Trust and Distrust and Trusting

Heightened states of vulnerability open up the world in interesting ways. Necessary ways.

I just went into the hospital for my second heart procedure of the last few months—a cardioversion, which is where they put you under and then shock your heart to try to get it to return to its normal rhythm.

I had ablation surgery last August for my atrial fibrillation, and it worked, for a while, and then it didn’t work. I joke that my heart is stubborn: it wants to play a piano solo with all of the disjointed syncopations of a Thelonius Monk solo. So I literally do beat to the beat of a different drummer.

Hence the cardioversion. A little “heart edit” as my friend June calls it, which is a good way to put it (because my big, sloppy mess of a life needs a good cleaning up, you might say).

Although a cardioversion is a medical procedure, I started to think of the edits as a creative act. In short, the surgeon follows the rules of grammar (science), but he has to listen, monitor, and interpret what the body is doing—the story the body is telling about itself—and act accordingly.

On my end, I open my body up, quite literally. My hospital gown is designed so they have full access. They’re both inside my body and outside it. I open up not only my body, but my whole life, and to people I don’t even know.

Here is where I pause: I don’t know if they might have gone on a bender or had a bad night’s sleep. I don’t know if they’re torn apart by a bad marriage or if they’re worried about wayward children. I don’t know if they might have their own health concerns or if their thoughts are full of the anxiety of unpaid bills. Or all of the above.

Yet I trust them. I have to trust them. Because I need them to keep me alive.

The trust at the center of creation

Trust is the foundation of any relationship, any love, but trust is also dangerous. Trust is a gamble. And a violation of trust can be traumatic. In fact, to have trust betrayed might be the definition of trauma—whether it’s love that turns into not-love (or worse), the affliction of an injustice you can’t defend yourself against, or the world just serving up its random tragedies.

Trust shapes how we love and how we learn, why we succeed and why we falter—but even more importantly, trust isn’t only about trusting others. Truest defines our relationship with ourselves. The nature of our self regard is caught up in the tangle of emotions with which we hold it.

We bring a similar trust to our art. To create anything—a story, a painting, a conversation—is to place our faith in invisible forces: in our own competence, in the possibility that our work matters, in the willingness of the world to receive what we offer.

Without trust, the blank page remains blank. Without trust, we never speak the difficult truth; we never even begin.

Yet even though ttrust is the foundation of every creative act, I think we rarely acknowledge it. When a writer sits down to write, they trust that their memory is worth excavating, that their particular way of seeing has value, that language can illuminate experience—and that the hours spent alone shaping sentences no one has asked for will somehow find their way to readers who need them.

By opening up, we risk being unliked. That is not a small risk, yet it is the risk necessary to form the truest of connections. We have to trust that the world contains people who will understand, or at least try to. We have to trust that our collaborators—whether they are co-writers, editors, friends who read early drafts, or the anonymous readers we imagine—will meet us with some measure of generosity.

Without this trust, collaboration becomes impossible. How could we share half-formed ideas if we believed they would only be ridiculed? How could we accept feedback if we didn’t trust that critique comes from a desire to help us improve rather than diminish us?

Trusting too much?

My grandmother once told me that I trusted others too much, and in many ways she was right, I tend to leap into trusting others. I’ve been let down many times as a result, but mainly my trust has lifted me up, opened up new experiences, opened my heart.

We have to show our work to others knowing we might be misunderstood. We have to collaborate knowing that people will disappoint us, that our visions will clash, that the thing we build together might not look like what we imagined alone.

Yet we have to write the book, start the company. We have to say “I love you” not because we have guarantees, but because the alternative—a life lived in protective isolation—is worse than the risk of heartbreak.

This trust isn’t naïve. It’s not a refusal to see darkness or difficulty. It’s something more essential: a decision to believe that meaning is possible, that connection is worth pursuing, that our efforts aren’t entirely futile.

The artist who has been rejected a hundred times and submits their work for the hundred-and-first time is demonstrating a profound trust—not that this time will be different, necessarily, but that the act of trying still matters.

