The Art of Aging: No More F*&ks to Give

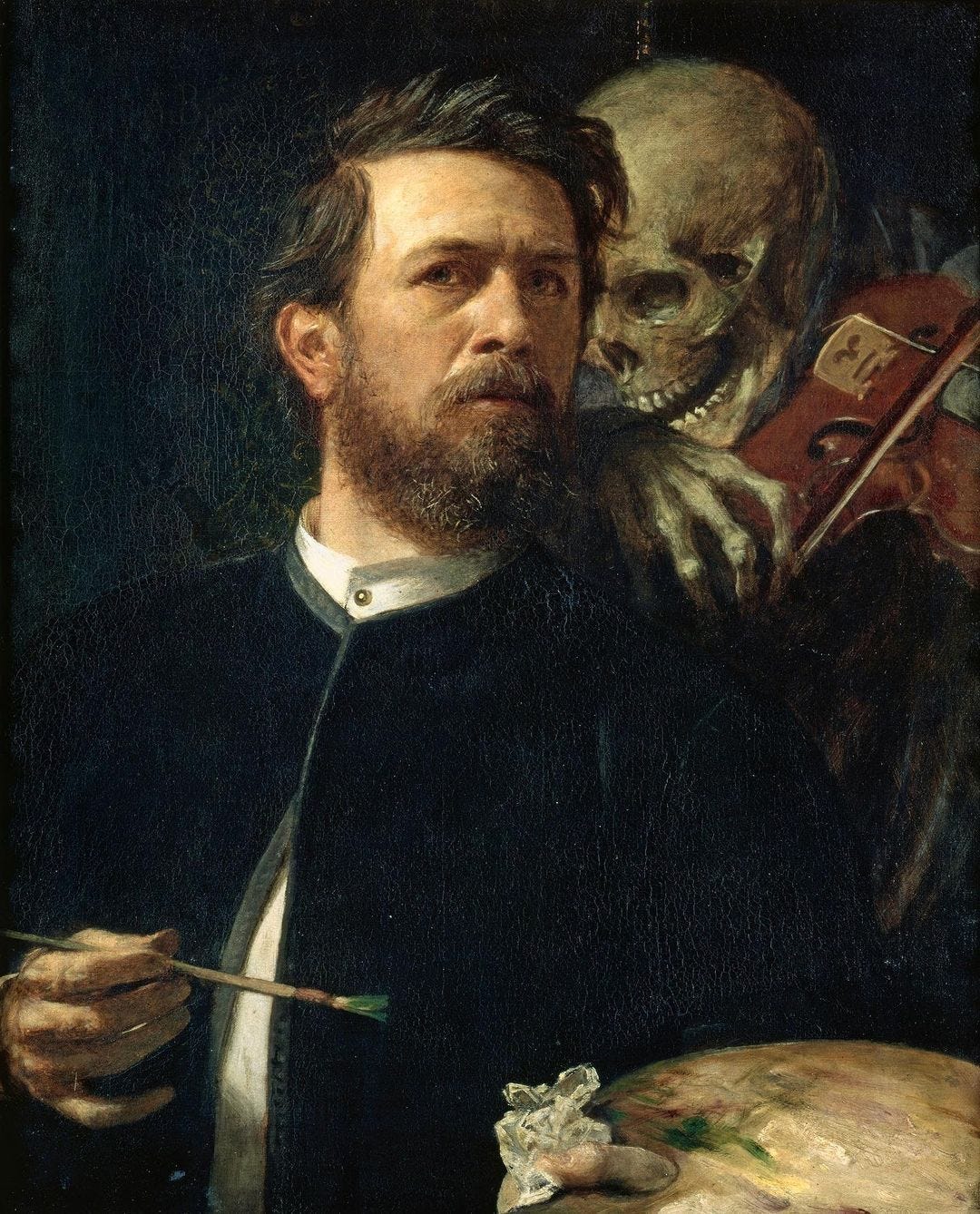

A gift of getting older: art driven by defiance, by revelation, by truth

The most common regret people have on their deathbed is that they wish they had lived a life more true to themselves.

I can’t imagine how painful that must be: To have lived this long life and not quite lived it as yourself, to not have accepted yourself, to not have expressed yourself.

One definition of life: we become expert at beating ourselves up. Many of us regularly lash ourselves with self-recriminations, and we learn early on that it’s better—or safer—to hide parts of ourselves.

So words aren’t spoken, kisses aren’t ventured, and dances aren’t danced.

Most people “lead lives of quiet desperation,” Thoreau wrote in Walden, but they also lead lives of quiet shame and self-doubt, if not self-hatred.

