Quitting

In this world of clogged Inboxes full of stubborn emails that keep arriving even after you’ve unsubscribed—pitches, promotions, news, demands—it’s rare to actually be surprised, entertained, or nourished by a stray email.

I had that experience recently via Richard Nash’s newsletter, “The Dinner Party Letters.”

“Newsletter” might be overstating it, though. In January of 2021, Richard sent his first newsletter, which he planned to send monthly. Richard subscribed me to his list, without me knowing it, and, yes, I was a little annoyed by that, but Richard is such an interesting raconteur, wit, and divergent thinker that I didn’t unsubscribe, and I liked the first newsletter, so I decided to give it a chance.

I didn’t notice that the promised newsletters didn’t arrive, but then the second newsletter arrived, two years later. I only had a faint memory of the first newsletter, but I was immediately charmed by the irregularity of the newsletter. I loved the notion of sending newsletters so randomly that they’d seem like precious little gifts.

I was also charmed by Richard’s “failure,” and the way he grappled with it.

But while I did type “sigh” there, and while I did periodically feel embarrassed, irritated, while I did chastise myself for overpromising and underdelivering, I had moments of feeling a certain glee. For I was giving myself something I so often find myself wanting to give others, something I so often want others to give themselves—permission. Permission to not have to write a second. goddam. letter. You should write your second letter, Richard, it’s been so long! Who says, I retort. Who says I should? Who decides what is “should” vs. “who cares”?

That “certain glee” is a mental state we should all reflect on. It’s the glee of playing hookey. It’s the glee of accepting yourself. It’s the glee of seizing yourself. Or the glee of giving yourself permission, as Richard puts it.

Richard went on to meditate on the glee of quitting via the book by the professional poker player Annie Duke, Quit: The Power of Knowing When to Walk Away.

We live in a culture of determination and perseverance. We celebrate resilience, grit, and fortitude. No pain, no gain, right? Just do it. Whether you’re an Olympic athlete or a novelist, you’re celebrated for your mettle, your discipline, your drive—all necessary for success, certainly.

“Winners never quit and quitters never win,” as Vince Lombardi said, and our world swarms with such mantras.

Quitters are losers. “They are backtrackers, chickens, defeatists, deserters, dropouts, shirkers, wimps, and wusses,” writes Richard. “They give up and abandon things, waver and vacillate. We consider them aimless, capricious, craven, erratic, fickle, weak-willed, undependable, unreliable, and even untrustworthy.”

And yet sometimes it’s best to quit. As Kenny Rogers famously sang: “You’ve got to know when to hold ‘em, know when to fold ‘em.”

Annie Duke gives the example of climbers who persisted to climb Everest in dangerously inclement weather and died as a result—yet are viewed as heroes. We celebrate perseverance even when it’s unhealthy.

I’m mulling this over because I’m often asked how to know whether to continue writing a novel when you feel that it’s boring, worthless, unoriginal, etc. It’s tough because every writer I know has felt that their novel is boring, worthless, and unoriginal at some point in the process—or at several points in the process—but they persevere. I don’t know of a book that gets written without huge doses of perseverance.

And perseverance is not only an ingredient of finishing, it’s a key ingredient in the magic of imagination itself.

Duke says that any time we start a new venture, we start in a state of uncertainty. We gather information as we go, and sometimes that information tells us our endeavor isn’t right for us. That’s the moment to do the one thing in your control: quit.

There’s not necessarily a science of quitting. It’s a feeling. It’s an art. And the art takes years of practice, years of persevering on projects you should have quit and years of quitting projects and never thinking of them again. Years of attunement to know how to listen to yourself and identify the force (or the withering) of your creative drive.

The thing about perseverance is that it’s not a single thing. Perseverance is fueled by curiosity, desire, hunger—by a need that can be overwhelming. Perseverance is fueled by purpose, by the feeling that you have to do this thing or life will lose its meaning. At its best, perseverance feels holy, meaning that you’re serving a higher power, you’re working for something beyond yourself, so discipline doesn’t feel like discipline. It feels like breathing.

But if perseverance isn’t fueled by these things, if it’s just willed, if it feels forced, perhaps it’s time to quit. I wonder if the decision to quit is a little like the Marie Kondo exercise of holding an object and asking yourself if it gives you joy, and if it doesn’t, it’s best to get rid of it. The same process can apply to creative work.

“Quitting, when done right, allows you to achieve your goals more quickly,” says Duke. “This is counterintuitive, because we think of quitting as stopping our progress. But that’s not true when the thing you started isn’t worthwhile. If you quit, that frees up all of those resources to switch to something that will actually help.”

When I think of the words Richard listed for quitters—capricious, aimless, erratic, etc.—I think about how they can also ironically be vital sources of creativity. To waver, to drift, to shirk, to wander. Some of my best moments of life have occurred when I played hookey, when I fell into myself by not showing up.

So the question: What can you quit that will give you a “certain glee”—the glee of freedom? What can you quit that will fuel your creative work?

Because I’ve got a couple of things going on

Thursday, April 20, 2023, 6:30 - 8:00 p.m.

