For the love of words

There are these things writers use to write stories called words.

Some writers know lots of words. Other writers (like me) don’t really know too many.

But what matters most is not how many words you know, but how you use the ones you do. How you experience them and live them and touch them and breathe them and listen to them and wake up to them. And more.

One of my first lessons as a writer, way back when I was twenty and thought I knew so much about the world but knew so little (the ideal state to begin any big endeavor), came from F. Scott Fitzgerald. I read a quote by him warning that a writer shouldn’t have a large vocabulary because once you know a word, you have to use it.

What an audacious thought—that a writer shouldn’t know a lot of words. But it struck me as true because words can be like a writer’s muscles—as prominent as a body builder’s bursting biceps—and if you’ve got muscles, you’ll flex them. But big muscles aren’t necessarily strong muscles, and the most important muscles to many athletes aren’t the ones that flex in a showy way.

As I grew as a writer, I saw how some writers write within a grand cathedral of words, as if in a type of operatic worship, but others write only with the words that might be carried with them in a single suitcase, as if they’re precious keepsakes. I’ve never felt secure with my limited vocabulary, but by working only with the words that I could carry with me in a single suitcase, I think I paid more attention to the other elements of writing, such as omission, pace, rhythm, timbre, mood, and tone. I didn’t have the words to make a grand flourish of frosting for my cake, so I focused on the nuances of the cake itself.

That said, I haven’t lived in disregard of building my vocabulary. As the bryologist and Native American storyteller Robin Wall Kimmerer observed in her poetic meditation on moss, “finding the words is another step in learning to see,” so I’ve slowly accumulated words over time, and I’ve learned how words shape my thoughts, my consciousness.

Words are our guides to explore the world. They don’t just live in dictionaries, but “variously and strangely” in our minds according to Virginia Woolf. James Salter said he was a frotteur with words—”someone who likes to rub words in his hand, to turn them around and feel them, to wonder if that really is the best word possible.”

There is an erotics of language. Writers like to think of words with all of the shadings and echoes and tastes they hold. We like to hold them and caress them and fondle them. We like to intone them, to hear their music, to put them in play with other words, to discover the ways they can dance.

Perhaps that’s why words have meant so many different things to writers, why they can be morsels of delight and objects of torture at the same time. They can clarify just as they obfuscate. They can nourish just as they lacerate. They are the building blocks of reality, yet they’re nothing but images of matter and thought. They illuminate, but they also create masks and shadows.

The poet Matthew Zapruder said, “Language has emerged from our collective memory. Over thousands of years, through collective usage and trial and error, we have defined what words do and do not mean. Every time we use a word, we are, unbeknownst to us, reflecting and ratifying and perhaps slightly altering the result of all the decisions about what a word means. Our ‘tree’ is a collective version of everyone’s trees, and my tree is my version of the collective tree.”

To use words well is to be able to exist with them in both ways at once—to be able to feel all of a word’s tendrils, to be able to hold it in its original soil, and then at the same time to look at it through your personal history, as if you’re spritzing it with perfume, scenting it with the residue of your experience.

When I used to read about Flaubert’s emphasis on finding the mot juste, it always intimidated me. It felt like it was something I was insufficient in. I imagined him pursuing the correct word in a feverish state of obsessive torture. I imagined someone with a stringent, demanding mind that yielded to no compromise.

But the mot juste doesn’t have to be so anguished. It’s mainly about attention, effort, and recognition. It entails thinking of words with this dual life: as part of a history of the world in all of its branchings and as part of a deep and ever-swirling part of you, a word floating on the stream of your being, always a thing of itself and a thing being taken elsewhere.

Each time we use a word, we’re connecting with it through a fantastic infinite branching tree. Or fungi might be the better analogy—the way fungal hyphae turn into a mycelial network by branching, then fusing with other hyphae, then branching again, and so on. Life becomes not just a thing but a process, as it is with words. Words are beyond us, part of something larger than what we can truly fathom, yet they’re also deeply personal.

