Allow me to take you by the hand And tell you some simple And unforgettable things ... Because we were alone, Near the shore, under this canopy Of palms, and we loved each other, The pleasure was intense and Indescribable

These lines from the poem “Plage,” by Roland Chassagne, frame Edwidge Danticat’s new collection of essays, We’re Alone.

I was fortunate enough to recently have Edwidge on my podcast, Write-minded, and I’ve been thinking of “aloneness” and “togetherness” and the divide between the two ever since.

Edwidge also talked about how she writes with love, inspired by James Baldwin’s aim to do the same—and to be a witness with that love. I’ve had several writers on the show talk about how they write with a sensibility of love, so it’s been an ongoing question for me:

How does one write with love? How does writing with love change the words on the page? How does writing with love change the author?

Like everything having to do with love, it’s complicated. I don’t think the definiiton of love can be found in a dictionary. Each person’s definition of love is their definition alone. Love is defined when you’re together. But perhaps more important, it’s defined when you’re apart, when you’re alone. And perhaps the definition of love is an ongoing struggle (see the words of Carvell Wallace below).

Edwidge said she was taken by Chassagne because his words read like secrets.

“We’re alone is the persistent chorus of the deserted, as in no one is coming to save us. Yet, we’re alone can also be a promise writers make to their readers, a reminder of this singular intimacy between us. At least we’re alone together. Or as A. S. Byatt wrote in her 1990 novel Possession, ‘The writer wrote alone, and the reader read alone, and they were alone with each other.’”

Alone with each other. Life as a type of parallel play.

We are all deserted in different ways throughout life, and Edwidge weaves the theme of lost homes throughout her essays.1 I like that she focuses on the “singular intimacy” between the writer and reader, because that speaks to why I titled this newsletter Intimations—it’s my way of exploring and defining the intimacy I live for, which is akin to Edwidge’s.2

We might wake to hear the damning “persistent chorus” of our aloneness, but we reach out for solace—for love. For Edwidge, that means reaching out to her family, but not necessarily a family defined by blood. Edwidge expands the notion of family and how we’re constantly remaking our family, especially if you are an immigrant:

“Family is whoever is left when everyone else is gone. It is whoever is cleaning up at the end of the party or the funeral repast. It is that person whose one nod might comfort you more than hundreds of words from someone else. Family members help you carry your dreams and memories.”

Family is whoever is left when everyone else is gone.

This is the definition I take with me. Family = togetherness. But our family doesn’t happen to us—we make and remake our families. We are all a type of immigrant in the end, grouping and re-grouping, creating families, leaving families, finding families.

Intimacies on the page

It’s a little like the topic I wrote about last week, Visions Only Come to Prepared Spirts, about David Milch’s idea that writing should be “a going out in spirit”—a connection to the larger forces of life, not a burrowing into isolation or aloneness.

Writing with love then is writing with the purpose of a larger connection—and in service to a larger connection to form a singular intimacy. In fact, Edwidge devotes an essay to tell about her own “intimations” with authors like Audre Lorde and James Baldwin (my favorite writers are certainly loving family members).

Edwidge touches on her own “going out in spirit” when reading a course description with her daughter Mira of a writing class taught by Erica N. Caldwell.

“Imagine: ‘The Essay’ is a body of water—far-flung and teeming into the distance. And you, the writer, are alone on shore. Will you enter the water? And if so, how will you swim? Or will you stand on shore as the water splashes against your ankles?”

Edwidge ends the book riffing on this idea. She notes how she’s been lost, “but eventually, words, stories, find me” once she enters that body of water.

That’s the best we can do, right? Enter that body of water. Stop being alone on the shore. And try to stay afloat, trusting in our buoyancy, our ability to float with others.

What do you think writing with love means? Please tell me in the comments.

Listen to Edwidge Danticat on Write-minded

Preview: Carvell Wallace’s study of love

At the beginning of the year, one of my goals was to make this year a study of love. I made a reading list—bell hooks, Proust, Erich Fromm, Ocean Vuong, Annie Ernaux, and more—but I've been sidetracked by an infinite number of things, and then my reading has suffered in general this year.

But then I met the most amazing author and person, Carvell Wallace, on my podcast, and he just wrote this fascinating memoir: Another Word for Love.

He talked about love in such wonderful, nuanced, contradictory, provocative ways. Among other things, he defined love as a “struggle.” A personal struggle, but also a struggle with those who you love and who love you, a struggle to love better, a struggle to notice, to express, to be.

I have a hunch my study is going to be a lifelong project. I am re-starting it today.

Please contribute your spare change to help me publish this newsletter.

Because a quote or two

“One of the points of loving someone is to help them feel loved. That's actually, I think, might be one of the biggest points of it.”

“To return, to be made whole again. This is another word for love.”

—Carvell Wallace

I’m available for book coaching and editing!

I love working with writers, and I have some space on my Writing Consult calendar if you’re looking for help.

I help people develop books and projects from scratch and sometimes do larger edits on finished manuscripts.

Lately, I've worked on a few novels as well as some short story projects. I’ve also worked on helping people figure out what kind of writer they are or want to be, and which projects can help get them there.

Contact me to find out more about my one-on-one work with writers.

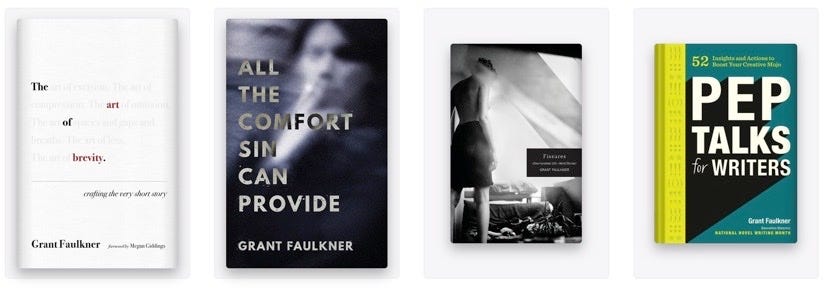

Because buy my books!

Because a photo

Oakland: the land of windmills …

In fact, Chassagne, a Haitian poet, was deserted by God, nation, justice, and humanity in a particularly horrific way. He was arrested at a Port-au-Prince publishing house for sharing “contraband literature,” and was then taken to François “Papa Doc” Duvalier’s notorious prison dungeon, Fort Dimanche, and was never heard from again.

See my post, Why “Intimations”? Why Intimacy?)

I wonder if writing from a place of love or with love in a memoir is holding another person's humanity in your words, even if they committed egregious acts.

I enjoy your thought-full messages. The idea of writing with, or from, love is intriguing and comforts me. I can do this! Perhaps I already do this (and didn't know I was writing from/with love). Something to ponder, especially "Edwidge expands the notion of family and how we’re constantly remaking our family . . ."