It’s the season of masks. The season of becoming someone or something else—to find yourself—to flee yourself. Or to find yourself and flee yourself at the same time.

Masks can give you power. Masks can also take away your power.

The use of masks dates back to the beginning of human history. A fundamental part of being human is to imagine yourself as something else. Some think that the first masks were worn so that the wearer could have the authority of the gods. We all want to be gods of some sort.

In the Greek bacchanalia, masks allowed people to go beyond the regular norms of behavior, to cavort, to push the boundaries of excess. Conversely, Celts wore masks on Halloween to protect themselves from bad spirits that roamed the earth on All Hallows Eve.

There are also masks that aren’t physically worn. There’s the mask of name-dropping when you feel insecure. There’s the mask of pretending things are fine to make sure another is happy. It might be a good exercise to list the different sorts of masks you wear, and for what reason, just to see how different masks serve you.

It’s often easier to keep a mask on instead of letting the world see you for your true self. As the poet E. E. Cummings wrote, “The greatest battle we face as human beings is the battle to protect our true selves from the self the world wants us to become.”

Hence the many masks writers have worn as a conduit to their truths. Sometimes a name—your name—can get in the way of your creativity. Sometimes your very sense of yourself, your identity, your history, and your expectations for who you are narrow your story instead of widening it.

To write is to create a persona

Wouldn’t it be nice to write with a degree of invisibility, where we don’t feel ourselves scrutinized or victim to the snarls of potential critics? Wouldn’t it be nice to write as an entirely different person—one who is brazen and dashing, and maybe a bit reckless? Just someone else—someone who opens a path to our story, who enlivens it with brio and possesses an angle that we somehow don’t have access to?

“Give a man a mask and he'll tell you the truth.”

A new name can provide a fantastic sense of liberation. A shy Victorian mathematician at Oxford named Charles Lutwidge Dodgson only felt free to let his imagination run wild through the protective guise of Lewis Carroll. Sci-fi writer Alice Sheldon (aka James Tiptree Jr.) decided to hide her gender within the male-dominated field of science fiction to have her work considered for publication. Likewise, Amantine-Lucile-Aurore Dupin wrote as George Sand, and Mary Ann Evans went by George Eliot.

My friend Laura Albert, who channeled a character named JT LeRoy to tell her story, likes to quote Oscar Wilde: “Give a man a mask and he'll tell you the truth.”

Laura has said that there is no way of writing anything without the assumption of some kind of persona. “The writing voice is a persona,” she says. But for her, LeRoy was not just a voice; LeRoy was a shield that enabled her to tell her truth. She’s described LeRoy as the gloves that allowed her to “manipulate materials too dangerous to be touched directly.”

Perhaps that’s why Patricia Highsmith published her novel about lesbian love, The Price of Salt (later republished under the title Carol), in 1952, under the nom de plume of Claire Morgan—so she could touch dangerous materials.

A pen name allows you to take risks that are too foreboding or forbidding under your real name. A pen name allows you to inhabit a persona that’s more exotic or exciting than your own. A pen name allows you to change the perception of yourself to others. It’s like a force field you construct around yourself; it will protect you from recriminations, unwanted critiques, the judging eyes of others.

More importantly, perhaps, a nom de plume allows you to change your own self-perception. We’re all boxed into some sort of corner of identity—a box that we sometimes construct ourselves. So a new name = a new self = a new writer.

The word person comes from the Latin persōna (“mask used by actor; role, part, character”), so one might say we are intrinsically the masks we create, the masks we wear. A mask is part of the definition of being itself.

The key questions? Does the mask you wear help you achieve authenticity or is it inauthentic? Does it help you create or are you hiding behind a mask?

Only wear masks that give you greater powers.

Because a quote or three

“Love takes off masks that we fear we cannot live without and know we cannot live within.”

—James A. Baldwin

“When you wear the mask, the mask becomes you.”

—Qiu Xiaolong

“If you want to say something and have people listen, then you have to wear a mask. If you want to be honest then you have to live a lie.”

—Banksy

Because it’s time to get ready for NaNoWriMo

Speaking of time and stories, check out NaNoWriMo’s NaNo Prep resources—and sign up to write! Just go to the National Novel Writing Month website—it’s free!

You’ve got nothing to lose and a novel to gain.

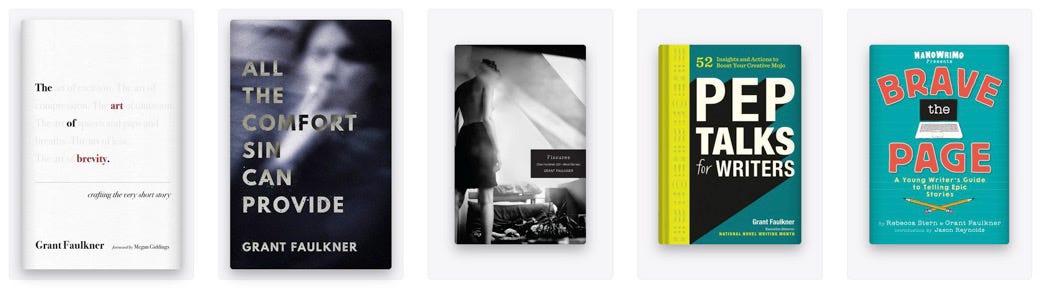

Because I’d love you to read one of my books

I write this newsletter for many reasons, but mainly just for the joy of being read and having conversations with readers. This newsletter is free, and I want it to always be free, so the best way to support my work is to buy my books or hire me to speak.

Great post, thank you! I’ve always wondered about how liberating it would be to use a pseudonym, especially for nonfiction writers. But don’t we all have a signature style that people can actually smoke us out?!?!? This post reminded me of a phenomenal book I read in translation from the Japanese. MASKS by Fumiko Enchi. My post on the book is at https://open.substack.com/pub/kalpanamohan/p/the-masks-we-wear?r=4uv5u&utm_medium=ios&utm_campaign=post