Found Objects, Found Stories

Making the detritus of the everyday into gems and jewels

There’s always the question: Do we find our stories or do our stories find us?

It’s a little of both for me. I’ve always thought my true calling was to be a junk collector, perhaps even more than being a writer. I love patinas of rust. I love ragged, torn clothing. I love finding abandoned items on the street. I save old plastic jewelry, torn-apart wrapping paper, and random shiny objects in a big box called my “collage box.”

Similarly, I keep a doc I call “stray phrases,” which is its own type of junk shop, a collection of odd sentences—stiff, voluptuous, rapturous, restrained, or just plain kooky, all of them special for a reason I likely can’t articulate. I just like them.

W. H. Auden described a poem as being written by connecting the best lines from his notebook, which mirrors the way I tend to write, especially when it comes to flash fiction.

Somewhere in the mix of having kids (and not having much time) and living in a state of perpetual transition—on buses and subways, standing around on playgrounds—I started carrying a notebook in my back pocket, which was a type of net to capture stray thoughts, overheard conversations, lines from a book I was reading. My random jottings formed themselves into my creative process.

The beauty of my jottings is that they don’t demand anything. In fact, they’re likely not to turn into anything. But I type them up and either place them in my “stray phrases” doc or in any number of other docs where I have works in various stages of dress and undress.

Flash fiction allows the rags and detritus of the everyday to become gems and jewels. To be a junk collector is by definition a practice of looking at the world differently: finding purpose in other people’s castoffs, beauty in other people’s trash. Flash fiction is similarly experimental because brevity changes the contours of a conventional story. A flash story can be a list, a letter, a text exchange, a Twitter argument.

Flash fiction allows one to walk through the world as a junk collector might.

“Part of the fun of writing them is the sense of slipping between the seams,” said Stuart Dybek. “Within the constraint of their small boundaries the writer discovers great freedom. In fact, the very limitations of scale also demand unconventional strategies.”

Because of its size, flash fiction invites using forms of writing that we use every day, but in new, inventive ways. I’ve written stories in the form of customer reviews of Dansko clogs or a guest’s entry in a bed and breakfast log.

Leesa Cross-Smith’s “Girlheart Cake with Glitter Frosting” is a recipe that comprises a feast of ingredients that make up girlhood, including “too much black eyeliner,” “champagne from a can,” and “‘Music to Watch Boys To’ by Lana Del Rey.” Michael Czyzniejewski uses the form of an outline in his story “The Braxton-Carter-Van- Damme-Myers-Braxton-Carter Divorce: An Outline.” Kathy Fish uses the form of a dictionary entry in her commentary on human nature, “Collective Nouns for Humans in the Wild.”

Kim Magowan wrote a brilliant one-hundred-word story, “Madlib,” in the form of a Mad Lib. Sam Martone uses the 404 error page on the Internet in his story “404—Page Not Found” to tell a long-winding story that builds on the cold tech speak of remediating an error with personal digressions of the page’s anonymous author. Lucy Zhang uses the how-to form in her sultry hybrid piece, “How to make me orgasm,” which also includes the language of engineering manuals, business speak, and cuisine to evoke her narrator’s sexual needs.

The found objects don’t have to be narrative texts but can be more visually oriented. Alex McElroy uses a flow chart to tell the story of a son, a family, while showing the branching paths of living and dying in “The Death of Your Son: A Flow Chart.” And Kristen Ploetz tells the story of a character’s life events through colors in “LifeColor Indoor Latex Paints®—Whites and Reds.” She inventively divides life into the colors of whites and reds, starting with the first light of birth (Hospital Light—AR101).

Text is two things at once, as Annie Dillard said about turning a found text into a poem. “The original meaning remains intact, but now it swings between two poles.”

Indeed, a found text always has a complicating or dramatically expansive layer. For example, Lawrence Sutin’s A Postcard Memoir is constructed with duotone reproductions of postcards. Each postcard image, as if found in a box in the attic, is paired with a story, creating an odd juxtaposition that recontextualizes his past. The episodes take on a different tone of narrative because they’re missives from the past.

Flash can animate ordinary places of discourse, alert us to the stories within otherwise pedestrian prose. It allows one to walk through the world as a junk collector might, looking at the different narrative objects that surround us and wondering if they might be vessels for a story.

Excerpted from The Art of Brevity.

Because The Art of Brevity

One way to support this free newsletter is to buy my new book, The Art of Brevity (the words of my gratitude might be brief, but they run deep).

