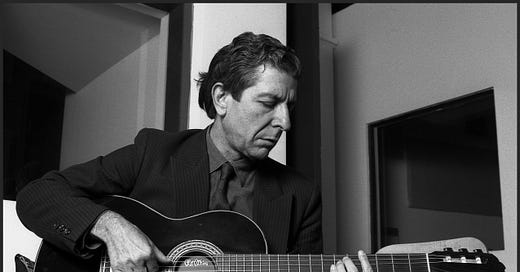

I recently had the treat of seeing HALLELUJAH: Leonard Cohen, A Journey, A Song. It was a treat not just because it was about one of my artistic heroes, but because it was a movie about the creation and the odd life of one of his songs, “Hallelujah.”

As I watched the movie, I kept thinking of how Cohen created with duende. I say the word duende because Cohen’s artistic hero, Frederico Garcia Lorca, was obsessed with duende because he believed duende is the ineffable something beyond voice and style that defines the most resonant art.

In his famous essay on duende, Lorca offered all sorts of meanings for the “mysterious force” of duende:

He recounts what an old guitar master told him:

‘The duende is not in the throat: the duende surges up, inside, from the soles of the feet.” Meaning, it’s not a question of skill, but of a style that’s truly alive: meaning, it’s in the veins: meaning, it’s of the most ancient culture of immediate creation.

Duende is the very spirit of the earth. It goes beyond any inspiration from the muse. It has “to be roused from the furthest habitations of the blood,” says Lorca.

Duende is what I hear when I listen to “Hallelujah.” I hear something beyond what I can understand, and the song was beyond what Cohen could understand. It took him five years to write it. He wrote 150 draft verses. In a writing session in New York's Royalton Hotel, Cohen is famously said to have been reduced to sitting on the floor in his underwear, filling notebooks, banging his head on the floor.

Lorca also seems to also be banging his head on the floor in order to capture duende. Here are some outtakes, with highlights of my favorite descriptions.

“Seeking the duende, there is neither map nor discipline. We only know it burns the blood like powdered glass, that it exhausts, rejects all the sweet geometry we understand, that it shatters styles and makes Goya, master of the greys, silvers and pinks of the finest English art, paint with his knees and fists in terrible bitumen blacks, or strips Mossèn Cinto Verdaguer stark naked in the cold of the Pyrenees, or sends Jorge Manrique to wait for death in the wastes of Ocaña, or clothes Rimbaud’s delicate body in a saltimbanque’s costume, or gives the Comte de Lautréamont the eyes of a dead fish, at dawn, on the boulevard.”

Duende lives on an edge, between life and death, between madness and clarity.

“La Niña de Los Peines got up like a madwoman, trembling like a medieval mourner, and drank, in one gulp, a huge glass of fiery spirits, and began to sing with a scorched throat, without voice, breath, colour, but...with duende. She managed to tear down the scaffolding of the song, but allow through a furious, burning duende, friend to those winds heavy with sand, that make listeners tear at their clothes with the same rhythm as the Negroes of the Antilles in their rite, huddled before the statue of Santa Bárbara.”

Duende is not form, but “the marrow of form,” Lorca says. Lorca notes that in Arab music, the arrival of duende is greeted with cries of “Allah! Allah!”—which is close to the “Olé!” of the bullfight—which is close to the “Hallelujah” of the Bible. Duende is an encounter with the divine.

How does one create with duende? That’s the mystery. Lorca says “the duende wounds, and in trying to heal that wound that never heals, lies the strangeness, the inventiveness of a man’s work.”

There is beauty in the wound. Cohen knew that. His poetry mentor, Irving Layton, would always ask him what he’d done wrong each day, as if making sure he wasn’t writing right, living right, because it’s not in rightness that we find the divine, it’s in wrongness, in the aberrant. The wound.

Because the act of creation is fundamentally a transgression, a disruption.

And transgression is its own kind of baptism.

“The magic power of a poem consists in it always being filled with duende, in its baptising all who gaze at it with dark water, since with duende it is easier to love, to understand, and be certain of being loved, and being understood, and this struggle for expression and the communication of that expression in poetry sometimes acquires a fatal character.”

Because no one said hallelujah to Cohen’s “Hallelujah”

Perhaps one definition of the divine is that it is rejected. I’m not speaking of the divine in a holy sense, but the holy sense probably also applies.

“Hallelujah” was originally released on Cohen’s album Various Positions in1984, which Columbia executives hated and refused to release in the U.S.

The song only found greater popular acclaim through a version recorded by John Cale in 1991, which inspired a recording of Cale's version by Jeff Buckley in 1994 that made the song truly popular (in fact, most people think Buckley wrote it). Now it’s reputed to be one of the most covered songs in history.

So the next time you fret over rejection, remember “Hallelujah.” The best of art is often initially disdained.

Because what does it mean, hallelujah?

Cohen believed that “many different hallelujahs exist.” I love that idea. And, in fact, musicians have sung the song in so many tones, ranging from the melancholic to the joyous.

This article in Rolling Stone provides an interesting take on hallelujah’s different meanings, which is a beginning tutorial in Cohen’s own obsession with capturing the duende of the word.

The word hallelujah has slightly different implications in the Old and New Testaments. In the Hebrew Bible, it is a compound word, from hallelu, meaning “to praise joyously,” and yah, a shortened form of the unspoken name of God. So this “hallelujah” is an active imperative, an instruction to the listener or congregation to sing tribute to the Lord.

In the Christian tradition, “hallelujah” is a word of praise rather than a direction to offer praise—which became the more common colloquial use of the word as an expression of joy or relief, a synonym for “Praise the Lord,” rather than a prompting to action. The most dramatic use of “hallelujah” in the New Testament is as the keynote of the song sung by the great multitude in heaven in Revelation, celebrating God’s triumph over the Whore of Babylon.

Cohen’s song begins with an image of the Bible’s musically identified King David, recounting the heroic harpist’s “secret chord,” with its special spiritual power (“And it came to pass, when the evil spirit from God was upon Saul, that David took a harp, and played with his hand: so Saul was refreshed, and was well, and the evil spirit departed from him” – 1 Samuel 16:23). It was his musicianship that first earned David a spot in the royal court, the first step toward his rise to power and uniting the Jewish people.

Because no one intones words like Leonard Cohen

Because hallelujah, my book is now a year old!

Because more about me

I am the executive director of National Novel Writing Month, the co-founder of 100 Word Story, and an Executive Producer of the upcoming TV show “America’s Next Great Author.” I am the author of a bunch of books and the co-host of the podcast Write-minded.

My essays on creative writing have appeared in The New York Times, Poets & Writers, Lit Hub, Writer’s Digest, and The Writer.

For more, go to grantfaulkner.com, or follow me on Twitter or Instagram.

This is my favorite piece you have written. You illuminate perhaps THE iconic song of our time, and expand on it and fill it and elevate it, focusing on one of the richest words in our language, HALLELUJAH, a word that transcends religion, and even God, yet is as spiritual and soulfull a word as there is. Wow!

It's interesting, there's another song that I think ranks up there with Cohen's: Handel's Messiah, of the same name. How odd that both songs capture the same duende, the same soul-lifting, ineffeble quality, that lifts you out of yourself, into the ethersphere, whether you are religious or not. How does that happen? What is it about the miraculous word?

I actually think part of it is something you hit on weeks ago: delight. Hallelujah takes your eyes off yourself and is the most human expression of delighting in something else, something that delights you, something that elevates you.

Happy birthday to All the Comfort Sin Can Provide! Like all your books, I find pleasure in rereading it. It yields new riches each time. And thanks for introducing me to the concept of duende.