guilty pleasure, unapologetic pleasure, accidental pleasure, repressed pleasure.”

Grant Faulkner is executive director of National Novel Writing Month and the co-founder of 100 Word Story. He’s the author of Pep Talks for Writers: 52 Insights and Actions to Boost Your Creative Mojo and the co-host of the podcast Write-minded. His essays on creative writing have appeared in The New York Times, Poets & Writers, Lit Hub, Writer’s Digest, and The Writer.

For more, go to grantfaulkner.com, or follow him on Twitter at @grantfaulkner.

Open up about a demon and we all want to hear about it. And this one is especially virulent because of its impact on young souls. I felt your pain. I felt your shame. I felt your helplessness. But I also saw your growth and adaptation and how you transformed a secret into art. Good job my friend.