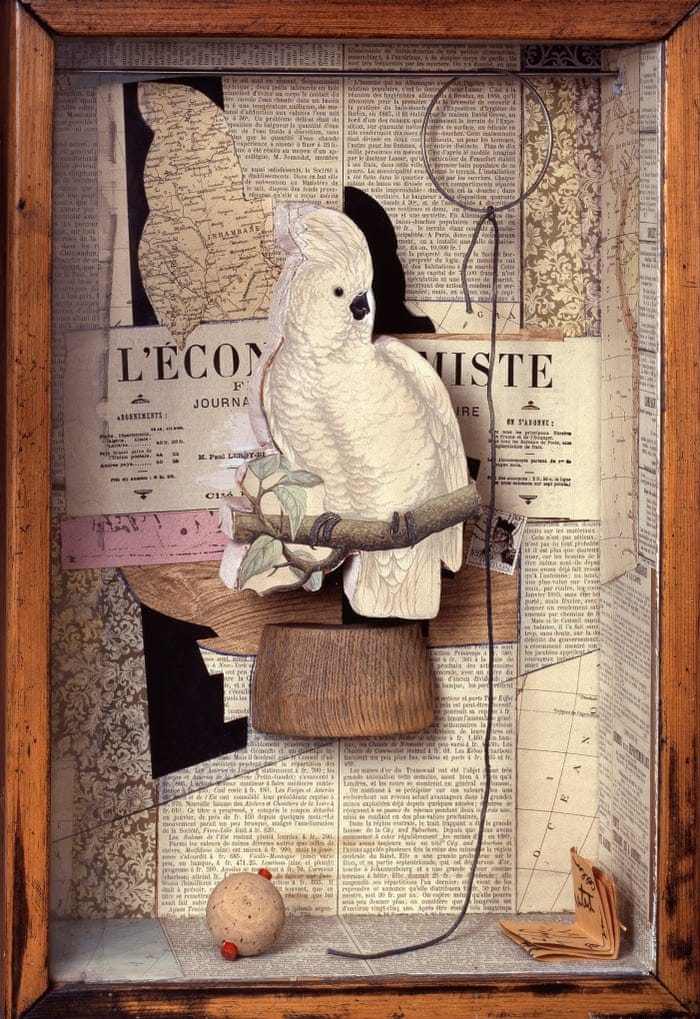

Because Joseph Cornell

The image above is one of Joseph Cornell’s “assemblages.” Cornell was a storyteller who created narratives through bric-a-brac that he put together in boxes. He’d walk aimlessly through the streets of New York City, finding discarded treasures for his art: cork balls, metal springs, old photographs, dime-store trinkets, and so on.

His art was defined by the hunt for the unwanted, for insignificant detritus, which he then archived and reassembled to make new worlds: poetic “assemblages” or “shadow boxes,” known as “memory boxes” or “poetic theaters.”

He filled cardboard storage boxes with his found treasures and organized them as if they were in a museum’s back room, each of them labeled. He attached the highest value to objects of little or no intrinsic worth. A box labeled “tinfoil” or “plastic shells” resided alongside another marked “Caravaggio, etc.,” hinting at Cornell’s belief that great painters were no more important than the discarded objects of everyday life.

Because a writing prompt: junk collecting through words

Collecting junk naturally leads to playfulness because of the way randomness and the accidental is part of the process. Go on a random search for text you might create a story with, or text that might stand alone as a story. Look at your junk mail, the letter you receive with a new credit card offer. Look through the emails in your spam folder. Go to the library and read through old newspapers or diaries.

See how you can give the “junk” you find a new and different life through the simple frame of a story, a new context. The junkyard of stories is a playground of possibilities.

Because you can attend my book events via the internet

Because more about me

I am the executive director of National Novel Writing Month, the co-founder of 100 Word Story, and an Executive Producer of the upcoming TV show America’s Next Great Author. I am the author of a bunch of books and the co-host of the podcast Write-minded.

My essays on creative writing have appeared in The New York Times, Poets & Writers, Lit Hub, Writer’s Digest, and The Writer.

For more, go to grantfaulkner.com, or follow me on Twitter or Instagram.

‘The junkyard of stories is a playground of possibilities.’ Going to soak this up and spit something out on paper! Thank You Grant!

Your book (which, physically is beautiful) and your interview on your show, write-minded, motivated me to launch into the 100-word story world. Wow! What fun that is. You were a '10' in the interview...just perfect. Understated, insightful, and interesting...all the things a podcast guest should be (even though it was your own show). Brooke is the best!

Your book is just great, too. I'm loving it and will leave a review today. Congratulations.