New ways of running (as a creative metaphor)

I like intensity. I like pushing boundaries. I like exerting myself to the limits of exhaustion. And then some.

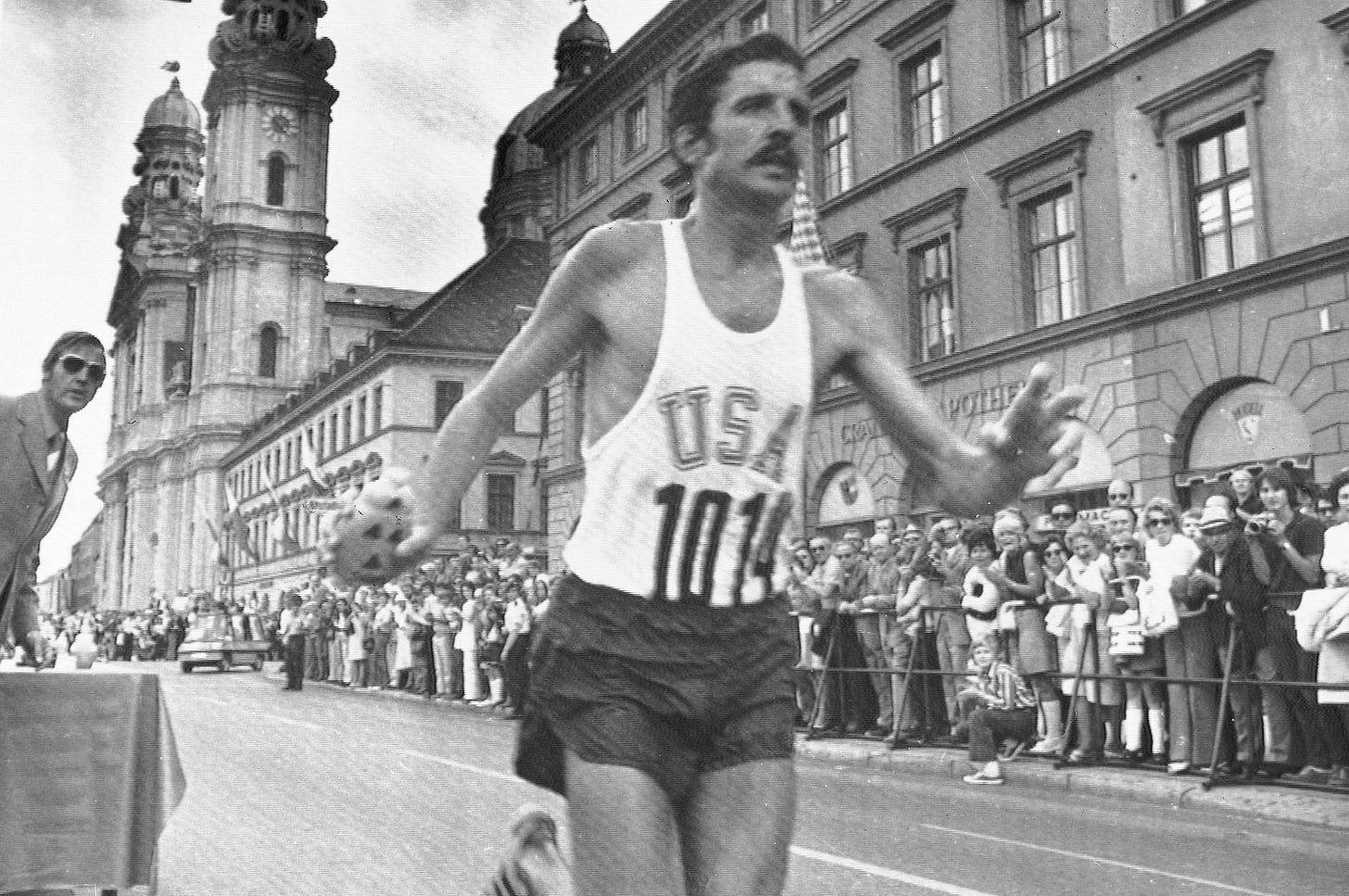

That’s why I was drawn to long-distance running as a kid. I still remember watching Frank Shorter win the marathon in the Olympics in 1972. His lanky body. The gaunt endurance in his face. His steady stride. There was a majesty as he entered the coliseum, the sense of a soldier coming home after a long and punishing voyage. I didn’t know someone could be so exhausted, and I wondered if he’d collapse in that last lap.

I knew then that I was a runner. I knew it like I knew I was a writer. It just happens that long-distance running is a good metaphor for being a writer (and vice versa). It’s hard to explain the strange pleasure of endurance, of running (or writing) through pain, but it’s next to holy for me. I get lost in the rhythm of my stride just as I get lost in the footfalls of the words in my sentences.

I ran cross-country in high school, and I was good, one of the best runners in the state for a while, and that was a powerful and marvelous feeling. But then my friends and I discovered the joys of drinking, and as budding alcoholics, we started pushing a different kind of limit.

