Like many, I’m obsessed with the TV show The Bear, an FX show about a frenetic, struggling Chicago sandwich shop that Carmy Berzatto inherits from his brother, Michael, who has committed suicide.

After three seasons, I just realized that the reason I’m so into the show is because of the many ways it is an exploration of the creative life (see my list below).

It’s about trauma. It’s about pushing creative boundaries. It’s about addiction. It’s about love. It’s about striving. It’s about community. It’s about food and nourishment (and non-nourishment). It’s about being in service to others. And out of service.

Carmy has left his career as an award-winning chef to try to fix things at the restaurant. Note: that word fix plays large in the show. There are things to fix beyond the restaurant, forcing viewers to ask how fixing the restaurant mixes with fixing yourself, fixing your history, fixing your family—and then whether fixing is even possible.

While a lot of critics and viewers disparaged the most recent season, Season 3, for its lack of a guiding narrative arc or true character development, my obsession has only grown because I think they’re viewing the show through the wrong lens. The Bear isn’t a conventional series with hooks in each episode to get you to keep watching. It’s not about narrative resolution or satisfaction. It’s an immersion into a state of being, and an often painful state of being at that.

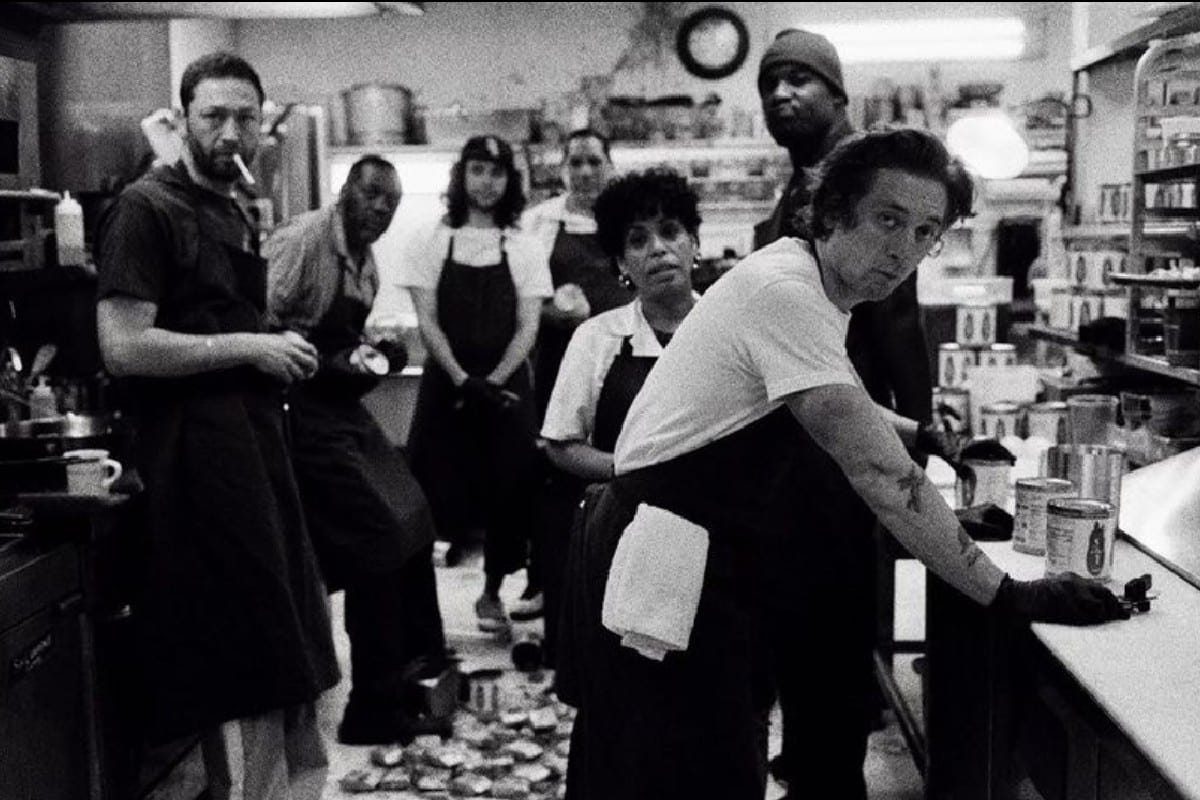

That state of being is best illustrated by the hectic madness of the kitchen. The kitchen operates as a metaphor for how we make art in the world, and how we live life while making art, and how the two things often don’t go together gracefully. Every character is a creator of some type, so the show has evolved into an exploration of how we answer the call to be creative in life.

