Last week, I rode a horse for the first time in ten years. It was interesting because I didn’t count on the experience to illuminate anything about art or living. I thought it would just be fun and nothing more. But it was more.

As a kid, I was infatuated with horses. I suppose it was watching Westerns as a boy, the way the horse and rider were connected in both flesh and spirit. Horses held a majesty, an entrancing dignity.

I begged for a horse. I collected horse figurines. I went to horseback riding camp. Finally, my parents bought me a horse for all of $125. Ginger. A beautiful brown quarter horse.

We found a nearby pasture for Ginger, and I rode her occasionally, but I was only 12, and I was intimidated by her size, and then a fellow classmate had been kicked in the head by a horse and permanently disabled, so I didn’t ride her often. Eventually, she went to my grandparents’ farm, where she was unfortunately struck by lightning in a pasture.

I rode occasionally over the years, but mainly rental horses, which were expensive and not much fun. How much fun can you have walking in a line with other horses at a ploddingly slow pace, nose to butt?

Last Sunday, I got the opportunity to ride a horse, and not only ride, but ride on Jack London’s former ranch in Glen Ellen. My horse was named Buzz, and he was a beautiful white horse with brown spots.

At first, I thought we were just going to meander along the trails at a slow pace, like the rentals I’d been on, but Chuck, the owner of the horses and my riding partner, wanted to go faster.

First, we trotted. That was manageable (if bumpy). It was interesting to feel Buzz’s muscularity, the pure force he held, and how, if unbridled, if running loose, how scary he’d be.

Then we moved into a canter—less bumpy, but faster. As I swayed in the saddle to the rhythms of Buzz’s strides, gripping the reins and at the ready to pull back in case he got out of hand, I realized the tenuous nature of my “control.” No matter Buzz’s training or my horsemanship (which was lacking), I was at the mercy of Buzz. At the mercy of the world. A gust of wind, a loud noise, or another animal could spook him, after all.

Fortunately not, though. Buzz was nice enough not to test me in any way. He took me for a ride more than I took him for a ride.

I later thought about how I was both “with” and “at the mercy of” Buzz. I had to trust him at the same time I had to watch him. I had to trust myself at the same time I had to watch myself.

We were careening, yet we were in control. That’s perhaps the definition of a peak moment. It’s also the definition of creation at its best: you don’t quite know where you’re going, what forces are at work, or whether those forces are dangerous or safe, but you’re directing things—and surrendering to them.

Because it’s better without a rope until you fall

I recently watched the movie The Alpinist, which is about a charming, free-spirited 23-year-old climber, Marc-André Leclerc, and the solo ascents he makes up icy mountains—out of the limelight, just for his own spiritual adventure, which is part of the intrigue of the film.

The film is reminiscent of Free Solo, the Oscar-winning documentary about Alex Honnold’s attempt to become the first person to ever free solo climb El Capitan. All of these movies are essentially the same. A guy climbs increasingly high and more dangerous mountains. His friends and family are in awe of him, yet afraid for his life. The filmmakers show others who have died young. There’s the haunting question, “Why do they do this? Why do they risk their young, beautiful, bold lives?”

I suppose the same question can be applied to many artists, or to any who are obsessed by a single pursuit that feels like all of life matters because of it.

In The Alpinist, Alex Honnold makes an interesting observation about the difference between him and Leclerc. He says that even when climbing El Capitan without ropes, he felt in control to a large degree because he was climbing on solid rock, but Leclerc, by climbing on ice, is at the mercy of it breaking or at the mercy of an avalanche.

He’s careening. But he’s confident (and perhaps arrogant enough) to trust he’s in control. But he’s careening.

Why do these guys climb in spite of the high odds they’ll die? Because living on that precipice might be the best kind of life. Or it’s just the kind of life they have to live. I don’t know if much choice is involved.

I was especially fascinated by one irony Leclerc pondered. He said he’s never changed as much as he thinks he’ll be after reaching a new height. He returns to an ordinary life with the glow of achievement, but nothing much has changed. He still feels himself as the same person he was before the climb; he still feels his ordinary life.

I feel the same after finishing a book or any creative work. No matter the urgency, pressure, or madness I felt in the making of it, once I complete it, there’s a troubling anticlimax. I’m not sure what the value of the pursuit was. But I know I’ll do it all over again. Because I need “the climb.”

It’s about believing that it matters. A life of believing that it matters is just better.

Because a haiku

The sparrow throws its head back too sure of itself the cat says

Because a quote

“Poetry has no investment in anything besides openness. It's not arguing a point. It's creating an environment.”

~ Claudia Rankine

Because a beautiful story

K-Ming Chang’s Footnotes on a Love Story is a story that is told like a normal story, except unlike most short stories, it comes with footnotes, as if it’s an academic work. The footnotes ask how it should be read because so much of the story is in the footnotes. Do you pause to read the footnotes as you read the story, or do you come back to read the footnotes, or do you not read the footnotes at all, because footnotes always seem to invite you to pass over them, to get by with only knowing one part of the story, except sometimes footnotes present a world that seems bigger and more important than the story they’re commenting on.

So the questions of the story: what is the story, whose story is it, how do stories intermingle, what can be overlooked, and what does it mean to overlook part of the story?

It’s a wonderful story about love. Especially if you read the footnotes.

Because whimsicality

Pamplemousse. One of my all-time favorite words. So I was so happy to discover the band, whimsically named Pomplemoose.

Listen to Pamplemoose! Guaranteed happiness.

Because prompts take us to new places

Use this photo as a prompt, as a random catalyst, as an igniter for any writing project you're working on.

Or … write a story about this photo in less than 300 words.

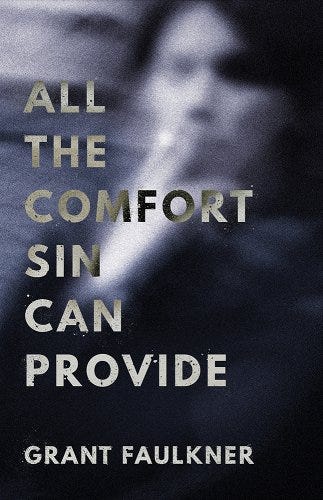

All the Comfort Sin Can Provide

If you like this newsletter, please consider checking out my recently released collection of short stories, All the Comfort Sin Can Provide.

Lidia Yuknavitch said:

“Somewhere between sinister and gleeful the characters in Grant Faulkner’s story collection All the Comfort Sin Can Provide blow open pleasure—guilty pleasure, unapologetic pleasure, accidental pleasure, repressed pleasure.”

Grant Faulkner is executive director of National Novel Writing Month and the co-founder of 100 Word Story. He’s the author of Pep Talks for Writers: 52 Insights and Actions to Boost Your Creative Mojo and the co-host of the podcast Write-minded. His essays on creative writing have appeared in The New York Times, Poets & Writers, Lit Hub, Writer’s Digest, and The Writer.

For more, go to grantfaulkner.com, or follow him on Twitter at @grantfaulkner.

I'm still thinking about poor Ginger struck by lightning! Metaphor there somewhere?

Also, about the troubling anticlimax to finished writing, is there some extended fulfillment or gratification with the reactions of readers to that writing?

I love the way you break up the post and add diverse elements each week. Trust and surrender are perennial topics worth deep exploration, and sharing your perspective is inspiring, Grant. Thank you!