So, to go back to the original advice from F. Scott Fitzgerald, a writer doesn’t have to necessarily know a lot of words; a writer just needs to know how to use words. A writer has to explore a word’s nuances and layers and textures and timbres. A writer has to mix and match and play with words, looking for new pairings and possibilities.

“In each word, all words,” as the French philosopher Maurice Blanchot wrote.

Because writers like to talk about words

“There are approximately 1,010,300 words in the English language, but I could never string enough words together to properly explain how much I want to hit you with a chair.”

—Alexander Hamilton

“Words should be an intense pleasure, just as leather should be to a shoemaker. If there isn't that pleasure for a writer, maybe he ought to be a philosopher.”

—Evelyn Waugh

“The powerful intellect leashed by an impoverished vocabulary is a myth. Without a vocabulary, a language, the intellect cannot develop.”

―T. Geronimo Johnson

“Give the people a new word and they think they have a new fact.”

—Willa Cather

“Words are not as satisfactory as we should like them to be, but, like our neighbors, we have got to live with them and must make the best and not the worst.”

—Samuel Butler

“Loving your language means a command of its vocabulary beyond the level of the everyday.”

—John H. McWhorter

“Uttering a word is like striking a note on the keyboard of the imagination.”

—Ludwig Wittgenstein

“Good art provides people with a vocabulary about things they can’t articulate.”

―Mos Def

“‘Meow’ means ‘woof’ in cat.”

―George Carlin

“We live at the level of our language.”

―Ellen Gilchrist

“Language can never ‘pin down’ slavery, genocide, war. Nor should it yearn for the arrogance to be able to do so. Its force, its felicity is in its reach toward the ineffable. Be it grand or slender, burrowing, blasting, or refusing to sanctify; whether it laughs out loud or is a cry without an alphabet, the choice word, the chosen silence, unmolested language surges toward knowledge, not its destruction.”

—Toni Morrison, Nobel Prize Lecture

Speaking of Words: Remembering the Great Poet Dean Young

The poet Dean Young died last week, just a bit more than a decade after he had a heart transplant. He was a favorite poet of mine, a friend, who I read to think differently (that was a guarantee of Dean’s poetry: his poems recast the world). Beyond his poetry, he wrote one of my favorite writing books, The Art of Recklessness.

Several days after he died, I remembered a blog post I wrote about his poetry, and about his book Skid, in 2008.

Dean Young is an easy poet for me to like. His congenital, sometimes twisted, joie de vivre leaps off the page. He’s a prankster, a Dadaist, a writer whose words and images juke, jab, dash, pirouette, and jump—just when you think you know where one of his poems is going, it changes course like a dare.

He’s one of the few writers who can surprise with each phrase, if not each word, tossing coarseness into a highbrow thought, switching from the sanguine to the lugubrious in a snap of the fingers. He rarely settles for a single note in his poems, in fact, but allows a playful, discordant, dreamy contention of words to define his universe.

Because there’s always a new word: chortle

Language is never static. It is always evolving, and new words appear in strange and magical ways.

Lewis Carroll invented “chortle,” a favorite word of mind, in Through the Looking Glass. It means to laugh in a gleeful way. But it means so much more than that, right?

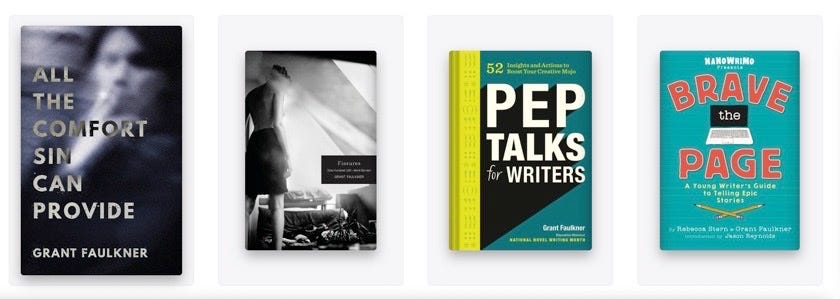

Because I’d love you to read one of my books

I write for many reasons, but mainly just for the joy of being read and having conversations with readers. This newsletter is free, and I want it to always be free, so the best way to support my work is to buy my books or hire me to speak.