The Art of Splitting Apart

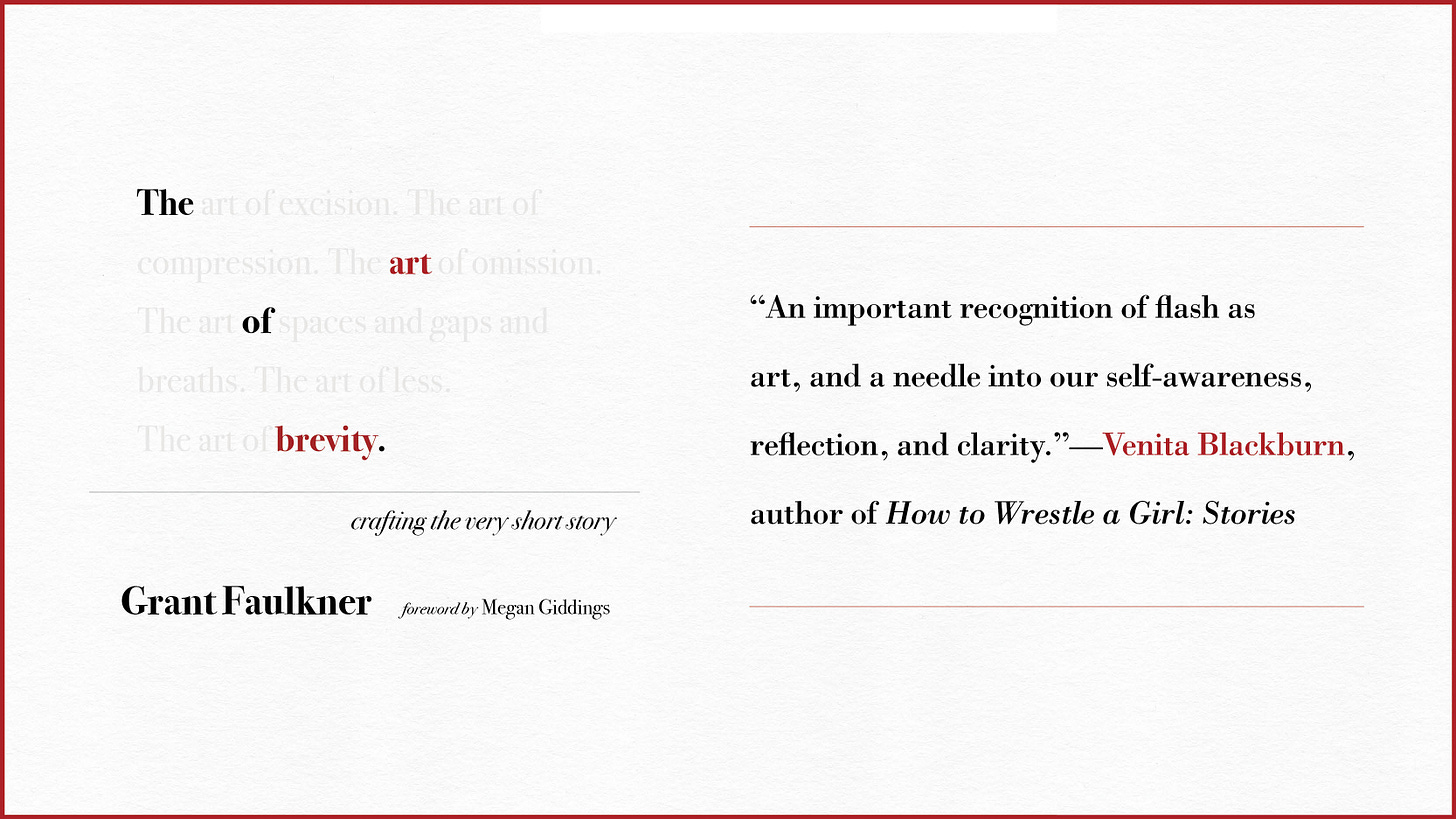

I’ve been thinking about my love affair with the fragment this week as I get ready for the launch of my book, The Art of Brevity.

I don’t think of life as a round, complete circle—it’s shaped by fragments, shards, and pinpricks. It’s a collage of snapshots, a collection of the unspoken, an attic full of situations that aren’t easily disposed of. The brevity of flash is perfect for capturing the small but telling moments when life pivots (or splinters) almost unnoticeably, yet profoundly.

I am fascinated by the disconnections in my life, whether it’s the gulf between a loved one, the natural world, or God. I don’t want a form that represents comprehensiveness or unity because that’s an aesthetic at odds with my experience of life. In fact, our universe is becoming more entropic as I type.

To write in fragments calls on a different sensibility, a different tactile feel, a different artistry.

Each moment on the page is a brush, a kiss, a reaching out.