I’ve been thinking a lot about aging and expression since I recently aged into a new category (the “third act”) of life, and I talked about some thoughts in an interview with

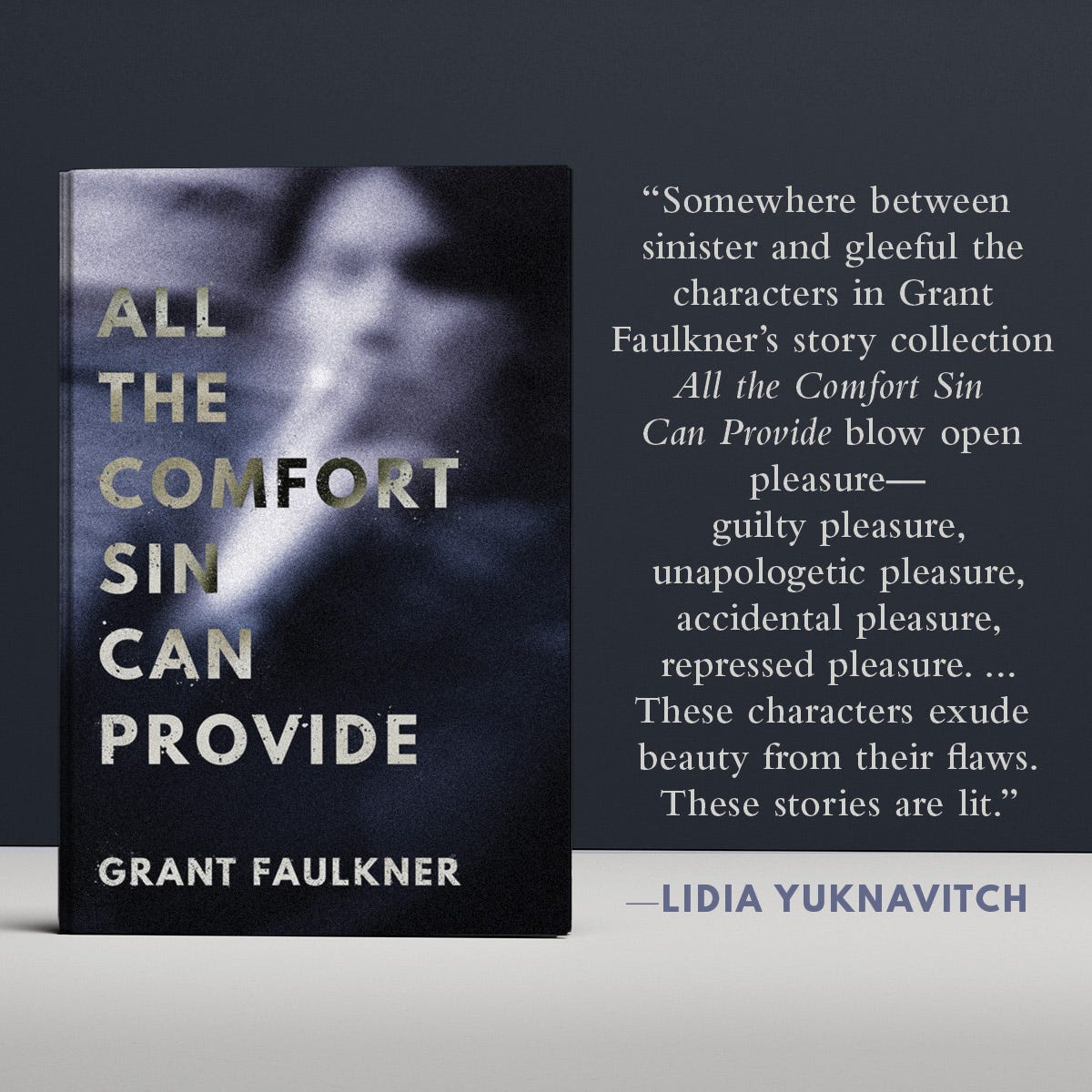

last week—This is 60: Grant Faulkner Responds to The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire.Fortunately, on the positive side, I’ve mainly read stories about how many people are more motivated to embrace their true selves as they get older—or because they’re getting older.

As mortality creeps closer, truths roil within, and they’re mutinous, without fealty to any of the past decorums.

The two are related, aging and truth telling. Our bodies physically fall apart with age, but I think our minds also weaken with the exhaustion of vigilantly guarding our true selves, and we realize our souls can only become enlivened by the wondrous glimmerings of authentic expression—and the connections that result.

And trust me, when you reveal yourself, connections will abound. That’s what I’ve found, in this newsletter, in my other writings, in life. People are hungry to hear another’s truth, which is one of the reasons that as a person, but especially as a writer, one of my personal mantras is to be more forthcoming with my sins and my shames and my self in all ways as I get older.

Because I think it’s our duty as writers to lead the cause of expressing what it means to be human. That’s the holy goal we need to be in service to, like a monk practicing devotion to the divine. We need to put the messiness of this life in better perspective for others. It’s one of the things we can do better than the young.

‘Waking up to ourselves’

When I turned 60, I felt as if I walked through a door with the words “No more fucks to give” scrawled upon it. As mortality creeps closer, truths roil within, and they’re mutinous, without fealty to any of the past decorums.