Consider what it takes just to move through an ordinary day. We trust that the sun will rise, that gravity will hold, that the social contract will mostly function. We trust that when we speak, we’ll be mostly understood. We trust that our bodies will carry us where we need to go, even knowing they will eventually fail.

We trust that the people we love will mostly return that love, even though we know love can evaporate without warning. Every action we take is underwritten by thousands of small trusts we never consciously acknowledge.

And when times are hard—when we’re grieving, when we’ve failed, when the world feels hostile—trust becomes the thread that pulls us forward. We trust that this pain won’t last forever, even when it feels permanent. We trust that there are people who would help us if we asked, even when asking feels impossible.

This trust in our own resilience, in the possibility of change, is what allows us to endure. Without trust, we would be paralyzed. Every decision would require absolute certainty, and absolute certainty doesn’t exist.

Writing as an act of faith

The creative act, then, is an act of faith. Not religious faith necessarily, but existential faith: the belief that our efforts ripple outward in ways we can’t predict or control, that our work joins a larger conversation, that we are part of something that transcends our individual limitations.

Perhaps what we call creativity is really the practice of trust made visible. Every sentence written is an act of faith that language matters. Every difficult conversation is a bet that honesty might lead somewhere better than silence. Every morning we get out of bed and try again is evidence that we still trust that our lives have purpose and possibility.

And maybe that’s the deepest truth: we create not because we’re certain our work will endure, but because the act of creating reminds us that we’re alive, that we’re connected, that we matter to each other.

The world doesn’t promise to catch us. But we leap anyway. That leap—that gorgeous, terrifying, necessary leap—is trust. And it’s the only way anything has ever been made.

So I give thanks for trust. I am especially thankful to all of the medical professionals who touched me in so many ways this past week: physically, emotionally, and spiritually. I didn’t get to tell many of them thank-you. They were gone when I woke up. I didn’t even know many of their names.

Yet I trusted them.

Please help me publish this newsletter?

Because a quote

“When we were children, we used to think that when we were grown-up we would no longer be vulnerable. But to grow up is to accept vulnerability... To be alive is to be vulnerable.”

—Madeleine L’Engle

Book touring!

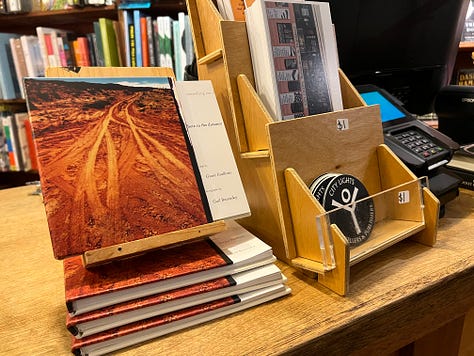

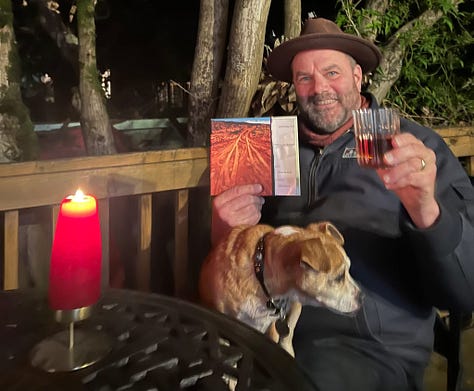

I hope you can make it to one of our bookstore events for the book of photos and stories Gail Butensky and I published, something out there in the distance.

Andre Dubus III on Exposure and Harm in Memoir Writing

It was great talking to Andre Dubus III on the Memoir Nation podcast because he took us on a ride through some of memoir’s more confounding territory—what’s yours to tell; considerations of harm; writing about violence; and getting to truth on the page.

