“Coincidence is God’s way of staying anonymous.”

If you listen to any interviews with the renowned producer David Milch, you’ll likely hear him say this. I heard it first, however, from Laura Albert (aka JT LeRoy), who I met quite by coincidence, and then wrote a screenplay with, also by coincidence.

She was a writer on Milch’s TV show Deadwood, so she used to send me links to his writerly advice, and I found it a wonderful way to learn—to follow the coincidences that landed in my Inbox.

One can view coincidence within the prism of mathematical probability, and it certainly has a place in such: in some ways our lives are just a series of random collisions, bumps, and brushes that shape our lives. But even as a bona fide atheist (with a a bit of a mystical bent), I appreciate Milch’s view of coincidence as an entrée into understanding our lives in a more sacred way.

To view coincidences on such holy ground is to elevate the mundanity of our daily acts, to see life as a grand quilt, all of us woven together—“together” being the key word. When coincidence happens, we must pause and reflect on the chain of events that is wrapped around the coincidence. We must interpret actions, size up who we are, what we want, what we will allow to happen.

This isn’t an essay about new age matters or any woo-woo stuff, though. It’s an essay about being a writer and the role coincidence plays in our creativity. Being a writer is the most accurate metaphor for being a human being that I know of. We are our stories. We are revisions of our stories. We are stories in the making. And all of that is made up of a series of coincidences that demand interpretation (and indulgence).

Please contribute your spare change to help me publish this newsletter.

Milch, who now has Alzheimers and lives in an assisted-living facility, was compelling as a raconteur who had the necessary distance to be charmed, appalled, and endlessly intrigued by his life. He constantly called upon the cosmic consciousness when he spoke of writing, something not only beyond the self, but a truth that could only be reached by abdicating oneself.

In this way, much of his perspective seems spawned by Buddhism, although he was more likely to quote the Bible.

The illusion of being alone

When Nietzsche declared that God was dead well over 100 years ago, it began an age of existential isolation, perhaps especially for artists, who burrowed into the fragmentation and separateness of modernism. Milch disagreed with creation based in isolation, however.

“The modern situation is predicated upon the illusion of the self’s isolation—that business of I’m alone, you’re alone, but we can bullshit each other when we’re fucking or whatever else, but the truth is we are alone. Right? Well, I believe that that is fundamentally an illusion,” he said in a 2005 profile in the New Yorker.

Such a belief puts an interesting frame on Deadwood, a show that places a crew of mostly heartless exiles together in a practically lawless place, all of them tied in one way or another to gold, hardly a substance that brings people together in loving connection. Milch said the show was “about individuals improvising their way to some sort of primitive structure.” A structure is a form of togetherness by definition.

That is the definition of having a muse: to try to touch another.

I’m interested in how Milch comes out of the “primitive structure” of self to develop stories layered through the lenses of so many characters. He hearkens back to William James, who said in The Variety of Religious Experiences that “every vision that ever came to anyone is prefaced by a sense of the dissolution of the self.” Milch says, “it’s the fragmentation of ego that allows what he called the oceanic sense to flow in.”

Going out in spirit

Too often, we write and act with our egos, as if our egos are a prized fastball. Milch isn’t always beyond such a state either, but he says that “what writing should be is a going out in spirit.”

Every writer ponders subtext and characterization, tone and point of view, dialogue and plot—but what about “going out in spirit”?

I think of Hemingway’s dictum to “write one true sentence.” Such a simple rule on the surface, but one that must be pondered like a zen koan. I’ve found as a writer that it’s easier to write untrue sentences, just as it’s easier to live an untrue life—imitating others rather than genuinely creating—no matter the toll on the soul. One must be highly attuned to the truth and quite brave to represent it, delve into it, and live it.

In the case of Deadwood, Milch did the research, then suppressed his self and let the visions come. “Visions come to prepared spirits,” he said.

Milch wrote his visions in a roomful of a various people he’d brought in for inspiration (a motley crew of rodeo cowboys and yahoos in the case of Deadwood) and he channelled characters, dictating the story as he lay on the floor. The act of writing was literally a “going out in spirit” for him.

“All I want to understand is the mind of God,” said Milch, quoting Einstein. “Now, I don’t want to understand it; I want to testify to it. I believe that we are all literally part of the mind of God and that our sense of ourselves as separate is an illusion. And therefore when we communicate with each other as a function of and exchange of energy we understand not because of the inherent content of the words but because of how that energy flows.”

My best writing happens with such a sensibility—when I feel connected with others, when I am writing to and for others, with a sense of touching them, whether real or imagined, it doesn’t matter. That is the definition of having a muse: to try to touch another. Creation is fundamentally an erotic act.

And the erotic is about the relinquishment of self, contrary to its popular portrayal of it being a self-indulgent pleasure. Like Milch, I believe that the self clouds or blinds vision, so becoming a good writer and becoming enlightened essentially go hand-in-hand. It’s the ultimate feeling of opening up, giving oneself away, an act of generosity rather than the stinginess of ego.

That’s what is key in writing to a muse—generosity and the desire for connection guide one’s words. The writing isn’t about the self so much as it is about a mystical, spiritual connection, which has to be honored and revered as much as any God, for it is, in the end, a pathway to the sacred.

Intimacy is not just a state to reside in, but a guide.

As an exercise, start writing down the coincidences that occur in your life, and then read the stories the coincidences tell. See if they open up a pathway to your muse. Follow that pathway with the lightest of touches.

Because a quote

“There is, for me, no difference between writing a good poem and moving into sunlight against the body of a woman I love.”

—Audre Lorde

I’m available for book coaching and editing!

I love working with writers, and I have some space on my Writing Consult calendar if you’re looking for help.

I help people develop books and projects from scratch and sometimes do larger edits on finished manuscripts.

Lately, I've worked on a few novels as well as some short story projects. I’ve also worked on helping people figure out what kind of writer they are or want to be, and which projects can help get them there.

Contact me to find out more about my one-on-one work with writers.

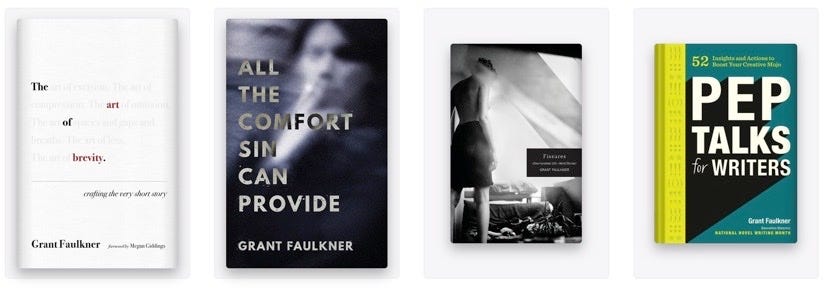

Because buy my books!

Because a photo

I’ve been in Los Angeles this week. This view seemed very LA to me.

So much in your essay resonates with me, Grant, including the idea of “viewing coincidences as an entrée into understanding our lives in a more sacred way.” Borrowing from Jung, I call them synchronicities. And I love your reference to David Milch’s claim that writing “should be a going out in spirit.” Thanks for this.

"I believe that the self clouds or blinds vision, so becoming a good writer and becoming enlightened essentially go hand-in-hand." Yes!