Dear Readers,

I’ve got a story for you today about an odd path to perseverance that takes a detour through the harrowing and hallowed lands of self-pity.

One of my big writing projects this year has been a book on the subject of rejection (it’s actually been a project several years in the making). The idea for the book is that our reaction to rejection determines who we are, not only as writers but as people.

Do we reach for a tequila bottle when we get rejected? Do we blame others? Do we dig in with determination and try to prove others wrong? Do we quit?

I did a lot of research into the psychology of rejection. I interviewed Marlon James (whose first novel was rejected 78 times) and wrote a sample chapter about him for my book proposal. I lined up other notable authors who had interesting “rejection journeys” to include in the book.

My agent was convinced my proposal was going to get significant interest—in large part because there isn’t another book like this out there. Writers are often told to get a thick skin, but how do you get a thick skin? I wanted to help writers understand their reactions to rejection and form a “rejection mindset.”

Alas, my book on rejection—the book that was supposed to be my pooh-bah of pooh-bahs (and provide much needed income)—was rejected.

It came close several times. Three acquiring editors at three different fantastic publishers wanted to buy it, but when they took it to their editorial boards for final approval, it didn’t quite make the cut. I got a couple of offers from smaller publishers, but the advances weren’t large enough to cover the significant amount of work the book would require.

Each rejection letter came with a joke about how odd it was to have to reject a book about rejection. The joke got old.

What did I do? I did what I always do when I get rejected. I wallow in self-pity. And since I was wallowing in self-pity in a kind of “meta” way this time—thinking about my own “rejection mindset” in the context of all that I’d learned, I came to a conclusion: self-pity gets a bad rap.

Not only does it get a bad rap, but maybe it’s a necessary and vital stage in the creative process.

Wallowing for good

When we hear the phrase “wallowing in self pity,” we might think of a sad sack with a bad case of bed rot lying in a stagnant pool of despair.

Our culture disparages self-pity because it’s an emotional state bereft of any “get up and go” / “pick yourself up by your bootstraps” type of heroic American energy—or so it appears.

The writer John Gardner said, “Self pity is easily the most destructive of the non-pharmaceutical narcotics; it is addictive, gives momentary pleasure and separates the victim from reality.”

Our culture rewards the stoic response. We love characters of quiet determination, not those of noisy despair. To envy, to blame, to be angry—these are weak emotions. If you Google “self-pity,” you’ll get a tidal wave of articles about how toxic it is.

But here’s the rub: wallowing in self-pity is a key part of self-restoration. It’s a vital part of my creative process. I’ll hazard to say that it’s even nourishing.

In wallowing, I’m gathering my forces, unconsciously planning a Plan B, reaching for acceptance of a “new world order” (one without my book). I go to the edge of the cliff of despair and peer over it, but I don’t jump.

Crying releases oxytocin and a bunch of other feel-good chemicals, and my guess is self-pity does the same (hence the wallowing).

Sure, self-loathing can lead down dark pathways to actual despair and depression, but it can also be a necessary phase of one’s response to rejection. My self-loathing or any of my “woe is me” or “the game is rigged” type of blame ends up being energizing for me.

When “fixing things” doesn’t fix things

We live in a culture that is oriented to fixing things. We don’t tend to tolerate the moody, the dark, the despairing.