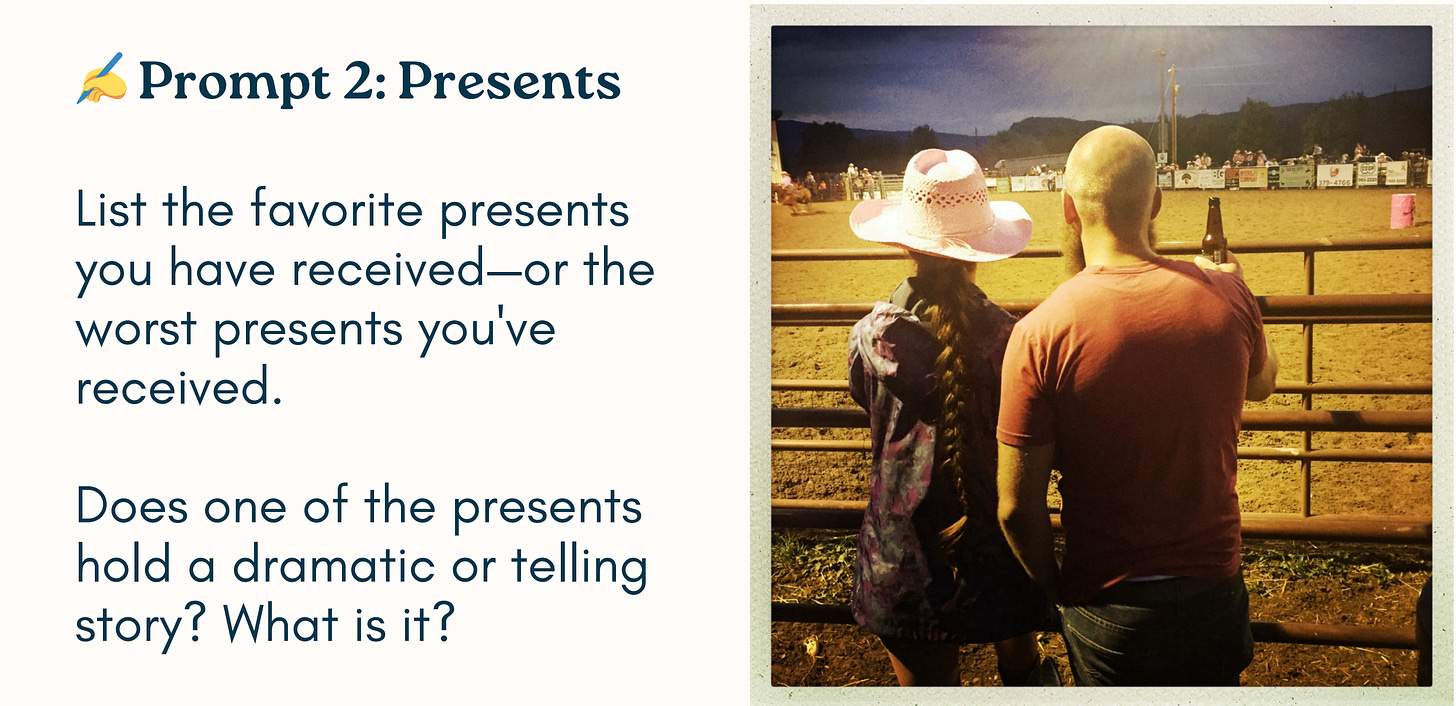

Because a prompt

Here’s a photo + writing prompt I recently used recently for a class with the London Writers Salon. Some context: I took this photo at a rodeo in Colorado.

You can write about the good and/or bad presents you’ve received or given over the years. Or write about a present one of the two people in the photo is going to give another. Presents can spark drama.

I hope you continue on your path to recovery with a healthy heart, Grant. We see how graciously you share your heart with us every time you write your meaningful pieces.

How serendipitous that I read this. I always find so much inspiration in your writing. The title drew me into this one and I giggled with a sense of familiarity because for the past few weeks, I’ve been mulling over writing an article about trust, and how we can’t avoid it, we have no choice in nearly every aspect of our lives, without realizing it, some much bigger than others, as you’ve pointed out in trusting medical professionals.

I think they’re saints, and I can’t imagine doing what they do, day in and day out.

Talk about vulnerability and trust, to literally open your body up to strangers, and not even know all their names. The vivid detail of the gown you wore, that did it for me, seeing your chest open, imaging you on the table like that, and now here you are. I want to cover you up and place hands on your stitches and bless you and hope everything heals so that you can keep on writing and being of service to us writers for many, many years to come. Thank you for sharing this journey with us.