I’m not sure if satisfaction should be a life goal. Or I’m not sure if it can be for me.

Definitions of satisfaction include “a state of being pleased, proud, happy, and content”—good stuff, but then there’s the shadow side of satisfaction: satisfaction can also mean “a state of being smug, pleased with oneself, complacent, settling for.”

I’ve been thinking about how moments of satisfaction, as pleasing as they are, are fleeting by definition, but maybe that’s a good thing. The best work that humans produce in any field is molded by our dissatisfactions (another word for seeking, you might say), not our satisfactions. We are creatures of dissatisfaction, which is why we’re creatures of creativity.

Martha Graham put it best: “No artist is pleased. There is no satisfaction whatever at any time. There is only a queer, divine dissatisfaction, a blessed unrest that keeps us marching and makes us more alive than the others.”

It is a discordant concept, to have a dissatisfaction that is divine in nature. This isn’t a dissatisfaction that is the result of typical artistic self-loathing or self-doubt. It is not a dissatisfaction created by a demanding perfectionism that aims to please others. Graham’s dissatisfaction is divine because it is the result of the artist’s drive to create something that reaches empyreal heights.

Faith in a religion or belief in God isn’t the issue here, but rather the notion of creating a work that is sublime. The sublime is a term in aesthetics that refers to the conjunction of two opposed feelings, the pleasurable anxiety we experience when confronting things that inspire awe: “a feeling of respect or reverence mixed with dread and wonder, often inspired by something majestic or powerful” (according to The American Heritage Dictionary)

Graham spoke of dance with such religiosity. She viewed the body as a “sacred garment” and dancers were “messengers of the gods.” In striving to create a sublime work, a work that is elevated, exalted, lofty, beyond the mediocrity of the human realm, Graham’s state of “blessed unrest” propels and animates the artist—attuning her to life in a way that others cannot be if they reside in the more slothful contentedness of satisfaction.

Dissatisfaction is a valuable resource. Dissatisfaction fuels action. Dissatisfaction becomes its own peculiar motivator. And more. It’s the lens you view your work through that makes you anything but complacent and smug. Dissatisfaction pulls and prods and pushes you deeper into your work, into yourself.

Any great passion implies imbalance, and it’s those who aren’t entirely at ease in this world who go off looking for something else, something better. Even as you might seek equilibrium. That’s the paradox. The artist seeks to bring equilibrium to the world through a demanding dissatisfaction.

When Dorothy Parker famously said, “I hate writing, I love having written,” the “hate” she felt was about the arduousness of addressing that dissatisfaction, of uncovering it, facing it, putting just the exact word for it.

Zadie Smith advises writers to “resign yourself to the lifelong sadness that comes from never being satisfied.” Perhaps “never” is an overstatement, for we need satisfaction to put our work, ourselves, into the world. Or maybe it’s that “divine dissatisfaction” leads to a different type of satisfaction.

Graham found her truest satisfaction in the assiduousness of practice, which for her was akin to religious observance. Practice meant “to perform, over and over again in the face of all obstacles, some act of vision, of faith, of desire” in an effort to overcome the primary sin she knew: mediocrity. For Graham, practice was “a means of inviting the perfection desired.”

This type of practice doesn’t serve to shape your work into a form that pleases others so that it will get published. This type of practice serves a higher calling, one that has no concerns with whether a work finds acceptance or leads to ostracization because it speaks to a more elevated, even sacred, truth.

“It is well to fly towards the light, even where there may be some fluttering and bruising of wings against the windowpanes, is it not?” Elizabeth Barret Browning wrote to Robert Browning in their epistolary courtship. She looked to her anguish to instruct her in her joy.

Dissatisfaction is a kissing cousin of critical thinking. It’s a trait that helps you scrutinize ideas, aesthetics, situations, and people in life. If you’re dissatisfied with the state of the world, or if you’re dissatisfied with yourself, you seek satisfaction through change. One goes on a quest for a self one will be satisfied with—so dissatisfaction sparks defiance, a revolt against the status quo.

In those raw edges of experience, art is born.

A quote on creating in a state of disequilibrium

“I find that many of my favorite lyrics are those that I do not fully understand. They seem to exist in a world of their own—in a place of potentiality, adjacent to meaning. The words feel authentic or true, but remain mysterious, as if a greater truth lies just beyond our understanding. I see this, not just within a song, but within life itself, where awe and wonder live in the tension between what we understand and what we do not understand.”

—Nick Cave

I’m teaching a free flash fiction workshop this week

Join me at a “Flash Fiction Master Class” hosted by Wayfaring Writers on Tuesday, August 23, at 5 p.m. Pacific Time. I’m going to give a preview of my upcoming book, The Art of Brevity, and then lead a discussion on flash fiction and do a writing exercise.

Afterward, there will be info about the Wayfaring Writers’ Oaxaca Writing Retreat this December, which I’ll be teaching at as well (so sign up for that if you can).

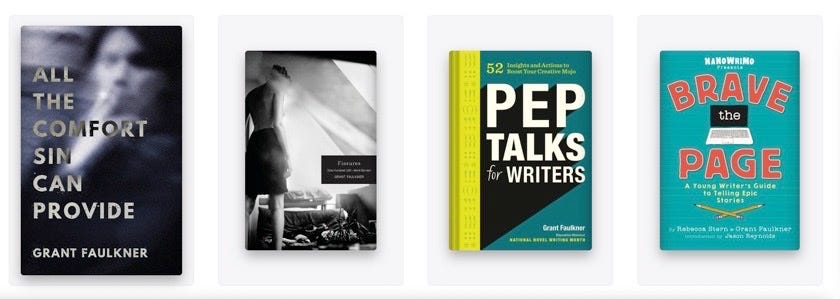

Because I’d love you to read one of my books

I write for many reasons, but mainly just for the joy of being read and having conversations with readers. This newsletter is free, and I want it to always be free, so the best way to support my work is to buy my books or hire me to speak.

Because more about me

I am the executive director of National Novel Writing Month, the co-founder of 100 Word Story, and an Executive Producer of the upcoming TV show America’s Next Great Author. I am also the author of a bunch of books and the co-host of the podcast Write-minded.

My essays on creative writing have appeared in The New York Times, Poets & Writers, Lit Hub, Writer’s Digest, and The Writer.

For more, go to grantfaulkner.com, or follow me on Twitter or Instagram.

That Martha Grahm quote is one of my FAVORITES. I think about it all the time, so when I saw the title of this newsletter, I was delighted to find the full quote included. So many gems of wisdom in this whole piece. Always enjoy these showing up in my inbox. ^_^

You convinced me in this piece. I want satisfaction in my life so much that when you pose the value of dis, it rubs me slightly off. But I think you're right. The lingering off-sync with life keeps us wanting to correct the rhythm and speak to the rhythm and find meaning on the off-synchness. (how's that for a word?) To put it spiritually, we are not home, this is not heaven, we are a fallen people, and art is all about feeling that separateness and railing against that disjointedness and making sense of the off-synchness. (there, twice!)

I cannot tell you how much I LOVE the Nick Cave quote! My exact sentiments.