Walking with the dead

And thinking about the living

I grew up just down the street from a cemetery, so the dead were always near me as a child. I sometimes went to bed worried that a ghost would escape the cemetery’s gates and traipse down the street to our house (as if ghosts would know such boundaries).

But the cemetery was many things to me more than just a cemetery: it was a playground, a hideout, a refuge, a sanctuary. I fed the ducks in its pond, caught frogs, and ice skated there as a boy. I ditched class and hid out there as a teen.

I often think about the conversations I had with my friends—huddled in Kevin’s Maverick listening to Joy Division or X or Blondie and talking about the existence of God or Nietzsche or just our romantic dreams (although we didn’t know they were “romantic dreams”; they were just life to us). Those conversations were a much better education than we could have gotten in the classroom.

Sometimes, when I’ve met people who grew up in cities, they assume that I had a boring childhood (more than once when I’ve told someone I grew up in Iowa, they’ve said, “Oh, I’m sorry.”). I always want to tell them, no, it was exciting in so many ways. And one of those ways was the life the cemetery provided.

Now the cemetery is a place to meander on my trips home. I take many walks there. It’s interesting how walking through the cemetery isn’t like walking down a neighborhood street or amidst buildings in a city. It’s also not like walking in the woods or along a beach. I walk amidst people, somehow. The dead become strange companions.

I imagine a nightly party, where the ghosts emerge from their graves and mill about as if they’re hanging out at the town square. They’re watching me, and I’m watching them.

Strangely enough, I don’t visit my father’s grave, I don’t visit my good friend Lisa’s grave. I don’t want anyone I’ve loved to become a tombstone. I can visit them in so many better, more meaningful ways.

My meanderings offer moments of realization about the limits of our aspirations. No matter the size or splendor of a mausoleum or the grand flourishes of a tombstone, you’re dead, no different than those buried under flat and faded tombstones. Your bones are perhaps better taken care of, but that’s it. We’re all food for the worms.

Some wise person who I’ve now forgotten once said that the definition of a soul is the memories we leave behind. You can’t buy those memories. You can’t order them to appear. They have to be created with a generous and lively spirit if they’re going to mean anything.

If I had time, I’d write a story for each tombstone.

I think growing up near the cemetery nourished a mystical streak in me. As much as I might shape my mind toward logic and empiricism, mystical leanings guide me. It’s just more fun to be mystical. It’s certainly more comforting. And also more exciting—because a ghost just might escape a cemetery’s confines and visit me.

So it was nice to visit my dead friends this past week once again.

Because I like to walk (and think about walking)

“A lone walker is both present and detached, more than an audience but less than a participant. Walking assuages or legitimizes this alienation,” wrote Rebecca Solnit in Wanderlust: A History of Walking.

Yes. This is my preferred state. To be a witness. There but not there. Passing by.

Because a quote about how to be treated

“You’ve got to tell the world how to treat you,” James Baldwin observed in a conversation with Margaret Mead. “If the world tells you how you are going to be treated, you are in trouble.”

Because a haiku

The long day wanes the moon, another moon— is it too late?

Because prompts take our stories to new places

Use this photo as a prompt, as a random catalyst, as an igniter for any writing project you're working on.

Or … write a story about this photo in less than 300 words and share it here.

Because forgiveness

When I think about the grace of forgiveness, I’ll always think of Ashley Fords’ Somebody’s Daughter. Listen to our conversation on Write-minded.

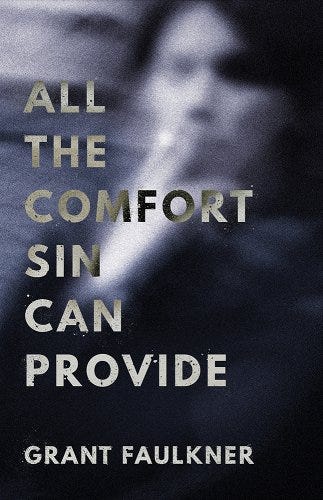

All the Comfort Sin Can Provide

If you like this newsletter, please consider checking out my recently released collection of short stories, All the Comfort Sin Can Provide.

Lidia Yuknavitch said:

“Somewhere between sinister and gleeful the characters in Grant Faulkner’s story collection All the Comfort Sin Can Provide blow open pleasure—guilty pleasure, unapologetic pleasure, accidental pleasure, repressed pleasure.”

Grant Faulkner is executive director of National Novel Writing Month and the co-founder of 100 Word Story. He’s the author of Pep Talks for Writers: 52 Insights and Actions to Boost Your Creative Mojo and the co-host of the podcast Write-minded. His essays on creative writing have appeared in The New York Times, Poets & Writers, Lit Hub, Writer’s Digest, and The Writer.

For more, go to grantfaulkner.com, or follow him on Twitter at @grantfaulkner.

Thank you for writing and inspiring! I too remember going on drives through the cemetery as a kid, sometimes after getting ice cream and getting to feed the swans. I remember taking a new friend there after college who thought it was crazy and told everyone we went there. Did we really marry? And where did all the Mavericks go?

Aaah, Many a trip with Grant and other friends to this place. I've gotten chased by a Swan and lost part of my innocence in this very special location. I too lived even closer to this place. Many relatives reside here and it's a very restful and quiet. I find myself having many conversations with those ghosts - conversations that I so wished I had with them when we could share a laugh or a good cry. I have not ventured far from my family to find others that rest there. Thanks for reminding me though Grant - next time I visit, I will seek their inspiration and spirit.