Each week until the end of National Novel Writing Month in November, I’m going to write about a different creativity topic related to how to succeed in NaNoWriMo. If you’re not doing NaNoWriMo, don’t worry: all of the topics should relate to any creative project.

Here are the first pieces in the series:

The joy of writing for me is in large part the joy of exploring (and even inhabiting) another character.

The degree of our passion for the characters in our stories, whether we love them or hate them, fuels the vigor of our writing and the depth of our commitment.

The best characters are full of mysteries, nuances, peculiarities, and contradictions. You never know where they’ll lead you, which is why they’re so compelling. Like the best people, they make life a surprise.

I just interviewed Angie Cruz for my Write-minded podcast, and she told an interesting story about her novel Dominicana, which took her 14 years to write. The novel had met with numerous rejections, even though she’d already published two celebrated novels, and she’d actually given up on it numerous times.

During one of those times, she listened to a YouTube clip of a friend doing karaoke, and she wondered why she’d never done karaoke, and then she wondered why she considered herself a bad singer. She took voice lessons, discovered she wasn’t a bad singer, and this process led her to unlock the key to an antagonist in her story—to give her a beautiful voice.

Angie wrote against the grain of a character in order to bring her to life.

On another episode of Write-minded with A.M. Homes—one dedicated to characterization—A.M. provides a type of master class, starting with her mentor/teacher, Grace Paley, who taught her that the key to good characterization is to write the truth according to the character, not the truth from your viewpoint.

This is challenging to do because most of us are self-oriented creatures who have a hard time imagining that others don’t see the world as we do.

In order to better inhabit a character, A.M. interviews her characters. She covers everything from what kind of toothpaste they use (if it reveals something crucial about who they are) to their socioeconomic background.

The key thing: she only uses character background info if it’s relevant to the drama of the story.

Here are some interview tools I’ve played with:

The Proust Questionnaire: The Proust Questionnaire is a set of questions, created by the French writer Marcel Proust. Proust answered the questionnaire in a confession album—a form of parlor game popular among Victorians. It later went on to famously become a Vanity Fair feature.

The 36 Questions that Lead to Love: These questions, popularized by The New York Times “Modern Love” column, come from a study that explores whether intimacy between two strangers can be accelerated by having them ask each other a specific series of personal questions.

The thing is to not make your characters in the mold of yourself but to go deep into their peculiarities and differences. Our differences make life a rich and nuanced affair. They create the frissons (and frustrations) of drama we wake up to each day, the mysteries we wend through.

The shorthand for characterization is character = desire, but if you’re going to write complicated characters with nuance and depth, you need to go beyond their desire.

Some people like to talk a lot. When they walk into a room, any room, they start rattling off all kinds of opinions, jokes, stories. They laugh, they smile, they bellow, they snort. They’d start singing old Elvis songs if asked, and they might even do so unbidden.

And then there are those who practically have magic powers of invisibility. They live in a realm of quietude, seeking it out and creating it. They know the corners of rooms well. They enter and exit parties with scarcely anyone noticing. If you gave them a convertible sports car, they’d donate it to a charity before taking it for a test drive.

The wonderful thing is that as author you get to be an omniscient God, a psychologist, a friend, and a judge. You get to be the priest who hears your characters’ confessions and the devil who whispers in your characters’ ears to do the wrong thing. You get to immerse yourself in what I think of as a character kaleidoscope: turn the tube of your story, and the colored shapes of your characters tumble into different colors and patterns.

That’s our job as writers—to explore behavior in the shaky and shifting terrain of the world. Even though everyone looks somewhat similar—two ears, two eyes, a head, a belly button, and so on—everyone behaves differently. We’re animated by conflicting impulses, striving for noble purposes, yet often acting in ignoble ways.

When I conceive of a character, I think of the fundamental questions that are the catalysts for any story: What does my character yearn for? What does my character lack? What obstacles lie in my character’s path? Does my character prefer to live according to the familiarity of a strict routine, or do they constantly seek out new experiences? Does my character trust people and open up to new people, or does my character view them warily and assume the worst of others?

