One of our most basic human needs is the desire to be understood.

There are few things more frustrating than being misunderstood—then trying to clarify things—but often becoming even more misunderstood—and trying and trying to be heard and seen properly—through emails and texts and phone calls and discussions and … pick your favorite style of dramatic display.

I don’t know why we have such a deep and powerful need to be understood—why it’s so maddening to be mischaracterized or unseen—but I know it’s a central driver of why we write. Why we explore words and string them together and hope they convey our truth.

We don’t see pigeons or squirrels or elk getting frustrated for being misunderstood. That’s because they don’t have language. A language that promises to deliver a mirror to the world, a mirror to the soul, but a language that has imprecision embedded in it (so misunderstanding is naturally a part of understanding and vice versa).

Our words are just signifiers, and as useful and even as magical as those signifiers can be, they often fail us. Or they’re often only part of the story. Because a story is sometimes bigger than its words—or a story whispers around its words, takes form in what is felt but not seen. Bread crumbs that disappear. The echo of an echo.

I’m thinking about this because Ingrid Rojas Contreras was recently on my podcast Write-minded to talk about her memoir, The Man Who Could Move Clouds, and she talked about how her ability to write the book began with the amnesia she experienced after having a bike accident and how that amnesia was a different kind of portal into understanding the world.

“There's room in language to be without language. When I was without a memory, it triggered the question, if you're someone who loves language, then what is it like to not have language and be outside of it? Are there different ways of languaging? The languaging where you are without language is definitely for me one of the more interesting parts, as opposed to the project of cataloging or being sure about what we’re saying exactly and pinning it down.”

Different ways of “languaging”

I’m fixated on how language strives for surety and fails. How we as writers by definition strive “to pin it down,” yet pinning it down is only one function of language.

There are also the “different ways of languaging”—ways that tend to be part of uncertainty, ambiguity—words that evoke the unstable or shifting parts of perception, the hazy territory of existence that is difficult to put into words, difficult to understand.

And sometimes we need to lose language to gain language. Of her amnesia, Ingrid said, “Losing my memory was ground zero because it was almost like an unadulterated way to recall and understand everything again. I really wanted to write this book as a way to make my own mirror.”

To make a mirror, to be seen, to be understood.

Language is unlanguaging. And in unlanguaging is language.

It’s interesting because a big part of being understood for Ingrid is capturing the intertwining of the more mystical and magical parts of life and braiding them with “reality.”

Ingrid enlightened me about the label of “magical realism.” She views it as an inaccurate label foisted on Latin American stories by Western culture makers, book marketers (colonizers, in short) that otherizes and exoticizes and even invalidates world views that are indigenously rooted. She speaks to the tension between the ways first people tell and see stories and the way those stories are characterized by those on the outside.

“With this memoir, I wanted to correct that notion, to say that it’s not that the stories in this book, and the stories of many Latine people, resemble magical realism; it’s actually the other way around—magical realism resembles our lives.”

Language is unlanguaging. And in unlanguaging is language.

It’s interesting because Ingrid said she thinks of her stories in Spanish and then translates them into English in writing, so words and all of the touches and nuances and wisps of words are part of her approach. She says her words are English on the surface but Spanish in the structure.

I loved listening to Ingrid talk about her creative process because she speaks like a poet, a mystic, a searcher, a linguist, and more. She rubs words in her hands and practices “listening to the air for the answer” as part of her creative process.

I’ll leave you with a writing tip that goes with this approach—so you don’t have to get amnesia. Ingrid gave this advice about writing a memoir (but it applies to fiction as well):

“When you’re listening to a story at a family or chosen-family gathering, become a student of structure and tone … What silences are kept? What silences are broken? Surveying all that land can teach you so much about what to write about, and how to do it.”

Listen to Ingrid Rojas Contreras on Write-minded

Because a quote

“There is another world, but it is in this one.”

~ Paul Eluard

I think this is part of “unlanguaging”—the other world in this one eludes language, exists in between words, beyond words. Yet we search to tell about this other world in words.

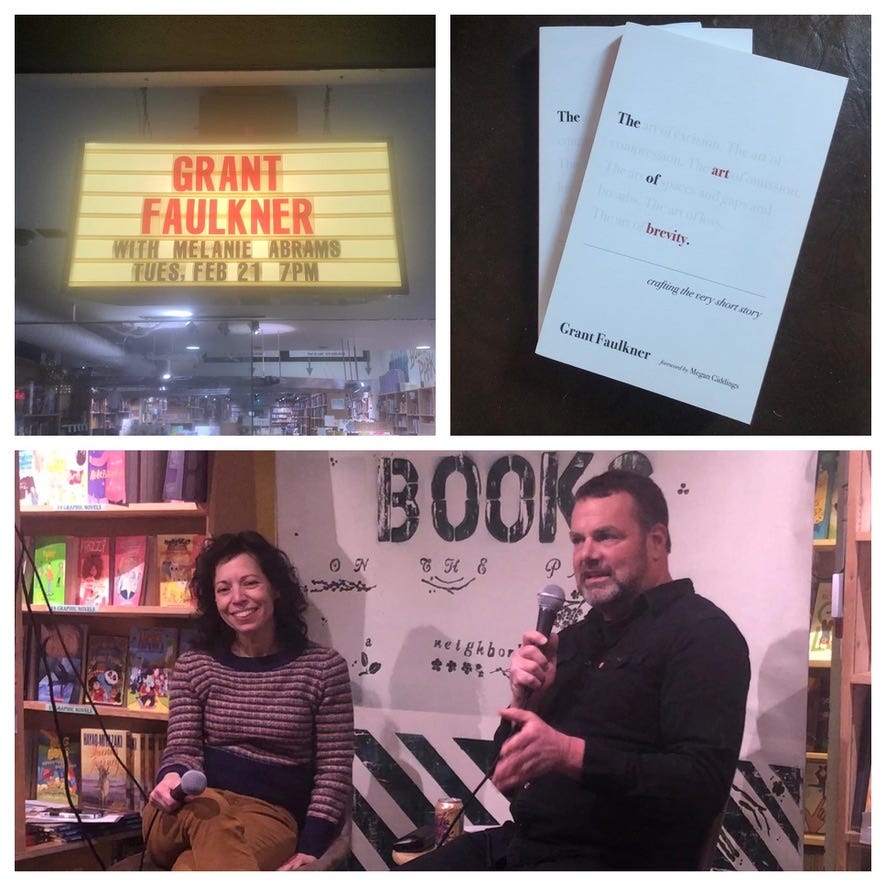

Because it’s my book’s birthday!

I'm throwing a little celebration for the one-year anniversary of my book, The Art of Brevity. It's been so much fun teaching workshops across the country and talking to so many writers (the side benefit is how many wonderful flash stories I get to read).

I look forward to another year of going deep into brevity, so ... let me know if your writing group is reading this book, and I'll see if I can Zoom by.

I once spent six months without language as a deconditioning exercise. No music with words, no reading, no media, no conversation, just me in a lovely rented cabin in the Berkshires.

I viewed it as an experiment to reboot my mind. I noticed an increased ability to conceptualize without words. Changed my life.

This is fascinating. I listen to podcasts, books, music while I paint-- my waking moments are crowded with language. All of this listening is for my own "education" but rethinking what education is.