Dear Readers,

There’s always the question: Do we find our stories or do our stories find us?

It’s a little of both for me. I’ve always thought my true calling was to be a junk collector, perhaps even more than being a writer. I was either a rag picker in a past life or I will be in my next. I love patinas of rust. I love ragged, torn clothing. I love finding abandoned items on the street. I save old plastic jewelry, torn-apart wrapping paper, and random shiny objects in a big box called my “collage box.”

Similarly, I keep a doc I call “stray phrases,” which is its own type of junk shop, a collection of odd sentences—stiff, voluptuous, rapturous, restrained, or just plain kooky, all of them special for a reason I likely can’t articulate. I just like them.

W. H. Auden described a poem as being written by connecting the best lines from his notebook, which mirrors the way I tend to write. Somewhere in the mix of having kids (and not having much time) and living in a state of perpetual transition—on buses and subways, standing around on playgrounds—I started carrying a notebook in my back pocket, which was a type of net to capture stray thoughts, overheard conversations, lines from a book I was reading.

My random jottings formed themselves into my creative process. The beauty of my jottings is that they don’t demand anything. In fact, they’re likely not to turn into anything (even those that are written with passionate ambition). But I type them up and either place them in my “stray phrases” doc or any number of other docs where I have works in various stages of dress and undress.

I like walking through my inner junk shop to look for odds and ends. That’s the perfect metaphor for the way I like to write, the way I like to think and live. The more forlorn and blemished the object, the more I want to burnish it by putting it in a story. I’d be perfectly happy living on the Island of Misfit Toys. I want to write a rhapsody of rags. Which is why I find a kinship with artists who open the possibilities of what can be found and turned into art, whether it’s visual art or a story.

Joseph Cornell was a storyteller who created narratives through bric-a-brac that he put together in boxes. He’d walk aimlessly through the streets of New York City, finding discarded treasures for his art: cork balls, metal springs, old photographs, dime-store trinkets, etc. His art was defined by the hunt for the unwanted, for insignificant detritus, which he then archived and reassembled to make new worlds.

He filled cardboard storage boxes with his found treasures and organized them in the basement of his mother’s house, where he lived, as if they were in a museum’s back room, each of them labeled. He attached the highest value to objects of little or no intrinsic worth. A box labeled “tinfoil” or “plastic shells” resided alongside another marked “Caravaggio, etc,” hinting at Cornell’s belief that great painters were no more important than the discarded objects of everyday life.

Cornell took these odd tools of his craft and made poetic “assemblages” or “shadow boxes,” known as “memory boxes” or “poetic theaters.” They were dream-like miniature tableaux that revealed tiny, magical worlds full of parakeets, Renaissance portraits, Victorian knick-knacks, maps. Cornell arranged the objects to create a story.

“A cursory glance at Cornell’s boxes could lead you to think that he was constructing reliquaries for coveted possessions, when in fact his talent lay in alchemising commonly discarded objects into a visually compelling state of being,” wrote Deborah Solomon, his biographer.

Cornell was famously reclusive. He never married or moved out of his mother’s house in Queens, and he rarely voyaged further than a subway ride into Manhattan, despite being besotted with the idea of foreign travel and obsessed with France. He created the shadow boxes to travel to new worlds, to escape through the motifs of birds, maps, and space. The boxes form themselves around a tension between freedom and constriction.

“My boxes are life’s experiences aesthetically expressed,” he said.

That’s increasingly how I see my writing: I pull boxes off the shelf in my “basement” and thumb through what’s collected to see what stories I might find.

Because I wrote a 100-word story on decay

This was the first essay we published in 100 Word Story, back in 2011, “On Decay.”

The menacing artistry of a rusted piece of tin, the pulse of its patina, incrustations. Sharp corners demand such sharpness. A shine requires work, exertion, planning, orders, but decay invites a slide into introspection, madness, abandonment, brilliance. The rebellion of the lost cause. Jagged brims threaten to claw. An eerie acquiescence. Abeyance. Disintegration an exhalation, like meditation. The lonely peace that can only be found in states of desuetude. So leave me alone, please, to enjoy the molds and rusts that find me. Let me tarnish and gaze upon my preferred russet shades. God is in the dust of remnants.

Because “rustscapes”

One of my favorite pandemic activities has been my daily walk, which doubles as a challenge to take a daily photo. It quickly became more and more challenging each day to find things I was interested in photographing, though, which forced me to notice the world in ways I might not have ordinarily.

I became very drawn to the myriad textures and patterns of rust, how rusted objects are like their own abstact art. Here are a few of my photos.

Because of the sheen of antiquity

“We do not dislike everything that shines, but we do prefer a pensive lustre to a shallow brilliance, a murky light that, whether in a stone or an artifact, bespeaks a sheen of antiquity. . . . we do love things that bear the marks of grime, soot, and weather, and we love the colours and the sheen that call to mind the past that made them.”