I’d go out the night before a race and drink into the wee hours. A stupid teen thing. I knew only the moment, especially with a bottle in my hand. But I never missed a race. I’d usually throw up in the first half-mile, but then I’d feel the juice kick in, and I picked up momentum as I passed runner after runner—a great pleasure. I took particular joy in sprinting ahead of runners on a steep hill.

I didn’t usually win, but I had my fun. I liked the game of coming from behind—it was more fun than protecting a lead (the same goes for writing). I felt like I’d eventually pass everyone and win, and every once in a while, I did.

Flash forward 40 years. A lot of that pushing boundaries and exerting myself to the limits of exhaustion in all sorts of things got me into a pickle of some health problems, so now I’m not supposed to exert myself beyond very moderate limits. I used to lift weights at the gym, in addition to distance running, but now I’m not supposed to pick up heavy weights or my heart might explode, literally, because of an expanded aortic root. Instead of pushing boundaries, I enforce limits.

So I’ve become a walker. The Frank Shorter of late middle-aged walking, you might say. I like the rhythm of a good amble, how my thoughts start to loosen and flow with my strides. But the thing is I’ve never quite gotten comfortable with how walking is, well, walking. How I’m not building the strength I used to build in my workouts at the gym or pushing cardio limits to go further faster (I yearn for that feeling).

Then I read a piece in The New York Times about turning your walk into a workout. One of the suggestions to level up your walks is to get your arms involved by wearing wrist weights, so I bought a pair of two-pound wrist weights.

Wrist weights?

I’d never imagined myself as the type of person to wear wrist weights—not me, not one who pushed the extremes of exertion—but I snapped the two-pound weights around each wrist and proceeded on my inaugural walk.

What was immediately evident was that they did nothing for me if I just walked normally, so I started swinging and lifting my arms in a movement I’d learned from Qi Gong. Then I lifted them over my head as I walked, pushing the repetitions to the point of muscle tension. Then I shadow-boxed with them as I walked.

What was wonderful about the weights is that they forced me to think and move differently. They added a layer of experimentation, playfulness, and creativity to my walk.

At one point, I suddenly realized I might look silly to an observer with all my weird arm swinging and lifts. But I didn’t care. Because it was fun. And I felt myself getting stronger. Just a tiny bit. I wouldn’t develop a weight lifter’s big muscles, but I no longer have a need for big muscles. That’s one nice thing about aging, along with being comfortable looking silly.

So how does this all add up to a creative tip, a writing meditation? How about this: What can you do to move differently, to change something you do regularly—the equivalent of swinging your arms to change your stride (and maybe look silly while doing it)? What can you do to level up with “small weights”—write for an extra 10 minutes? Read for an extra 10 minutes? Write a tiny story instead of a big story?

Just be sure not to drink a lot the night before a race. I no longer drink, and it’s perhaps the best thing I’ve ever done for my writing. I also don’t pass any runners, but that’s nice, too: I often walk just for the companionship of another (so there’s another metaphor to apply to creativity).

“We’re all just walking each other home,” as Ram Dass said.

Because writing is composting the mess

“Writers always live their lives facing backward, considering things we said or could have said, or things we wish we could take back. The work we do is precisely about trying to clean up the mess we made, the kind of emotional footprints we leave behind, or the mess we inherit. Maybe we didn’t even make that mess, but it came to us because we were witnesses. That’s the work we have to do as writers, to help compost all this junk that’s out there. It’s like this emotional composting until we’re able to transform it into something beautiful. That’s the work we do, and it’s not any less valuable or remarkable than anybody else’s work.”

—Sandra Cisneros

Because a koan about creativity

Life is largely a matter of building up and tearing down. Sometimes in the building up, we tear down (if we’re not wise). Sometimes in the tearing down, we build up (if we’re wise). But sometimes you’ve just got to tear it down. And sometimes you’ve just got to build it up.

Because writing is like pitching

I’m always looking for new metaphors to describe the creative process. I was so entranced by this piece in the New York Times, My Unlikely Writing Teacher: Pedro Martinez, by Will Harrison.

Harrison compares artful writing to artful pitching in a way that perfectly captures the experience for me.

“This is what writing feels like lately,” I wrote in my journal. “It’s all about pitch sequencing, about sentence variation. You have to move the reader through the paragraph. Fastball, curveball, changeup. Normal sentence, long sentence, short sentence. Straight declarative sentence, periodic sentence, sentence fragment. Keep them on their toes, keep throwing the ball past them.”

I’m always thinking about the role that rhythm and movement play in my own prose and in the prose of my favorite writers; I love the way that language can leap from my mind and then to my fingers, much like a curveball arcing out of the hand of an All-Star pitcher. I studied Martinez, first as a baseball player and then, eventually, as an artist — I close-read him as you would a Modernist author. I came to learn that he is an excellent writing instructor, as wild as that sounds. His signature games are a master class in how to shift registers, how to strategize, how to create forms and patterns and leitmotifs. From Martinez, you can learn how to perform on the page.”

Because I have an event coming up

Join me on August 7 at 4 p.m. at Shack15 in San Francisco’s Ferry Building!