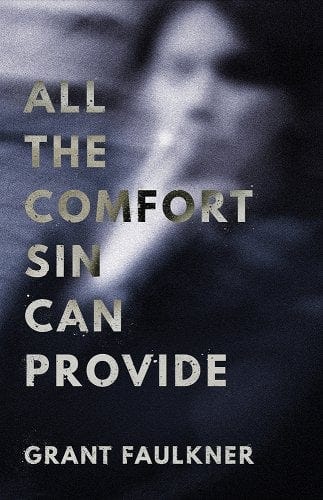

I just finished my final, final, final revision of my novel, The Letters (pictured above), so I’m pausing to reflect on the somewhat odd labyrinthian path it took into being (and just so you know, most novels, like most people, take an odd labyrinthian path into being).

Let’s start with the “final, final, final”—which should have more “finals” attached to it. I have separate folders on my computer titled “2017 Revision,” “2018 Revision,” etc., all the way up to 2024—so eight folders in total, but I don’t know how many revisions I truly did.

I do remember thinking that the novel was done in 2017, though, and I sent it to my agent, and, well …. it seems it wasn’t done.

So my wisdom is that a final revision is rarely a final revision. In fact, I promise to pinch myself in the future to remind myself that the first final revision is likely an act of overexcited hubris—that a final revision is actually just one step in a long writing process, followed by the ever-crucial “final, final revision.”

The Letters was conceived in a moment of reckless passion.

But let’s go back from the novel’s graduation to its beginnings. The Letters was conceived in a moment of reckless passion (as all of my novels have been). Yes, as in the backseat of a car at the drive-in.

In my collection of 100-word stories, Fissures, I’d written 20 or so tiny stories about a love affair between two characters, Gerard and Celeste. People responded favorably to those stories, so I decided to stitch them together into a longer story, “Gerard and Celeste,” which is in my collection of stories, All the Comfort Sin Can Provide.

But then I got a kooky idea. I’d just read Roland Barthes’ A Lover’s Discourse, which is my favorite book about romantic love—it brilliantly evokes and analyzes the many sides of love through Barthe’s keen literary analysis, yet it’s an emotional book, a lyrical book, and I view it as a poem to love. In fact, Barthes wrote it as a result of letters he’d written to a man he was obsessed by.

I wondered, “What if I take the thoughts in A Lover’s Discourse and return them to letter form by writing a novel in the letters Gerard writes to Celeste?”

An epistolary novel. Perfect for me because I’ve always felt like my writing was at its best in letters. And I missed writing letters (oh, the pre-internet letter-writing era was such a lovely, sumptuous era of writing).

An easy novel to write

And then … here’s where I made a crucial miscalculation … I thought it would be easier to write a novel through letters than through a conventional narration. I thought I could frolic in a story told through lyrical fragments—that the novel, in fact, would be less dependent on a plot because it would be more of a poem.

What I didn’t anticipate: the opposite was true. Telling a story through letters made it more difficult to write scenes with dramatic pressure—especially because the letters weren’t a back-and-forth between the characters, but from one character to another, so they were more like a diary. A confession.

A friend recommended I put a narrative frame around the letters (which I reluctantly did, but it made the novel better, so it pays to listen to feedback). An agent told me she wasn’t drawn to the voice of the letters (it’s true, the voice becomes so much more important in a novel like this—the voice has to play the role of the plot in a way, as a driver of the story).

What I realized: I couldn’t indulge in the lyrical meanderings I’d initially hoped for—I needed to find ways to lace layers of dramatic tensions throughout the novel, but without the normal tools of conventional narration.

Hence the final, final, final, final, final, final, final, final revisions. It was the biggest challenge I’d ever faced as a writer. And, without arrogance, I think this last draft nails it (I rarely say such things, but … all of those “finals” provide a smidgen of confidence).

My journey with this novel likely isn’t done. In fact, I hope it isn’t, because I hope it finds an editor who wants to publish it, and I hope that editor proposes edits and opens new ideas for the story.

But the journey so far has posed several interesting writing questions:

What actually goes into a revision?

What role does plot have in an unconventional story? (Or does plot even matter?).

How do you know when a novel is done?

What role does rejection play in a novel’s development?

I thought I’d answer these questions in the next few newsletters if you’re game to read about the inner machinations of my writing process. The toils and tribulations. The unexpected rewards.

Because Gerard and Celeste

Here’s one story from the initial 100-word stories in Fissures.

Souvenir

When Celeste thought of Gerard late at night, she emailed him tracks of yearning sexy songs. “Sorry to rape your ears,” she wrote. She enjoyed thinking of her songs popping up on his iPod years later as he sat in his living room with his wife. “I love this song,” his wife would say. “Where did you get it?” She imagined Gerard’s eyes blinking, then gazing off into a memory of her, an ornery whiff of the past. True lovers are expert in constructing penitentiaries. She’d hammer a nail into his hands for eternity, even as she listened to static.

Because a quote

“Half my life is an act of revision.”

~ John Irving

They really do. I love and hate that:-)

Great post. It really captures the way novels, well, insist on themselves. Good luck with it!