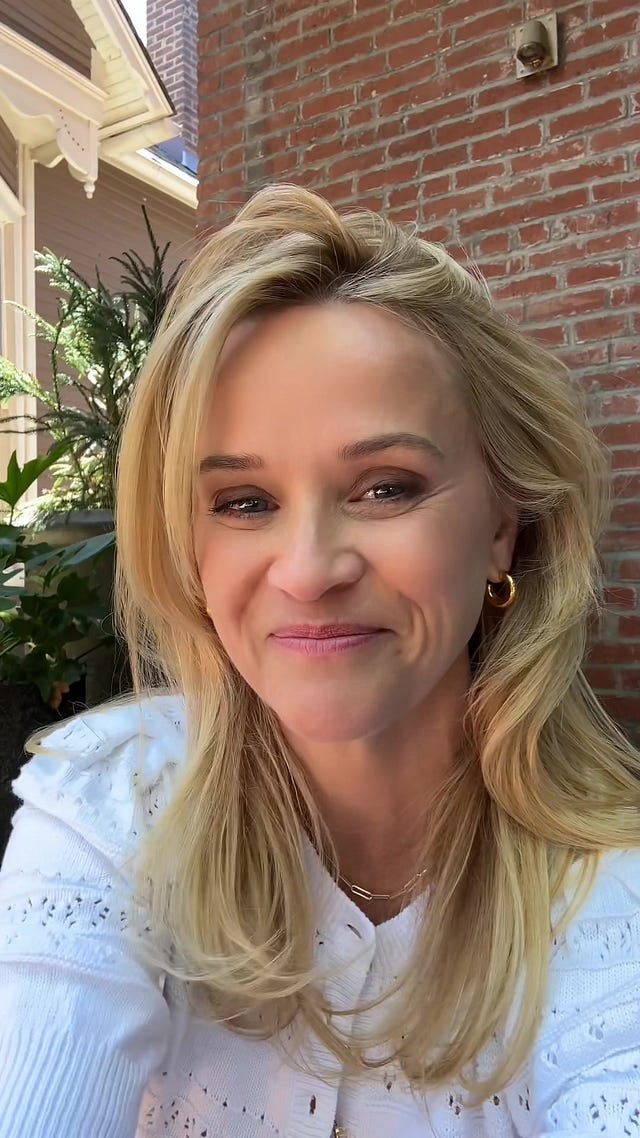

In my Internet meanderings, I recently stumbled on this clip of Reese Witherspoon talking about how she reframes some of the annoying things in her life as opportunities. As in, instead of being annoyed at having to wait for a subway, she “gets to” wait.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

It’s an admirable energy, and I often evangelize similar things myself (for example, I love how John Cage reframed the noise of traffic jams by hearing them as great symphonies).

But sometimes the energy to fix and reframe feels like an unwelcome intrusion on a necessary healing process. Sometimes I like to “get to” nurse my wounds. I want to “get to” wallow because wallowing is a type of mourning, so I don’t want to cut it short.

Self-pity is seen as an unattractive trait because it reveals our egoism: we’re obsessed by our own stubbed toe instead of focusing on the greater pains of the world—or all of the things that aren’t stubbed in our lives.

But we’re human. We’re egotistical creatures. Sometimes a stubbed toe can really hurt, and crying ouch doesn’t prevent us from being able to shift later to more noble endeavors.

We might not be a victim in any larger sense, but we still hurt. We need to cope, and self-pity can offer a type of protection for a crucial part of healing. It’s a retreat. A respite that leads to emotional release.

Saying “Nothing good ever happens to me” might be theatrical, but it’s theater for the soul. As Seamus Heaney writes, in his version of Sophocles’s Philoctetes:

People so deep into Their own self-pity self-pity buoys them up.

So … if you feel like wallowing, please fluff up your pillows, get comfortable, and “enjoy” yourself.

When your determination shows its head again, it will thank you for the vacation from the strains of striving.

7 tactics to maximize misery

Because I’m available for book coaching and editing!

I’ve written extensively about creativity in numerous books and articles, talked with 300 writers on my podcast, Write-minded, led the largest writing event in the world, National Novel Writing Month, and …. well, I’ve just immersed myself in all things writing for a lifetime.

I bring this wisdom and more to my one-on-one work with writers.

Because a quote

“Self-pity in its early stage is as snug as a feather mattress. Only when it hardens does it become uncomfortable.”

—Maya Angelou

Reminds me of a great line delivered with force by Timothy Hutton in the movie "Ordinary People." Interestingly, it occurs toward the end of the movie as a sign of healing—Conrad can deal with a negative emotion without being self-destructive.

Conrad Jarrett : I feel bad about this! I feel really, really bad about this! Just let me feel bad about this!

Dr. Berger : Okay. I feel bad about it, too.

I throw feeling sorry for yourself, or self-pity, into the bucket of other emotions we're not supposed to feel. Rejection is something that happens to you. Your work has been rejected, and your work is all you. But, I remind myself it's okay to feel what I'm feeling. (no, I'm not a therapist!) Self-pity is a most human feeling as you can get, and when writing creatively, I look at it as one of those seeds or even roots from which some good writing can come from. At least for me, anyway.