Since it’s the end of the year, I’ve been thinking about endings— specifically, how challenging it is to write a good ending.

Hemingway famously wrote 39 different endings to A Farewell to Arms, and nearly every writer I know has wrangled with a recalcitrant ending in a similar manner (you can now read all of Hemingway’s alternate endings).

An ending is a tiny landmass in the overall geography of a story, but it can have the largest and most vital presence. So often we remember the ending of a story more than we remember any other part of it.

I always say you’ve got to nail the ending like a gymnast, especially in shorter pieces. If you waver, tip, or fall, you’ll ruin everything you’ve previously achieved. But there are so many different ways to define how to nail the ending.

“The end of THE END is the best place to begin THE END, because if you read THE END from the beginning of the beginning of THE END to the end of the end of THE END, you will arrive at the end,” wrote Lemony Snicket in The End.

Spoken like a novelist. A novelist who perhaps doesn’t want to end the end, or really can’t locate the end, because the end can be hard to locate, as Italo Calvino describes a very fatigued ending in The Baron in the Trees:

“That mesh of leaves and twigs of fork and froth, minute and endless, with the sky glimpsed only in sudden specks and splinters, perhaps it was only there so that my brother could pass through it with his tomtit’s thread, was embroidered on nothing, like this thread of ink which I have let run on for page after page, swarming with cancellations, corrections, doodles, blots and gaps, bursting at times into clear big berries, coagulating at others into piles of tiny starry seeds, then twisting away, forking off, surrounding buds of phrases with frameworks of leaves and clouds, then interweaving again, and so running on and on and on until it splutters and bursts into a last senseless cluster of words, ideas, dreams, and so ends.”

An ending sometimes does seem to be an act of “cowardice or fatigue, an expedient disguised as an aesthetic choice or, worse, a moral commentary on the finitude of life,” as Michael Chabon writes in The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay.

Or, as Frank Herbert said, “It’s just the place where you stop the story.”

Finding the poetry in the ending

The worst ending, at least for me, is one that forces a twist upon the story—a supposedly clever paradox, an odd coincidence that fails to illuminate or truly reveal anything.

Is simple surprise the goal of an ending? If that’s the case, then the story whose purpose is the twist at the end functions like someone flicking off your cap as you walk down the hallway.

I suppose such endings are spawned by the idea that an ending must hold a dramatic reversal, but reversals hold their own creative hazards. I see too many writers ruin their stories with such overreaching when a subtle reversal, a nuanced recognition is preferable. Charles Baxter advises writers to pursue a discovery at the end that is simply an “emergent precious thing,” which keeps the focus on finding something new and intriguing, giving the reader a final gift.

Perhaps poets know more about endings. “The love of form is a love of endings,” wrote the poet Louise Glück. I think this definitely applies to the endings of flash fiction pieces. Since writing a short-short places the writer in keen attunement with form—rather than the rambling spirals that a novel might have—the ending becomes more palpable, more pronounced, more of a key ingredient.

Poetry also is tuned to an ending that relies on association. One reason to study haiku is because of the associative leap that tends to happen between the second and third line. That leap travels through the ending, an unfinished breath.

The idea of an associative leap is why I chose the photo of the lights in the darkness above—because an ending is often a blurry light leading you forward through the darkness. An ending doesn’t have to be sharp and certain, in other words, and is best when it’s not.

David Shields thinks an ending should provide “retrospective redefinition,” like the couplet at the end of a sonnet that turns the poem in a new direction—it should make the reader view the story they have just read in a new light that requires them to think of it differently.

I was once told that the best way to end a story is to end it two paragraphs earlier, so I always look at my endings and see how they read if a substantial chunk of them is taken away. It’s interesting how in the attempt to write a good ending, we keep going further, writing more. I find it’s as true as any writing advice I’ve ever received.

I like the writer Jayne Anne Phillips’ definition for the ending of a short-short. She said that the last lines of a short-short “should create a silence, a white space in which the reader breathes. The story enters that breath, and continues.”

What better way to end could there be?

Photo credit: "End of 2012 (23 of 55)" by ni7enichi is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Because a Haiku

I’ve been including one of my haikus each week, but today I’m going to feature Jack Kerouac, who lovingly called haikus “pops,” which is the perfect label for his style of haiku.

Here’s what Kerouac had to say about the haiku form:

"The American Haiku is not exactly the Japanese Haiku. The Japanese Haiku is strictly disciplined to seventeen syllables but since the language structure is different I don’t think American Haikus (short three-line poems intended to be completely packed with Void of Whole) should worry about syllables because American speech is something again…bursting to pop…. I propose that the ‘Western Haiku’ simply say a lot in three short lines in any Western language. Above all, a Haiku must be very simple and free of all poetic trickery and make a little picture and yet be as airy and graceful as a Vivaldi Pastorella."

Here’s one of his:

In my medicine cabinet the winter fly has died of old age

Because Photos Take Us to New Places

I took this photo at a summer rodeo in Carbondale, Colorado, when I had the good fortune to spend a month at a nearby writing residency. There’s nothing like a rodeo to create a swirl of stories—and so much to photograph.

Use this photo as a prompt, as a random catalyst, as an igniter for any writing project you’re working on.

Or … simply write a story about this photo in less than 250 words and share it.

Because Brilliance

Leesa Cross-Smith is a master of the story as poem. Or perhaps it’s the poem as story. I can read her stories, especially her sensual and lyrical short shorts, and not truly know if I’m reading a poem or a story.

I love her intimate, honest, impressionistic style, the rich and rhythmic way her sentences move on the page. She’s an author I read because I don’t know what she’ll do with words.

So check out So We Can Glow. I bet you’ll lose yourself.

Because Lists

The worst thing about making a book list is … that you’ll inevitably leave a book out. Even a favorite book. Or (as in this case) the website doesn’t carry some of the books you love.

But lists are fun, and they guide us to new things, so it’s in this spirit I offer this list of Favorite Flash Fiction Books.

Buy a book and support an author—but mainly just enjoy the stories!

Because bell hooks Is Wonderful and I Will Miss Her

“Love is an action, never simply a feeling.”

~ bell hooks

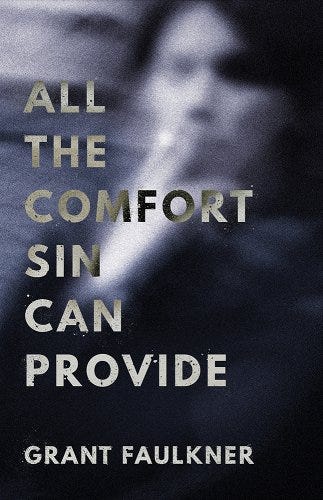

All the Comfort Sin Can Provide

If you like this newsletter, please consider checking out my recently released collection of short stories, All the Comfort Sin Can Provide.

Lidia Yuknavitch said, “Somewhere between sinister and gleeful the characters in Grant Faulkner’s story collection All the Comfort Sin Can Provide blow open pleasure—guilty pleasure, unapologetic pleasure, accidental pleasure, repressed pleasure.”