As Maya Angelou said: “At 50, I began to know who I was. It was like waking up to myself.”

And in waking up to yourself, you speak yourself, because we fundamentally seek to be understood—a desire that forms the motivation and inspiration to make art.

There is an insurgency lurking within us all, so we have to dare to rebel against the rules, the norms—because that rebellion is actually an act of love and reverence for our voice.

“To be truly alive is to feel one’s ultimate existence within one’s daily existence,” wrote the poet Christian Wiman.

We feel our “ultimate existence” more urgently as we age, and it makes demands on our daily existence. One definition of a soul is the stories we leave behind, and that is a gift of aging—to feel our ultimate existence as a call to shape our daily existence around our truths.

Reimagining the “looking-glass self”

In my Oldster Magazine interview, I was initially surprised when several people thanked me for being so open, or told me I was brave to do so. It’s a paradoxical thing for me: on the one hand, I’ve trained myself for a certain degree of revelation as a writer, so I’m practiced in it and don’t think about it too much, but I am always nervous that I’ve told too much, or told it in the wrong way.

I’m not a confessional writer by any means, and I tend not to write about my life directly in my fiction (although I am increasingly probing myself in my personal essays and the memoir I’m working on).

But creating art is an exercise in opening the self, and one of the big benefits of aging is realizing why not? Why not write about the things we’ve tended to hide? Why not unearth supposedly shameful experiences and let them breathe in the world?

Diana Athill, in her memoir Somewhere Towards the End, wrote about the liberating aspects of aging, noting how she found herself caring less about others’ judgments and more about living authentically.

A central theme is her discovery that aging brought freedom from the “looking-glass self”—that constant awareness of how others might view her. She writes about how in her younger years, she was always partly performing for an imagined audience, particularly in romantic relationships. As she aged, she found herself free of that burden.

We’re all performing, at least in part, for an imagined audience. What if we re-imagine that audience more to our liking? What if we re-imagine that audience as one that is friendly and encouraging of our stories, our selves? I wonder what stories will emerge?

I think this is what gradually happens with aging, in the best cases: The audience is re-imagined—or it just disappears.

This week’s creative challenge

My challenge to you this week is multi-pronged:

Do the Oldster interview yourself as a way to reflect on aging (and re-take it every five years to see how your answers change). Oldster’s premise is that we’re all oldsters because we’re all aging, so you don’t have to be “old” to take it.

Ponder how open and authentic you allow yourself to be, and if aging is reshaping your openness

How can you make your truth part of your creative process? How can you re-imagine your “looking-glass self”?

Read This is 60: Grant Faulkner Responds to The Oldster Magazine Questionnaire.

Spare a dime to help me publish this newsletter?

Please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Because some quotes about aging and creativity

“It takes a long time to become young.”

—Pablo Picasso

“The great thing about getting older is that you don’t lose all the other ages you’ve been.”

―Madeleine L’Engle

“Women may be the one group that grows more radical with age.”

—Gloria Steinem

“Age has given me what I was looking for my entire life—it has given me me. … I have become the woman I hardly dared imagine I would be.”

—Anne Lamott

“There are years that ask questions and years that answer.”

—Zora Neale Hurston

“The tragedy of old age is not that one is old, but that one is young.”

—Oscar Wilde

“Today I am 65 years old. I still look good. I appreciate and enjoy my age. A lot of people resist transition and therefore never allow themselves to enjoy who they are. Embrace the change, no matter what it is; once you do, you can learn about the new world you’re in and take advantage of it. You still bring to bear all your prior experience, but you are riding on another level. It’s completely liberating.”

—Nikki Giovanni

I’m available for book coaching and editing!

I love working with writers, and I have some space on my Writing Consult calendar if you’re looking for help.

I help people develop books and projects from scratch and sometimes do larger edits on finished manuscripts.

Lately, I've worked on novels, memoirs, and some short story projects. I’ve also worked on helping people figure out what kind of writer they are or want to be, and which projects can help get them there.

Contact me to find out more about my one-on-one work with writers.

“But creating art is an exercise in opening the self, and one of the big benefits of aging is realizing why not? Why not write about the things we’ve tended to hide? Why not unearth supposedly shameful experiences and let them breathe in the world?” Love this! I write about growing up with parental mental illness. At age 50, I find myself brave enough to break my silence and find my voice to tell my childhood stories.

Excellent article. Two comments:

I worked for over 30 years at Synectics, a leading consultant in creativity and innovation, as a senior partner. One of the founders, George Prince, as he aged began experimenting with creativity for oldsters. He found that the main issue was they had lost the ability to "image" and that it was a relatively easy skill to reawaken. I know he designed some workshops around that but I'm afraid they were lost when he passed.

Besides writing I have a trick to deal with aging. After sixty I started adding a year to my age. SO when I turned 65 I considered I was in my 66th year, and when asked said I was 66. But I knew it wasn't true. Then. When I turned 66, it was duh! I've been saying that for a year : )