I recently spoke to a group of writers who had experienced trauma. Most of them were unable to write, but they still gathered in their writing group regularly, just to be in touch with creativity and keep the door open for the healing balm of a story, the warmth of a connection.

I was invited to speak about writing, but I realized how my usual “stump speech” on creativity wasn’t applicable to this situation. All of my perspectives on things like writer’s block, overcoming creative obstacles, setting a goal and a deadline, and writing with abandon, seemed like they might only not help, but they might do harm.

Trauma is a bull. It is big and burly and overwhelming. It smashes its way through your psyche and shatters all of your assumptions about how the world is meant to be. You’re left alone, stranded, suddenly in an unfamiliar and unwelcoming world.

The bull is unrelenting. Flashbacks, nightmares. You strive to connect to what used to be, but trauma has created a fractured world. You live a second life. As you pour your morning coffee, you’re still trying to escape from harm or understand what has happened. Your body tenses. You’re ready to fight. Or run.

Our brains are wired for connection, but trauma rewires them for protection, as the saying goes.

The creative process gives permission to explore the unspoken.

I haven’t experienced true trauma, not the kind of trauma that wrecks and debilitates. But I have experienced moments of emotional pain and anxiety when I was unable to write. These moments might be better described as “creativity wounds.”

The first time I experienced this, it was at the hands of another writer, a renowned author who I took a writing class from. My hopes were ridiculously high. I wanted her to recognize my talent, to affirm my prose. I was young, and I walked into her class as if I was a puppy dog expecting to play.

When I turned in my story for her feedback, not only did she not recognize my talent, but she eviscerated my story. She might as well have used shears. “No shit!” she wrote in the margins of one page. I met with her in her office hours to ask her questions and hopefully make a connection, but she was equally cold and cutting, offering nothing that resembled constructive critique, just the pure vitriol of negativity.

She said my story was boring and pretentious. She said my dialogue, which others had previously praised, was limp and lifeless.

That was the first time in my writing life that I felt truly defeated. I was utterly unable to pick up a pen to write anything. I’d been critiqued in many a writing workshop before—severely even—so I wasn’t a naive innocent. But I’d never experienced such slashing and damning comments. I’d always been resilient and determined in the face of such negativity, but this time I lay on the couch watching TV for several days afterward, my brain looping through her scissoring comments again and again.

This must be a small version of what must happen with trauma: your thoughts dig into a painful loop as your brain tries to process the pain.

The act of naming

I heard a psychologist once say that unless we name trauma, we are powerless to transform it. It remains an antagonist, an enemy. The reason to try to write is that our creative urges help us explore, shape, and make sense of trauma.

Creating can feel counterintuitive, though. It can feel impossible to be creative in such intense moments, and you might not even be able to find the slightest impulse to put pen to paper.

A memoir instructor told me once that you have to be very careful with writing and trauma because sometimes the writing triggers the trauma, and sometimes a person needs to recuperate more before naming the trauma.

Wounds can open when least expected. Sometimes a wound never truly closes. You can stitch it closed, but the swelling puss within it can still break the stitches back open. It’s always vulnerable to infections, resistant to salves. Time heals . . . a little, but not necessarily entirely.

The question is how to begin again, how to recover the very meaning and joy that we found in our first stories—to recover the reason we write. The hope is that the process of writing will help open a doorway to a new world. When you create, you unconsciously look for openings. The creative process gives permission to explore the unspoken, to express with depth and abandonment.

I keep thinking of the group I talked with because I had so few answers for them. In the end, I didn’t give a speech. We talked of stories we’d written in the past. We talked of different writing challenges. We talked about our dogs and our kids and our favorite books. We ended up doing one short writing sprint.

I think they were dealing with their trauma in the right way. Making the world warm and nourishing again through the act of gathering. Letting their creative connections work in mystical ways.

