Because happenstance—in life and art

So many things in life happen randomly.

One night in 2010, my friend Jake posted a link on Facebook to nine 100-word stories his father, Paul Strohm, had published with the literary journal Eleven Eleven. It was late, my eyes were blurry, but I clicked on the link and became intrigued by the series of tiny tales that were part of his memoir, Sportin’ Jack, which consisted of 100 one-hundred-word stories.

I liked the stories because they were little snapshots that allowed Paul to tell his life story through key pivotal moments instead of a larger memoir with a big narrative arc centered around major events.

Our lives are about small moments—or small moments that are actually big moments. It was as if Paul’s stories were photos in a Kodak carousel, flashing from one life moment to the next. In fact, he told me he modeled the form as if writing with a fixed-lens camera, with the idea that an arbitrary limit inspired compositional creativity.

I’d been working off and on for 10 years on what I now call my “doomed novel,” which had not only begun to weigh down my creativity but weigh down my life as well, so I decided to take a break from it and try my hand at writing these tiny stories.

I also just wanted to shake up my creative process. I’d been writing towards “the more” all of my life, after all. “More” is a key word in learning to write. We level up as writers, writing longer papers and using bigger words and longer sentence constructions at each academic stage because we’re taught that serious, sophisticated thoughts need more of everything to be conveyed.

Brevity allows us to get close to the unsayable, to know something that is beyond words or the wordless moments words bring us to.

Most of my writing life had been a training ground of “more,” in fact, so I rarely conceived of writing less. Even when I got my MFA, I frequently heard the comment, “I want to know more about _____” in many of the creative-writing workshops I took. More characterization, more backstory, more details—more of everything.

Rarely did anyone advise places to cut or condense or write less. None of us stopped to ask if this “more” added to the story or if it was just a passing curiosity of the reader’s, a need to have the story spelled out instead of imagined. I wrote longer and longer short stories, and then I wrote longer and longer novels, trying to fill in gaps, not open them.

So I began writing 100-word stories—I began writing less—and I learned that the short form is beguiling. Since it’s so short, it would seem to be easier, but in my initial forays I couldn’t come anywhere close to the one-hundred-word mark. At best, I could chisel a story down to 150 words, and I was so frustrated by the gobs of material I’d left out that I didn’t see a way to go further.

I told Paul that I’d written several stories as short as 150 words, and I told him I was pleased with that level of brevity, but he chided me to keep going farther, to trust that my story would actually get better as I cut it down. I didn’t quite trust that, but I kept going. The one-hundred-word form had become a riddle to solve.

I began to think of how the chants of “more, more, more” I’d heard in my writing workshops were often the single least helpful bit of feedback, impinging upon the vaporous whorls of suspense and necessary reserve that are integral to good storytelling, no matter the form.

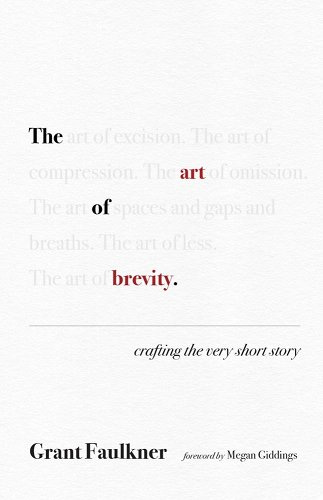

I’d trained myself to write through backstories, layers of details, and thickets of connections, but the more I pared my prose to reach 100 words, a different kind of storytelling presented itself. The art of brevity. The art of excision. The art of compression. The art of omission. The art of spaces and gaps and breaths. The art of less.

Such an art finds itself at the center of flash fiction, which is defined as a story under a thousand words and goes by many names, including “short-shorts,” “miniatures,” “sudden fiction,” “hint fiction,” “postcard fiction,” and “post-it fiction,” among others.

Flash communicates via caesuras and crevices. There is no asking more, no premise of comprehensiveness, because flash fiction is a form that privileges excision over agglomeration, adhering more than any other narrative form to Ernest Hemingway’s famous iceberg dictum: only show the top one-eighth of your story and leave the rest below water to be conjured. A one-hundred-word story might only show the top 1 percent of your story.

Flash is a form that naturally holds transience.

Flash is a type of border crossing into a different land of storytelling, especially the “short-shorts” of the world of microfiction (stories less than four hundred words).