And then what happens when life heats up in intensity or fractures with unpredictability? If my character, who is introverted, disagreeable, and doesn’t trust others is trapped in a sunken ocean liner with an odd cast of travelers, as in The Poseidon Adventure, will he or she work with the group to survive or go off alone? Will my character’s natural distrust contribute to survival or lead to demise?

Drama occurs when a person is not quite themselves, when they’re seeking something new, or when a situation pressures their defining traits.

Drama also occurs through simple perception—or misperception. One of the rich paradoxes of life is that we strive to know the world with certainty, and we think we perceive it clearly through our senses, but we actually live through unsettled perspectives, changing stories, a veritable phantasmagoria of perception, no matter how sure we are of what we’ve experienced.

Consider this: two people at the scene of a crime, watching the exact same sequence of events, often see things differently. We think of our sight as an infallible record of the world—a video recorder, in effect. But when we recall scenes in our mind, they become re-recorded—retold, in effect—so the story changes.

We don’t see what we see; we see what we think we see. Our memory takes in the gist of a scene, not its totality, and then the gaps are filled in during the retelling through the preexisting schemas, scripts, emotions, and hypotheses in our minds. We take reality to be true, but we form it through our beliefs, which form our perceptions, which then form our beliefs, and so on.

That’s why questioning by a lawyer can alter the witness’s testimony—the questions force a retelling, and the witness’s memory changes because of the new frame provided by the questioner.

We’ve all had these moments, when we remember something from the past completely differently from the people we experienced it with. We think we’re objective, but humans aren’t really wired to be objective. We make many errors in perception because of something caused by “confirmation bias”—our tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that confirms our preexisting beliefs or hypotheses rather than investigating our worlds in a neutral, objective way.

Everyone has experienced this at a holiday dinner when a clash of opinions arises. The tendency to privilege even the most minuscule fact that proves we’re right gets magnified as a disagreement gets more extreme and attitudes get polarized.

So why am I telling you all this? What does it have to do with writing? It’s because every character in your novel—every character in your life—passes through this mental juggernaut, seeking evidence of why their beliefs are right, weighing positive and negative perceptions. The shorthand for characterization is character = desire, but if you’re going to write complicated characters with nuance and depth, you need to go beyond their desire.

Therein lies the drama—the gap between expectations and reality, when two characters have a wholly different perception of the action. You get to look through others’ eyes, understand their thoughts, explore their perceptions and misperceptions, as if you’re looking through a kaleidoscopic mishmash.

Because NaNoWriMo Homework

Write a short narrative based on the next stranger you see. Use the interview tools listed above. Then explore how the stranger you’re writing about experienced the moment when you saw them. A person walking on the sidewalk is never just walking on the sidewalk. What might trigger a dramatic reaction? How will he or she or they react?

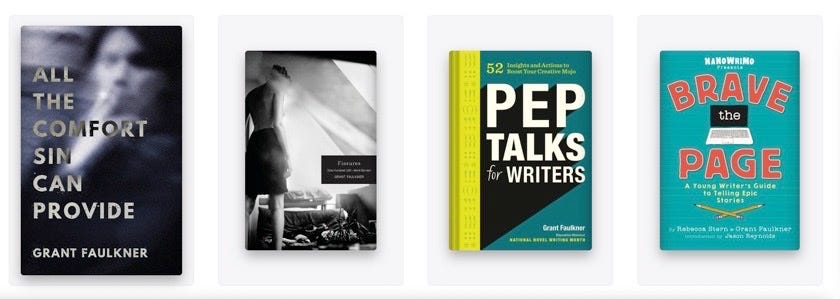

Because I’d love you to read one of my books

I write this newsletter for many reasons, but mainly just for the joy of being read and having conversations with readers. This newsletter is free, and I want it to always be free, so the best way to support my work is to buy my books or hire me to speak.

Because more about me

I am the executive director of National Novel Writing Month, the co-founder of 100 Word Story, and an Executive Producer of the upcoming TV show America’s Next Great Author. I am the author of a bunch of books and the co-host of the podcast Write-minded.

My essays on creative writing have appeared in The New York Times, Poets & Writers, Lit Hub, Writer’s Digest, and The Writer.

For more, go to grantfaulkner.com, or follow me on Twitter or Instagram.