A big part of the value of meeting was to simply maintain their belief in creativity. Somewhere within them, they trusted their stories would someday follow. Trauma can take away that trust, so we have to recreate it anew.

“Art is a wound turned into light."

—Georges Braque

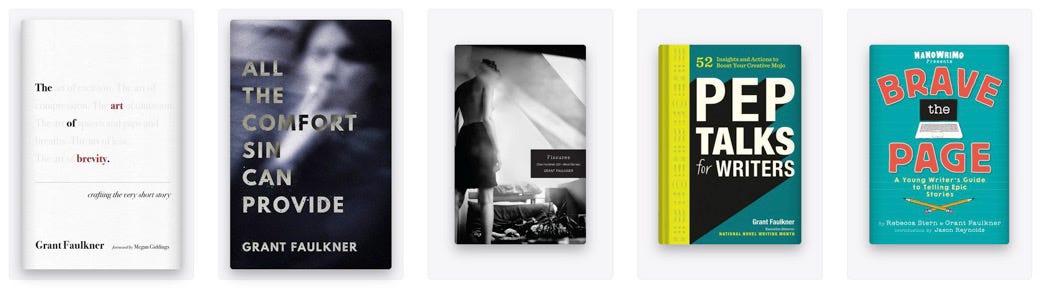

Because I’d love you to read one of my books

I write this newsletter for many reasons, but mainly just for the joy of being read and having conversations with readers. This newsletter is free, and I want it to always be free, so the best way to support my work is to buy my books or hire me to speak.

Hi Grant. Thank you for bringing attention to trauma and writing. Trauma is such a slippery, shapeshifting thing to me. It's invisible. It grows and then shrinks. It has a cycle. Some days are better than others. After about eight years after my dad died, I started tugging on the thread of where my grief came from and I discovered that I was born into grief as my mom was pregnant with me when her father was dying of cancer. And in fact she had me in the same hospital where he was being treated. I then went back centuries and found that I have a a 10x great grand mother who was killed during the Salem Witch Trials. Grief and trauma are like invisible participants in our lives. They can also change DNA. But as you recognized, the trauma needs to be acknowledged. And that might never happen in a person's lifetime and that's okay. My grief and trauma and pushing me in the direction of offering my experiences to others. I have been in the process of finding my voice and my words when I get into the background of my experiences. I want to offer my experience to others. Show that happy moments in the time after losing your intimate family members is possible. There is a lot to unpack. I went on a journey to find a system that would help me make sense of my life and what I found is the best system can be the one that someone creates for themselves. This particular thread led me to discovering not just one but two grad programs that can support my writing practice and help my words to be expressed.

The time we live in right now is quite interesting. There are people who are experiencing trauma and grief due to covid. My experience is comparable in that my parents both passed after illness but both were gone in the early 2010s (2010 for my mom and 2013 for my dad respectfully). I think right now I can be of assistance as people discover their 'new normal.'

Thank you for bring attention to writing and trauma. As a survivor, abuse affected almost every aspect of my life, especially my education. About 15 years ago, at age 55, I graduated college with a B.A. in writing. In my last semester, I wrote a short story for the class newsletter, which gave me the confidence that perhaps I could write one short story a month.

Each story built my confidence. A year after graduation, I applied for a Lanesboro Emerging Artist Residency Program, which offered a 4 week writing retreat. I was stunned by their response. They graded my writing, giving me a D-. That’s right. Not a D, but a D-. And the comment that burned into my brain was, “The only positive thing I can say about this writer is she can write a complete sentence.” I was insulted. Then I became angry.

I recognize I had much to learn about storytelling, and perhaps my storytelling was a C-. However grading it as if I was in grade school was unnecessary and the critique comment was unkind. Fortunately, I did not let it define me as a writer or stop me from writing. I spent the next 15 years honing my skills and I've finished my memoir. It is my hope that all such organizations will have a second set of eyes review comments before sending them out. Such harsh critiques could crush a budding writer.