Kepler's Books, 1010 El Camino Real, Menlo Park, CA, 94025

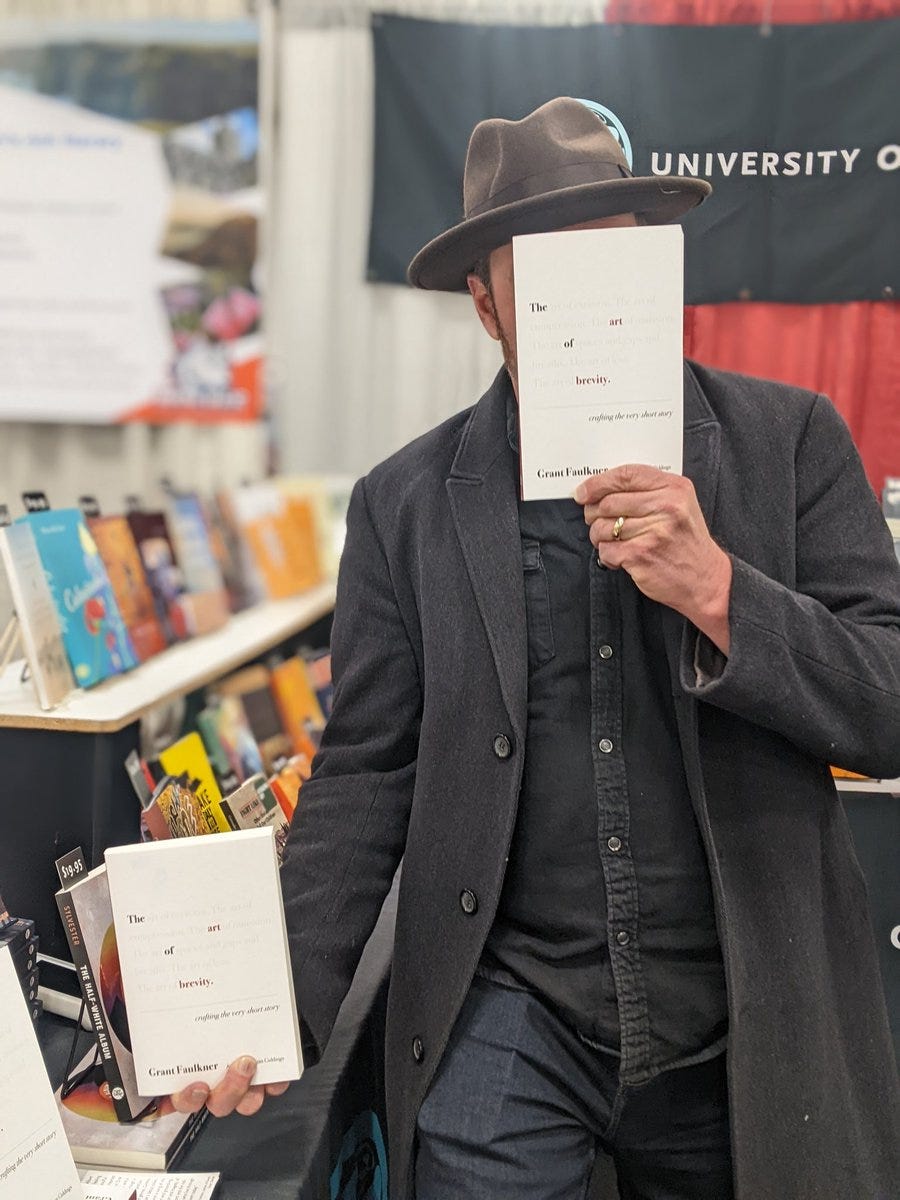

I’m teaching a two-hour online class, Five Things I’ve Learned about the Art of Brevity, Sunday, April 30, at 5:00 p.m. Pacific.

I’ll talk about such things as omission, how creativity is enhanced by constraints, how a writer of flash fiction has to be a master pruner, and much more. This will be a Zoom format, so you can ask questions. Also, prepare to write!

Because a quote

"If you just sit down in front of the screen and read what you wrote yesterday, that's enough. Writing is all about the unconscious, and the unconscious should be checking in with the story every day."

—Walter Mosley

Because an excerpt: plotting in miniature

One of the most frequent questions I’m asked about writing 100-word stories is whether a 100-word piece can have a plot (with a beginning, middle, and end and a character change) since it has so few words.

The answer is yes, but ... I like the short form for the different kinds of plot structures it allows.

Thanks to SmokeLong Quarterly for publishing this excerpt from my new book, The Art of Brevity, on plotting in flash fiction.

Because The Art of Brevity

Please consider buying my new book, The Art of Brevity. Writers tell me they like it. You might say it’s my way of being a poet in this world. My little stories are my little prayers. I like to drop them into the world.

Because more about me

I am the executive director of National Novel Writing Month, the co-founder of 100 Word Story, and an Executive Producer of the upcoming TV show America’s Next Great Author. I am the author of a bunch of books and the co-host of the podcast Write-minded.

My essays on creative writing have appeared in The New York Times, Poets & Writers, Lit Hub, Writer’s Digest, and The Writer.

For more, go to grantfaulkner.com, or follow me on Twitter or Instagram.

There is a need for moderation in everything, including perseverance. Thank you for this thoughtful reflection. Blessings

Great reflection on quitting vs persevering! This binary is one of the most important dynamics in how we manage our lives, but little discussed, since perseverance is enshrined as the ideal.