A few years ago, I made a New Year’s resolution to relinquish my need to be right.

We’ve all been there, right? Whether in a casual conversation or a meeting at work or in a political “discussion” on Twitter, we insist on our version of events, arguing ardently for our opinion.

The need to be right is fundamentally a part of being human because we yearn to be seen and understood, but it can lead to lifelong grudges and even wars (another fundamental part of being human, unfortunately).

I made my resolution because it occurred to me that when you fight for your position in an unyielding way, you usually don’t convince the other person of anything. You’re right all by yourself, and sometimes you’ve made the world a little worse for trying to make another see how right you are.1

It was a fascinating resolution because it was an exercise in humility. Every time I felt the need to do battle, I paused, stepped back, and let it go. I gradually learned that it could be a joy to shrug things off. I didn’t have to deal with all of the emotions that come with digging into a position, and I tended to open up and listen to others more. Instead of arguing, I asked questions. A potential debate became a conversation. It became fun to let others be right.

Enter the Fool

I’m thinking of all of this because I’m thinking of the benefits of being a fool and the Fool’s long literary history. In literature, the archetypal Fool babbles, acts like a child, and doesn’t understand social conventions (or at least pretends not to), so the Fool can speak the truth in ways others can’t. You might say the Fool is the ultimate storyteller: they take risks to tell the tale only they can see.

I essentially became a type of fool by relinquishing my need to be right. I nullified myself in some cases. I became less significant and perhaps less respected.

It’s counterintuitive because we’re taught to be the opposite of the Fool—our society values experts, people who know how to do things right and argue for how to do things right.

Tish Harrison Warren, an Anglican priest who writes a column for The New York Times, recently wrote about the Fool’s role in religion through the lens of one of our most popular pop-culture fools, Ted Lasso.

She discusses the “holy fool”—“a person who feigns insanity, pretends to be silly, or who provokes shock or outrage by his deliberate unruliness.” The irony is that in flouting conventions and inviting in ridicule, the Fool demonstrates allegiance to God, lives closer to love, and teaches the rest of us how to live.

Lasso is an American football coach hired to coach soccer for an English football club—a sport he knows little about—so he’s thrown into the role of the Fool from the start. He takes it all in stride, but he neglects to even learn the rules of soccer or what the game is about. In fact, he angers fans with his lack of concern about winning, saying he cares more about developing his players into good human beings (and he actually means this).

In the opening episode of this season, Lasso is publicly insulted by his former friend and equipment manager, Nathan, who has turned into a rival “wunderkind” coach. The team’s owner, Rebecca, tells Ted to retaliate—our instinctive human urge—but when Ted is asked at a press conference to respond to the insults, he calls Nathan’s comments “hilarious,” praises him as “smart,” and wishes him well.

He then proceeds to essentially do a stand-up bit with himself as the butt of the joke: “I look like Ned Flanders is doing cosplay as Ned Flanders. When I talk it sounds like Dr. Phil hasn’t gone through puberty yet.”

He relinquishes the need to be right and win. He relinquishes the need to be seen as smart and successful. He’s not motivated by ambition, vanity, or fame, and by going against the current, he ends up charming the press, and, with the humility that only a fool can have, he turns a moment of conflict into a moment of levity, even joy.

He also exposes Nathan’s pettiness and “wins” the day, but that’s not his intention. He rejects winning in a world that prizes winning. Warren says:

What appears “normal” and “successful” in the world is revealed by the fool to be hollow, vain, and pointless. What appears foolish, it turns out, is the true path of flourishing. Above all, a holy fool is an icon for radical humility. And this is where Lasso most clearly embodies this persona.

Carl Jung described the Fool as being a “potential future,” meaning that through various attempts and failures, the Fool gains experience, builds character, and eventually develops into the archetype of the Sage or Savior.

The Fool is depicted in tarot cards as looking hopefully skyward. The Fool represents new beginnings, faith in the future.

As a basketball fan, I always appreciated how Phil Jackson embraced Dennis Rodman, who was considered a problem player by many because he flouted sports conventions by adorning his body in tattoos (before tattoos were commonplace), wearing dresses, and dying his hair bright colors. He wasn’t a macho jock, he was something else, something uncategorizable, and that threatened people.

Jackson and Rodman bonded over a necklace Rodman had from the Ponca tribe in Oklahoma, where he grew up. Jackson said that in the Ponca tradition, Rodman would be a heyoka—a backward-walking person. The heyoka was the Fool in that culture, but they were treated with reverence, as a seer, and Jackson decided that having a fool on the team could be a good thing.

Sometimes doing something right means doing it wrong. To be the Fool is to give up power, to revel in playfulness, to live outside the boundaries.

That sounds like a good way to live and create to me.

Because Ted Lasso quotes

"I've never been embarrassed about having streaks in my drawers. You know, it's all part of growing up."

"Taking on a challenge is a lot like riding a horse, isn't it? If you're comfortable while you're doing it, you're probably doing it wrong."

"You know what the happiest animal on Earth is? It's a goldfish. Y'know why? It's got a 10-second memory. Be a goldfish."

Because I like teaching

Writer's Digest is presenting a virtual conference for short story writers on May 19-21. The conference will provide expert insights from seven award-winning and bestselling authors on the finer points of how to write a short story.