We know that if Carmy doesn’t change, his hustle is a suicide pact.

Carmy aspires to the highest of the high art of cooking, but his striving is fueled by his pain—the pain of his brother’s death and the pain of being raised by an alcoholic mother and an absent father. He’s become a depressed, anxious workaholic who can barely smile (the family’s dysfunction is brilliantly captured in the chaotic Christmas episode in Season 2, one of the best single episodes in TV history).

In the course of the first three seasons, the restaurant goes from being The Beef, a hole-in-the-wall fighting just to exist, to The Bear, a fancy restaurant aiming for a Michelin star rating—yet still struggling to exist.

Everyone is in survival mode all the time. The kitchen is loud, contentious, full of frictions, yet it’s also full of aspirations, dreams, and togetherness. It’s at once a damning portrait of the personal and professional toxicity that swarms around us when we’re forced to relentlessly hustle—while also being a celebratory portrait of pushing the boundaries to create something sublime.

Because the show is as interested in exploring a state of being as it is a storyline, and because the show is interested in trauma, it’s often fundamentally unpleasant to watch. It intentionally risks alienating viewers to delve into all types of friction—as if it’s a John Cassavetes movie and not a streaming series.

For example, we leave Season 2 with Carmy melting down while he’s accidentally locked in the walk-in fridge, and he inadvertently says things in his frustration that basically kills his girlfriend Claire’s love for him, who stands outside the fridge listening, unbeknownst to him.

Claire is like a beacon of light in the show, offering a love that transcends all of the dysfunction that clamors around the characters. There’s really nothing more we want as viewers than to see them get back together, and most shows would resolve their split in the next season, but in The Bear they don’t even talk in Season 3.

We live in Carmy’s self-sabotaging pain for the entire season, and we live in the way that pain drives his art, except it doesn’t even feel like art. It just feels twisted and wrong.

I don’t know if we’ll ever get the viewer satisfaction of seeing them get together, but I’m fine if we don’t because life is largely about irresolution, and it takes a bold artist to go there.

Here are some of the themes of creativity I’ve gleaned from The Bear.

11 lessons of creativity in The Bear

Our pain can drive our art. “Trying to fix the restaurant was me trying to fix whatever was happening with my brother,” Carmy says. Pain forms our artistic materials. We try to shape our pain into something sublime and transformative. There’s no guarantee our art will heal us—but our pain can drive us to try to understand it through our art.

We’re at our best when we’re one with our people. At his best, Carmy knows his brilliance or determination isn’t enough. He hires Sydney, and things in the restaurant work best when Sydney and Carmy are working together (and caring for each other). Sydney respects Carmy but also isn't afraid to show Carmy his place when he treats her poorly. Lesson: an incredible talent does not give a person license to treat people badly.

Work with a higher purpose. The Bear is filled with mayhem and fighting, but at the center of it are people who want to feed other people more than anything else in the world. That purpose drives their creativity and their work.

Success requires relentless discipline. The most admirable trait in Carmy is his discipline, sheer hard work, and consistency, which is a lesson he tries to teach his chefs at The Beef by setting up his Brigade.

But extreme discipline can be your ruin. Carmy is also a joyless workaholic who is largely alienated by life and doesn’t know how to enjoy himself because he’s so caught up in his pursuit of excellence. Should you sacrifice this much for your art?

Look in odd places for your art. Marcus represents a healthier, more playful creativity than Carmy, which is perfectly shown when he searches to make the perfect donut. Marcus is the character who has the most curiosity.

Your demons will haunt you (relentlessly, and perhaps forever). When Carmy worked at New York's Eleven Madison Park, he suffered torturous verbal abuse from a chef played by Community's Joel McHale. McHale is the embodiment of the most evil and damning Inner Critic. Carmy has PTSD from McHale’s taunts.

You’ll feel like burning it all down. Carmy confesses to Marcus that he sometimes thinks about burning it all down after Marcus messes up one time. It’s his way of showing Marcus there are times when it is going to be overwhelming.

Find belonging with the weird ones. There is strangely a lot of affection and belonging that takes shape in all the yelling in The Bear. Anyone who has worked in a restaurant will understand this. Anyone who is an artist also understands that the most troublesome people are often the most enlivening.