“So many fragments, so many beginnings, so many pleasures,” Roland Barthes wrote. He understood the seductive nature of a fragment. It’s a wink of the eye, a revelation, a promise. In fragmentary, ambulatory texts, the reader is less involved with a pathway of narrative construction than a series of impressions that open up. Meaning does not give itself as a whole; it lies in the gradual unfolding of signs.

To write this way, as Barthes suggests, is to write with a sense of initial attraction and flirtation, to write always in the erotics of the moment. I use the word erotics because I think of fragments as a series of “touches” on the page. Each moment on the page is a brush, a kiss, a reaching out.

If you line fragments up, Barthes wrote, they become part of a song cycle, “each piece self-sufficient, and yet it is never anything but the interstice of its neighbors.” The fragment, like the haiku, implies an immediate delight. “It is a fantasy of discourse, a gaping of desire,” he wrote.

The appeal of a fragmentary style of writing isn’t just aesthetic for Barthes; it is existential. He preferred a form that militated against mastery and authority, one that didn’t adhere to a fiction of comprehensiveness and finality. Language and structure for Barthes were always matters of unveiling and discovery, so he favored a language that produced uncertainty and difference, a language that was flexible and didn’t seek to rule and determine, but to open.

Coherence can only be felt in the moment, and it’s fleeting. Fragmentation supports a view of the world as shattered, pixelated, and momentary. Nothing is fixed, not even time or space, and this imbues life with a looseness, an indefiniteness that weakens certainty or the solid assertion of rules and morality. Life feels more arbitrary in such a narrative. The rondure of experience is no longer so round. Time is out of joint.

Writing with the fragment invites in the question of betweenness. A fragment has edges, cracks, seams, and sutures. By being broken apart, it possesses new boundaries, existing in a liminal state. The form invites an exploration of a situation that lives in between different states of life.

The glint of understanding flash fiction proffers is humble by definition. Writing with a fragmentary sensibility is a style of writing that is mistrustful of declarations of truth, preferring images, fantasies, and reverie. In fact, for Barthes, language resembled the shuffling of a kaleidoscope, inviting appreciation of its superficial effects.

Barthes recommended reading with “jouissance”—to read with attentiveness to a text’s edges, its gaps, its verticality, its crests—to read “in accordance with pleasure.”

“Like the caress, language here remains on the surface of things; the surface is its realm,” he wrote. Objects and words become the equivalent of cutups, a world that requires us to explain it by unfolding its surfaces, unpicking the “stitched squares” of its “rhapsodic quilt.”

In celebration of the launch of my book, The Art of Brevity, I offer this rhapsodic quilt of quotes from the book to celebrate the fragment.

Because a story should haunt

“I like to deal with fragments. Because no matter what the thought would be if it were fully worked out, it wouldn’t be as good as the suggestion of a thought that the space gives you. Nothing fully worked out could be so arresting, spooky.”

—ANNE CARSON

Because at the center, what?

“To write in fragments is to place stones around the perimeter of a circle. I spread myself around: my whole little universe in crumbs; at the center, what?”

—ROLAND BARTHES

Because an incomplete picture is more realistic

“Any complete picture is an illusion. … A picture that seems less complete may seem less of an illusion, therefore paradoxically more realistic.”

—LYDIA DAVIS

Because of the stories in the margins

“Flash gives voice to stories in the margins, the ones deemed too slight or elusive for more conventional narrative modes. And the deeper I get into the practice of writing, the more I am drawn to this interstitial space: between sense and scene, snapshot and story, silence and sound. By illuminating the underseen, we reveal a world more fully realized, in which small gestures resemble events, and a single moment can carry the weight of years.”

—RAVI MANGLA

Because we arrange the air

A book that is made up of fragments. … There is white space, therefore. Ghosts coming and going, adding and subtracting, rearranging the air.

—J.D. D’AGATA

Because chaos. And order.

“The artist confronts chaos. The whole thing of art is, how do you organize chaos?”

—ROMARE BEARDEN

Because upcoming events

Specific dates and times still coming for some events.

Feb. 16: Book Launch: Pegasus Books Downtown (in conversation with Lynn Mundell, co-founder of 100 Word Story)

Feb. 17: San Francisco Writers Conference

Feb. 21: Green Apple on 9th (in conversation with Melanie Abrams)

Feb. 26: Lit Camp Workshop

March 8-11: Associated Writing Programs Conference

March 22-26: Storyfort

April 20: Kepler's Books

May 6-7: Bay Area Book Festival

Because more about me

I am the executive director of National Novel Writing Month, the co-founder of 100 Word Story, and an Executive Producer of the upcoming TV show America’s Next Great Author. I am the author of a bunch of books and the co-host of the podcast Write-minded.

My essays on creative writing have appeared in The New York Times, Poets & Writers, Lit Hub, Writer’s Digest, and The Writer.

For more, go to grantfaulkner.com, or follow me on Twitter or Instagram.