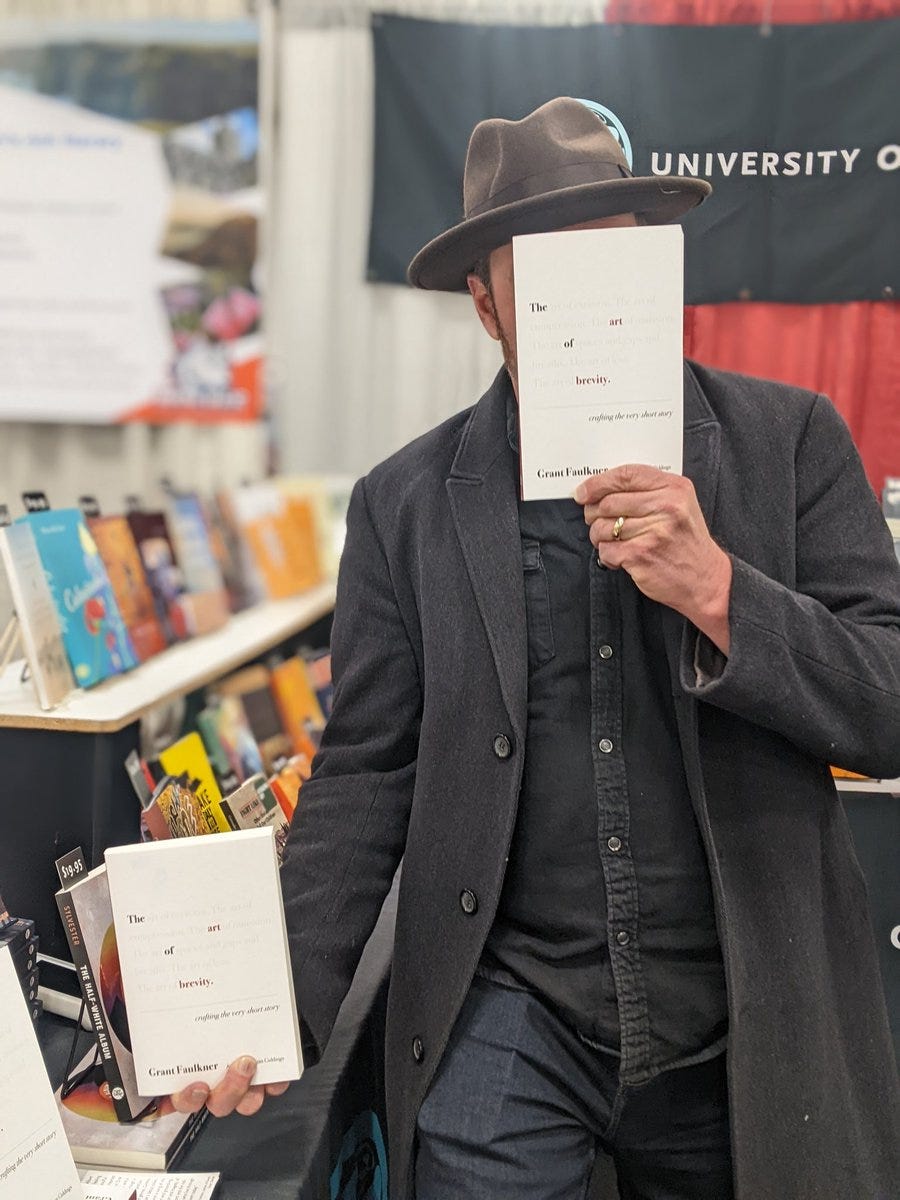

And, hey, I’m one of those authors. I’ll be doing a workshop on my new book The Art of Brevity.

Because The Art of Brevity

Please consider buying my new book, The Art of Brevity. Writers tell me they like it. You might say it’s my way of being a poet in this world. My little stories are my little prayers. I like to drop them into the world.

Because more about me

I am the executive director of National Novel Writing Month, the co-founder of 100 Word Story, and an Executive Producer of the upcoming TV show America’s Next Great Author. I am the author of a bunch of books and the co-host of the podcast Write-minded.

My essays on creative writing have appeared in The New York Times, Poets & Writers, Lit Hub, Writer’s Digest, and The Writer.

For more, go to grantfaulkner.com, or follow me on Twitter or Instagram.

This statement comes with a big caveat, of course. You have to fight for what you think is right when it comes to serious matters like social justice, inequity, and any harmful behavior another person is doing. Also, if you’re one who needs to practice the art of speaking up for yourself, take this with a grain of salt.

Hi Grant, I really liked your post and thoroughly enjoyed the parallels that you used to connect The Fool to Ted Lasso and Dennis Rodman. Your point about sometimes how one must be the fool and not always be right was very well put, well done.

Hi again Grant! I can't believe I missed this one months ago. In any case, I have more for you in connection with my post to you on your other blog. The Rev. Dr. Artress also wrote a book called The Path of the Holy Fool: How the Labyrinth Ignites Our Visionary Powers (https://www.amazon.com/Path-Holy-Fool-Labyrinth-Visionary-ebook/dp/B08KYP4LH1 ). She invokes Emma Jung and Marie-Louise von Franz. Emma Jung was interested in Percival's journey and applied Depth Psychology to that journey. She died before she finished her life's work but von Franz stepped in to finish it. Artress speaks of this book.