I’m working on a new book, and my agent told me not to tell anyone what it’s about until it’s sold to a publisher. I’m telling you this because I wish I could say more, and I will say more, but I can’t say more now.

But I can tell you about an anecdote that came up in my research.

The story goes that the writer Nathan Englander was once at a dinner with Philip Roth, and he asked Roth if being an author gets easier. “My skin will get thicker with each book, right?” he asked.

“It’ll get thinner and thinner until they can hold you up to the light and see through,” Roth said.

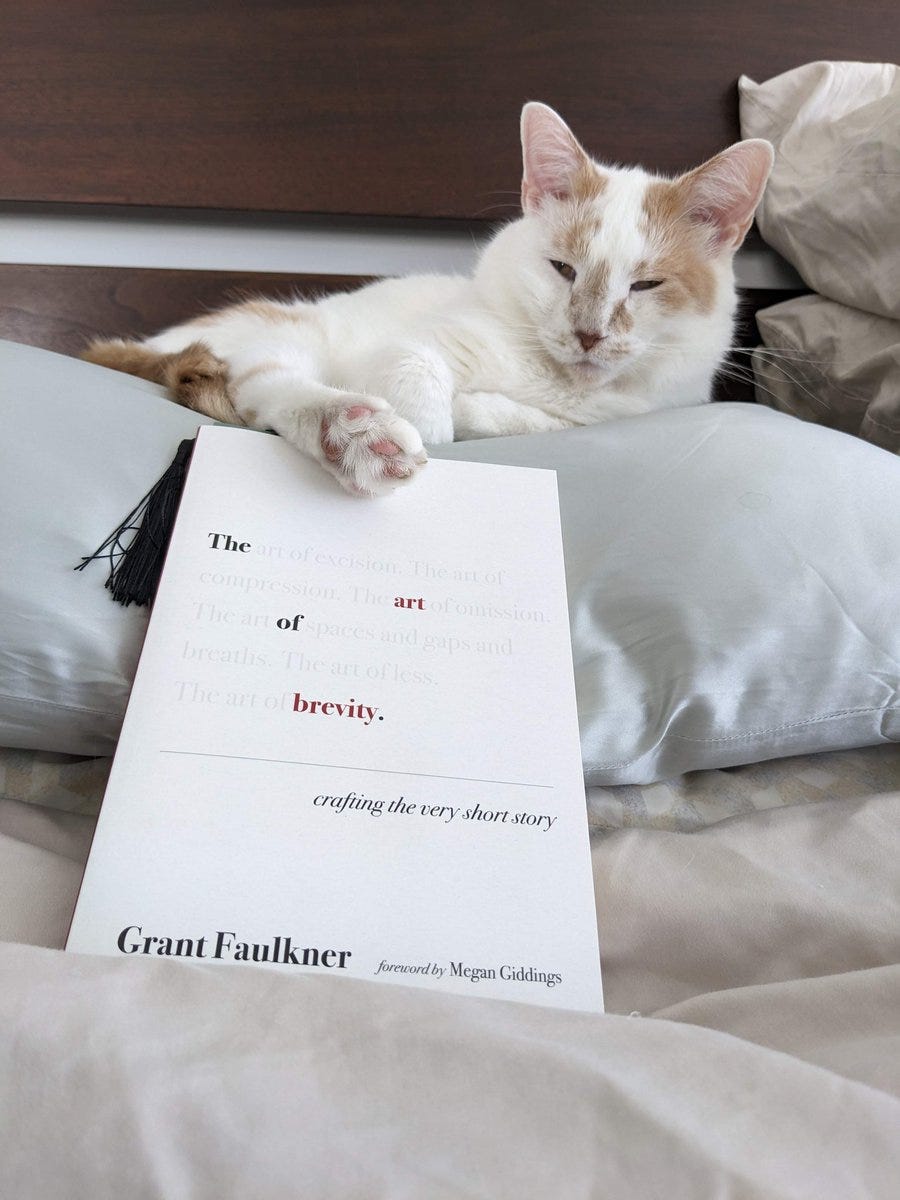

This story comes from Stephen Marche's book On Writing and Failure: Or, On the Peculiar Perseverance Required to Endure the Life of a Writer.

On one hand, it’s true: receiving a lot of rejection isn’t necessarily a good method to thicken your skin. And, in fact, it can be a good method to thin your skin, with each rejection abrading a layer of skin away.

Also, success and all of the goodies and applause and even love that comes from it doesn’t necessarily provide a cushion or a salve. Stories abound of notable authors who go off the handle at a single bad review.

So thick skin isn’t made by the quantity of rejection (although you’d think that would bring some wisdom and perspective). And thick skin isn’t made by the glories of success (although you’d also think that would bring some wisdom and perspective).

What produces thick skin? I think we can develop thick skin just like we can build muscles by lifting weights. It’s about our intent and our practice.

Roth was a notably spiteful man. At one point he wrote Notes for My Biographer, a 295-page rebuttal of his ex-wife Claire Bloom’s 1996 memoir, Leaving a Doll’s House. Bloom wrote about the pain of Roth’s cruel behavior when he left their marriage. He combed through her memoir, countering it point by point. He only dropped the book when his friends convinced him he’d look like a bully if he published the book.

But that didn’t stop his need to settle scores. He searched for a biographer who would not only refute Bloom for him—but take on every “wrong” perception and “injustice” of his life (such as not receiving the Nobel Prize for Literature, to give you an idea of the size of his ego).

Biography as revenge. Author as a weak egotist.

You’d think a lifetime of writing and thinking would nurture a wider perspective, a more generous wisdom, or a finer psychological self-awareness, but the need for retribution can be a malevolent beast that grows in size if fed hatred.

We all have thin skin. Our life, at its most basic, is a search for love and belonging, so rejection of any kind can puncture our sense of self-worth—or more than puncture. It’s a threat, and it can feel like an attack from a wild animal. Our fight-or-flight survival response kicks in. Some of us run, but some of us fight.

I was recently part of a fight scene. When given feedback—feedback given with constructive intent, with care and generosity—the person receiving the feedback reacted with hostility and resistance.

A bad day, perhaps. A bad moment. Or maybe it was part of a larger pattern, an unhealed wound that was perpetually tender.

To navigate life is not only to navigate the thorns of your own personal rejection but to navigate the thorns of others’ rejection.

It turns out we’re all wounded. Some of us search for ways to thicken our skin. Some of us, like Roth, are mired in letting every slight needle us.

Who we are as people and writers is determined by how we respond to rejection. Hopefully, we find a way to grace when rejected, but too often hostility and defensiveness set a pattern for all. A pattern that can quickly become insurmountable.

I’m not sure if anyone has ever truly settled a score or won an argument with a “revenge biography” or a revenge anything, but we’ve all felt that urge, right?

May we all use our words, as a friend of mine says. And use them with kindness.

More to come on this subject and my new book.

Because a quote

“The greatest terror a child can have is that he is not loved, and rejection is the hell he fears. I think everyone in the world to a large or small extent has felt rejection. And with rejection comes anger, and with anger some kind of crime in revenge for the rejection, and with the crime guilt—and there is the story of mankind. I think that if rejection could be amputated, the human would not be what he is.”

―John Steinbeck, East of Eden

Because another quote

“You can be the ripest, juiciest peach in the world, and there's still going to be somebody who hates peaches.”

—Dita Von Teese

What a great anecdote about what Roth said to Nathan Englander. Worth reading for that moment alone. Thanks!

I really enjoyed this. It's something I've wondered but never really thought about.