― Jun'ichirō Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows

Because a favorite word: desuetude

Each week, I’ve decided to include a favorite word in this newsletter. You might have noticed the word desuetude in my 100-word essay above. It’s a word that has great poetic allure for me, perhaps in part because of its French origins, the mere lyrical sound of it, but it simply means “a state of disuse, inactivity.”

But therein lies its beauty. Everything rusted is a story beginning. Abandonment creates its own aesthetic. The pensive lustre that goes with an old leather satchel or a tarnished watch. The sheen of age holds the layered nuances of a beauty that demands pause and reflection. To protect objects from weather is often to cheat them of their life, their potential. Grime and soot offer a different kind of polish. The tarnish of an object holds us because it returns us to newness and truth at the same time it introduces us to death.

I could probably spend the rest of my life taking photos of old barns sagging to the ground, worn fences, things collapsing. I love the beautiful grace that a patina musters in the face of demise.

Because a haiku

One of my heros is A.O. Dugas, a man of hats, a man of scarves, and a man of haikus.

Years ago, he started the “Daily Haiku Actual Postcard” project, in which he wrote a haiku and then sent it to a random person. He wrote and sent 1,001 haiku postcards by the end of the project. The photo below includes his last haiku, which he asked his mail carrier to pose with in homage to the postal service, without which the project would have been impossible.

Why do such a thing—just for the sake of writing, just to touch others, without the expectation of payment or maybe even a simple thanks?

Here’s what A.O. said:

"This project has many roots, but first and foremost I wanted to improve as a haiku poet. I'd already been doing daily haiku for a couple of years, and figured that the accountability of mailing the haiku to an actual person would drive me to improve.

“It was also a confluence of two ideas: The Rumpus’s ‘Letters in the Mail,’ which reminded me how sweet it is to receive an actual letter in the mail; and live-writing poets, like Pam Benjamin, who composed poems on demand in public spaces. Pam asserted that a poem written on physical paper constitutes a unique, and therefore worthy of love, artifact.

“For the first month, I just scanned the cards for my own record. Until, duh, I got the idea to pose and photograph them in the wild before mailing them out.

‘This project was the most fun thing I've done, writing wise, and I've done a lot of fun things with a lot of cool writers!’

The project lives in haikuandy.com if you want more info.

If you want to read the haikus in succession, check out this video:

Because create

Another thing I decided to do in each newsletter: provide a weekly creative prompt.

Collecting junk naturally leads to playfulness because of the way randomness and the accidental is part of the process. Go on a random search for text you might create a story with, or text that might stand alone as a story. Look at your junk mail, the letter you receive with a new credit card offer. Look through the emails in your spam folder. Go to the library and read through old newspapers or diaries.

I just took a foray into my Spam folder, and here are three things I found:

1) An email that began with the phrase, “Firstly let me apologise to you …” What a wonderful phrase to start a story with or use to characterize a character.

2) An email from “Mr. Info”: a character named “Mr. Info” could take so many different forms: a know-it-all who always spouts the wrong information or an ominous figure in a sci-fi thriller.

3) A subject line that reads, “Japanese Plant Mix Forces Fat Cells To Melt.” In fact, this 3,000-year-old fat-dissolving tonic burns one pound of fat per day. This tidbit could spark stories from the absurd to the tragic.

See how you can give the “junk” you find a new and different life through the simple frame of a story, a new context. The junkyard of stories is a playground of possibilities.

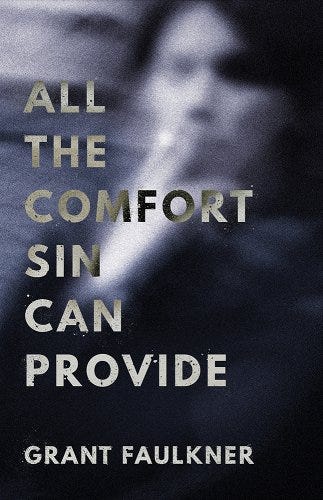

All the Comfort Sin Can Provide

If you like this newsletter, please consider checking out my recently released collection of short stories, All the Comfort Sin Can Provide.

Lidia Yuknavitch said:

“Somewhere between sinister and gleeful the characters in Grant Faulkner’s story collection All the Comfort Sin Can Provide blow open pleasure—guilty pleasure, unapologetic pleasure, accidental pleasure, repressed pleasure.”

Grant Faulkner is executive director of National Novel Writing Month and the co-founder of 100 Word Story. He’s the author of Pep Talks for Writers: 52 Insights and Actions to Boost Your Creative Mojo and the co-host of the podcast Write-minded. His essays on creative writing have appeared in The New York Times, Poets & Writers, Lit Hub, Writer’s Digest, and The Writer.

For more, go to grantfaulkner.com, or follow him on Twitter at @grantfaulkner.

Thanks so much for including my haiku. I wish we’d known each other back then, I’d have loved to include you.