For one, flash is a form that naturally holds transience. Julio Ortega says in the flash series he calls Diario imaginario that he prefers to write them with cheap hotel pens because of the feeling of “provisional, momentary writing.” The writer Leesa Cross-Smith says flash stories “are here and they are gone . . . we’re talking not much room for backstory, we’re talking drive-thru stories and quickies and pit stops and sneaky, stolen kisses and breathless sprints and gotta go.” In his fifty-two-word story “Lint,” Richard Brautigan ponders the events of his childhood and compares them to lint, “pieces of a distant life that have no form or meaning.”

Except that by capturing these small, intense moments we’re elevating the lint-like stories of our lives into something much more. The flash form speaks to the singularity of such stray moments by calling attention to the spectral blank spaces around them. Flash allows stories to capture the running water of the everyday. Suddenly, the strain of music heard faintly from the next apartment becomes the reason for a story itself.

Brevity allows us to get close to the unsayable, to know something that is beyond words or the wordless moments words bring us to. The aesthetic of brevity helps return us to direct sensation. It heightens attention, recasting life with vividness. We realize the contradictory significance of things. Or the harmonious significance of things. Or both.

It’s a little like falling in love. It’s a little like noticing the first slant of the autumn sun. It’s a little like that moment of waking from a powerful dream and finding yourself in real life.

But … back to the magic of happenstance.

One thing led to the next. I developed a passion for 100-word stories and started 100 Word Story with my friends Lynn Mundell and Beret Olsen. I became addicted to writing 100-word stories, so I wrote Fissures, a collection of 100-word stories. And now I’ve written The Art of Brevity, which comes out next month.

I’ve decided to publish excerpts, quotes, and exercises from the book in this newsletter in the coming weeks to create a conversation around brevity. I hope you’ll buy the book. I hope you’ll try your hand at this short form. I hope you’ll contribute to the conversation about the aesthetic of brevity.

Because a quote on brevity

“I usually compare the novel to a mammal, be it wild as a tiger or tame as a cow; the short story to a bird or a fish; the microstory to an insect (iridescent in the best cases).”

—Luisa Valenzuela

Because an exercise in the art of brevity

One definition of craft is that it’s the contours of a story. That's true, but I also think craft is how we want to touch a reader. We write mainly through a sensibility, so our sensibility is as important as any plot or characterization tip.

In writing flash, I think often of Roland Barthes’s question in Pleasure of the Text: “Is not the most erotic portion of the body where the garment gapes?” It’s an apt metaphor for flash fiction because these tiny stories flow from tantalizing glimpses that lure the reader forward.

That's why I started this book with the chapter “Thirteen Ways of Looking at Flash Fiction” (which I originally published in Lit Hub). To write flash, you’ll likely need your words to sprout in a different-sized pot, so it’s good to visualize a narrative with different metaphors in mind. The metaphor represents your sensibility, the feel for your craft.

So the first exercise for you is to choose your metaphor for a short-short. Check out some of the ones I listed in the Lit Hub article to get you thinking.

Because here’s one of my 100-word stories

The Toad

Flattened by a car, its arms spread out, a little like Jesus. The sun had baked it as crisp as a potato chip.

“Poor toad,” Maria said. “Didn’t know how to cross the road.”

“Maybe he thought the car was a new friend,” I said. “Rushing to greet him.”

“Or he was puzzling how such a small thing in the distance could become so large.”

We spent hours in such conversations. It was nice, how we never talked about what was next, who we were together. As if the toad wasn’t part of every story in its way, even ours.

Because I’d love for you to buy one of my books

I write this newsletter for many reasons, but mainly just for the joy of being read and having conversations with readers. This newsletter is free, and I want it to always be free, so the best way to support my work is to buy my books or hire me to speak.

Because more about me

I am the executive director of National Novel Writing Month, the co-founder of 100 Word Story, and an Executive Producer of the upcoming TV show America’s Next Great Author. I am the author of a bunch of books and the co-host of the podcast Write-minded.

My essays on creative writing have appeared in The New York Times, Poets & Writers, Lit Hub, Writer’s Digest, and The Writer.

For more, go to grantfaulkner.com, or follow me on Twitter or Instagram.

I’ll give micro a go. Why not? Sounds fun!

Thank you for including "The Toad" as an example of a 100 word story. I didn't realize until I saw the story on the page that 100 words is really really short! Also, the story held so much in its tiny container.