One of the questions I hear most often from writers is how to write a good ending. Hemingway said he wrote 39 different endings to A Farewell to Arms, and I know that most writers have reckoned with nearly as many endings to a story at some point in their writing life, no matter if it’s a novel or a short story.

To explore the question, I offer an excerpt from the chapter on endings from my book, The Art of Brevity.

How to end?

In such a short form, I always say you’ve got to nail the ending like a gymnast. If you waver, tip, or fall, you’ll ruin everything you’ve previously achieved.

It’s akin to the punch line of a joke: one extra word, one extra pause, and the punch line doesn’t work quite as well. The rhythm has to be perfect.

But there are so many different ways to define how to nail the ending, and as strange as it is to say, stories often resist endings, or writers create too much of an ending. It’s interesting how in the attempt to write a good ending, we keep going further, writing more.

I was once told that the best way to end a story is to end it two paragraphs earlier, so I always look at my endings and see how they read if a substantial chunk of them is taken away. I find it’s as true as any writing advice I’ve ever received.

The worst ending, at least for me, is one that forces a twist upon the story—a supposedly clever paradox, an odd coincidence that fails to illuminate or truly reveal anything. Is simple surprise the goal of an ending? If that’s the case, then the story whose purpose is the punch line or twist at the end functions like someone flicking off your cap as you walk down the hallway.

I suppose such endings are spawned by the idea that an ending must hold a dramatic reversal, which has always seemed overrated to me. I see too many writers ruin their stories with such overreaching when a subtle reversal, a nuanced recognition is preferable.

Charles Baxter advises writers to pursue a discovery at the end that is an “emergent precious thing.” That fits my definition of a good ending because it is a search for a culminating poetry.

Perhaps poets know more about endings. “The love of form is a love of endings,” wrote the poet Louise Glück, and, indeed, since writing a short-short places the writer in a keen attunement with form—rather than the rambling spirals that a novel might have—the ending becomes more palpable, more pronounced, more of a key and deciding ingredient. Poetry also is keenly tuned to an ending that relies on association.

A short-short’s ending is certainly different than a longer work’s because it can be grasped as a whole, in a moment, like a poem, so it resonates differently.

One reason to study haiku is because of the associative leap that tends to happen between the second and third line. That leap travels through the ending, an unfinished breath.

David Shields thinks an ending should provide “retrospective redefinition,” like the couplet at the end of a sonnet that turns the poem in a new direction—it should make the reader view the story they have just read in a new light that requires them to think of it differently.

George Saunders says he once defined the ending as “stopping without sucking.” His premise was that a writer should charm and interest the reader throughout the story, so the story is continually escalating until the very end. “If, at one such moment, we stop, we at least can say that we didn’t bore anybody,” said Saunders.

I like the writer Jayne Anne Phillips’s definition for the ending of a short-short. She said that the last lines of a short-short “should create a silence, a white space in which the reader breathes. The story enters that breath, and continues.”

Yes.

Because a prompt for endings

Take one of your stories and see how the resonance of the ending changes if you end it a couple of paragraphs earlier. What can you gain by suggestion, by indeterminacy?

Think of Valeria Luiselli’s take on endings: “The end of things, the real end, is never a neat turn of the screw, never a door that is suddenly shut, but more like an atmospheric change, clouds that slowly gather— more a whimper than a bang.”

Because a quote

Martha Graham’s advice to a younger choreographer: “There is a vitality, a life force, an energy, a quickening that is translated through you into action, and because there is only one of you in all of time, this expression is unique. And if you block it, it will never exist through any other medium and it will be lost. The world will not have it.”

Because I’m teaching an online course (10% discount!)

My course on novel writing just launched with Domestika!

If you use this code, you'll get a 10% discount: GRANTFAULKNER-PROMO

A testimonial!

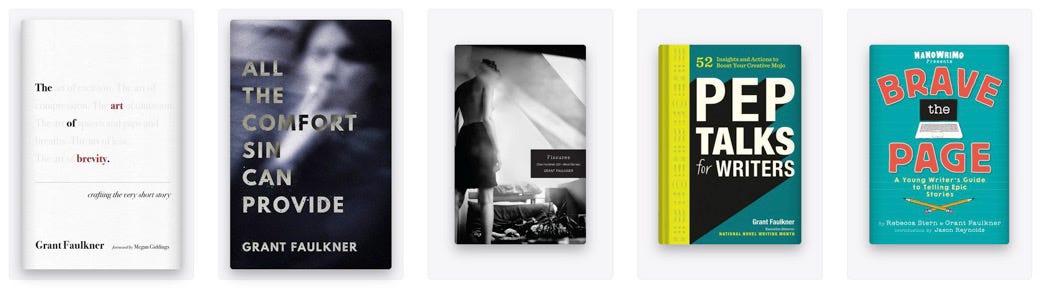

Because I’d love you to read one of my books

I write this newsletter for many reasons, but mainly just for the joy of being read and having conversations with readers. This newsletter is free, and I want it to always be free, so the best way to support my work is to buy my books or hire me to speak.

I love Jayne Anne Phillips’s definition of an ending. It can be easy to let yourself fall into a surprise ending. I've found poetry, as you mentioned, to be a great help in writing fiction, especially short stories. I think many writers overlook poetry.

Hey Grant, some valuable insights here. Given the topic, I feel justified in plugging a Substack post I did on trying to get into the, er, zone of writing, to which you might relate. Anyway, keep it up.