Art should be nourishing. The show is one part tour of other chefs and their restaurants, and in presenting their mentorship to Carmy, there is a constant refrain of how their satisfaction comes from being in service to others, to nourish.

Ambition is good for the soul. For all of the shittiness of work, its abject humiliation, there is a strange redemption in pushing boundaries higher, to create a new and better dish, a new and better experience. The best exemplification of this is when the tragically hopeless Richie starts coming into his own when Carmy sends him to stage at the esteemed restaurant Ever with chef Terry (Olivia Colman), where he finally learns about his strengths by working in service to others.

And yet … the eternal question of making art

Still, there’s the question of the toll of the hustle required to make art and make it at a high standard. In one of the final scenes, at the going away party for Ever, Terry tells Carmy how she’s giving it all up simply because she wants to live a life without the hustle—to live peacefully.

Carmy remarks on how unlikely it is that the high art of a gourmet restaurant happens because the hustle is so grinding. And we know that if Carmy doesn’t change, his hustle is a suicide pact.

It’s a question we all must ask ourselves as artists: whether the tireless hustle is worth it. We tend to sacrifice the delights Terry is opening her life to in order to make our art.

We loved excess. And we loved loving excess together.

Perhaps the message of the show is that we fix some things, and some things get broken in the fixing, and sometimes we don’t even know what to fix or how to fix it. Maybe, like Carmy, we give up smoking but endlessly pop nicotine gum in our mouths. Maybe our intention to be healthy doesn’t make it even a step forward, if that, but then maybe it’s lifting your foot to take the step that we have to celebrate. Because we won’t get it all.

I worked in restaurants for a decade. All of them were variations of The Bear. I worked shifts that burned the life out of me. I met the craziest and most wonderfully alive people.

My favorite moment was closing time, when we poured ourselves beers, turned the music up loud, stacked the chairs on the tables, mopped the floors, and eased our weary bodies and souls into the darkness of the night. We did everything to excess. We loved excess. And we loved loving excess together.

That moment at closing time brought on a peace that only exhaustion can bring. That moment, once each day, was ours and ours alone. We sunk into our comforts. We became human again.

But then we’d be back the next day, and the craziness would ensue again.

Because a quote

“You can always tell when a person has worked in a restaurant. There's an empathy that can only be cultivated by those who've stood between a hungry mouth and a $28 pork chop, a special understanding of the way a bunch of motley misfits can be a family.

“Service industry work develops the soft skills recruiters talk about on LinkedIn— discipline, promptness, the ability to absorb criticism, and most important, how to read people like a book. The work is thankless and fun and messy, and the world would be a kinder place if more people tried it. With all due respect to my former professors, I've long believed I gained more knowledge in kitchens, bars, and dining rooms than any college could even hold."

—Anthony Bourdain

Join me for an amazing writers’ conference

The Okoboji Writers’ Retreat is one of my favorite writing events. It’s its own kind of unique. Take it from participant Suzanne O'Dea:

“The setting is gorgeous; the speakers are more accessible than at any of the many writers' retreats I have attended over the years. While it is a brash statement, I will make it anyway: the speakers are the most knowledgeable and the best communicators I have encountered.”

Here’s a link for a $100 discount! Join me this Sept. 22-25.

I forgot one thing in my list above. Asking for help. Carmy doesn't know how to call Claire. He either doesn't have access to his words, or he doesn't know how to form them, or he's decided to pave them over with the discipline of his art.

But he clearly needs to ask for help, in a bunch of ways. So self-reliance and discipline and hard work are all double-edged swords in the show. The more we ask for help, the better we and our art will be.

My favorite scene of the series is Carmie at an Alanon meeting. Just his face. He’s such a talented actor, and he captured that moment when you walk into a room, and you suddenly feel understood, or that there is hope, that there are other people in the world who might be experiencing the intense pain that you are experiencing, and somehow that makes it a little better. I think the show is exceptional. And yet I’m struggling with season three. It’s not that I need the narrative arc or resolution. I do feel the writers have lean too heavily on conflict as a means of communication. The nonstop yelling in some of the episodes in season three instead of being intense or exciting are just kind of tiresome for me. I want them to stop yelling and talk to each other. I do still think it’s an amazing show overall. I love the lessons on creativity you take from the show. Great post.